Déjà Review: this review was first published in September 2005 and the recording is still available.

Gioachino Rossini (1792-1868)

Guillaume Tell, Opera in four acts

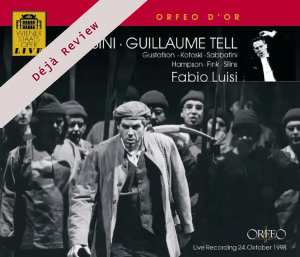

Guillaume Tell – Thomas Hampson (baritone); Arnold – Giuseppe Sabbatini (tenor); Walter Furst – Wojtek Smilek (bass); Melcthal – Walter Fink (tenor); Jemmy, Tell’s son – Dawn Kotoski (soprano); Gesler, Governor of the Cantons of Schwyz and Uri – Egils Silins (bass); Rodolphe – John Dickie (tenor); Mathilde, Princess of the House of Habsburg – Nancy Gustafson (soprano); Hedwige, Tell’s wife – Mihaela Ungureanu (soprano)

Chorus and Orchestra of the Wiener Staatsoper/Fabio Luisi

rec. live, 24 October 1998, Vienna, Austria

Orfeo C640053D [3 CDs: 192]

In the first years of his compositional life, 1811-1819, Rossini composed and presented a total of thirty operas. Like Bach, Haydn and others before him he re-cycled some music between these operas. He also wrote major revisions to several of them for different theatres providing happy endings to tragedies for example. It was a hectic creative pace. By comparison Rossini’s last ten operas were written over a more leisurely nine years with three of these works being major revisions in French of earlier Italian operas.

In 1828 when he began composing Guillaume Tell, Rossini was 36 years old and following the death of Beethoven he was the world’s best-known composer. It was his 39th and last opera despite his living until his 76th year. As Director of the Paris Théâtre Italien Rossini had a guaranteed annuity for life. In addition to this basic financial security he had earned considerable sums at the 1822 Vienna Rossini Festival presented by Domenico Barbaja, the impresario who had originally invited the composer to Naples and who presented six of his operas between February and July. On his visit to London the following year Rossini himself presented eight of his operas and sang duets with the king. His marriage to his long-term mistress, Isabella Colbran, also brought a considerable dowry after she inherited property. With good counsel from banker friends Rossini had enough money to live in style. Many have speculated that given his liking for social activities he saw no reason to continue the strained and hectic life he had perforce been leading. There was also the question of his mental resilience and physical state. Certainly his marriage was not successful and he and Colbran went their separate ways. In the 1830s his chronic gonorrhoea was a major health problem to him, exacerbated by frequent, and futile, stringent treatments.

Whilst Rossini had hinted at possible retirement during the composition of Guillaume Tell the work shows no signs of waning musical creativity, or capacity and concern for detail. It is by far his longest opera, a complete performance lasting nearly four hours. He took excessive care over its libretto, casting and composition. The opera is based on Schiller’s last completed drama of 1804. Rossini’s first choice of librettist was Eugène Scribe (who had provided the text for his previous opera Le Comte Ory) who preferred other subjects. Rossini then turned to the academic Victor-Joseph Étienne, librettist of Spontini’s La Vestale, and who had transformed the libretto of the Naples opera Mose in Egitto (5th March 1818) into the French Moïse et Pharon premiered at the Paris Opéra on 26th March 1827. He presented Rossini with a four-act libretto of seven hundred verses! Appalled, Rossini then called on the youger Hippolyte-Louis-Florent Bis who reduced the work to more manageable proportions and re-wrote the critical second act. Finally Rossini asked Armand Marrast to recast the vital section at the end of act 2 where the representatives of the three Cantons assemble and agree to revolt against the tyranny of Governor Gesler (CD 2 tr. 8). This is a scene that draws from Rossini some of his most memorable music in an opera of much melodic and dramatic felicity.

Rossini was also worried about the cast. In Le Comte Ory the soprano Lare Cinti had had a considerable success as Countess Adele and the composer had her in mind when he wrote the role of Mathilde in Tell. But she was pregnant and the proposed substitute was booed in another production. The premiere of Tell was postponed and Rossini had even more time to put the finishing touches to the work, which opened at the Opéra on August 3rd 1829. The tessitura of the role of Arnold gave the scheduled tenor Nouritt difficulties and after the premiere he started to omit the great act 4 aria Asile héréditaire and its cabaletta (CD 3 tr. 9). Soon further reductions and mutilations were inflicted. Within a year it was presented in three abbreviated acts and then act 2 only was given as a curtain-raiser to ballet performances. An often reproduced anecdote relates how Rossini met the director of the Opéra on the street who told him they were going to perform act 2 of Tell that night, to which Rossini was supposed to have replied ‘What the whole of it?’

The opera was first presented in Italian translation at Lucca in 1831 and the San Carlo in Naples in 1833. On record the Italian version with Pavarotti and Mirella Freni under Chailly recorded in 1978 (Decca) has vied with en EMI recording of 1973 with Gedda and Caballé under Gardelli’s less frenetic baton. Both recordings are recommendable featuring as they do a full text and tenors with good upward extensions. Pavarotti who later had a disc entitled ‘King of the High Cs’ declined to make his La Scala debut as Arnold claiming it would ruin his voice. A tenor friend of James Joyce is quoted as reporting that the role of Arnold required 456 Gs, 93 A flats, 54 B flats, 15 Bs, 19Cs and 2 C sharps. I cannot vouch for the accuracy of that estimate but certainly the role demands an ability to rise up the stave with full tone and dramatic intensity on a regular basis.

In this performance Giuseppe Sabbatini’s tightly focused, but ever musical and tastefully phrased tenor, meets the demands of the high notes if not quite having the heft and robust tone the role ideally requires in its most dramatic moments. I would not wish to damn his performance with faint praise because his efforts are always musical, in good French, and deserve the applause of the appreciative audience. As his lover, Mathilde – who he decides to forsake after the murder of his father – Nancy Gustafson sings with light tone adequate variety of colour and plenty of expression, but without the lightness and flexibility that would convince me that hers is the voice Rossini had in mind for the role. She lacks the ideal legato to caress the phrases in her aria Sombre foret, desert triste (CD 2 tr. 3) but rises well to the expressive demands and tessitura of the following love duet with Arnold when she confesses her feelings for him and he departs to win fresh laurels on the field of battle. The arrival of Tell and Walter Furst leads to a great trio when they accuse Arnold of being a traitor to the cause of Swiss freedom and then reveal that Gesler has murdered his father (CD 2 tr. 7). This dramatic trio when Arnold realises his duty and joins the rebels is, together with the finale that follows (CD 2 tr. 8), the musical and dramatic crux of the opera. Rossini, with his keen and experienced sense of theatre, fully realised this and hence his particular concern about the dramatic tautness of the libretto at this point; his music matches the intensity of the prose. Few, if any, pages of opera match that level of dramatic intensity and melodic invention until Verdi’s Nabucco. No wonder Donizetti is reputed to have attributed the rest of Guillaume Tell to Rossini but act 2 to God!

Act 2 demands more dramatic singing from Tell himself than act 1. Thomas Hampson’s lyric baritone of earlier years had grown considerably, with his assaying of Verdi roles and the like whilst in Sois immobile et vers la terre he can still invest tenderness in a phrase as he prepares to split the apple on his son’s head (CD 3 tr. 7). If he has lost a little of his earlier flexibility it is more than compensated for in the weight of tone and heft he brings to the dramatic act 2 trio and the confrontation with Gesler (CD 3 trs. 4-6). His French, unlike some of the comprimario parts is idiomatic. As important as the soloists in this opera is the chorus. In his operas for Naples in particular, Rossini honed his ability to use the chorus as a central character in the drama. In Guillaume Tell that process reaches its full flowering musically and dramatically with much of the opera revolving round magnificent choral ensembles. Its apotheosis is to be found in the finale to act 2 (part of CD 2 tr. 8) when the chorus represent the men of the three Swiss Cantons, each characterised musically, are called together to plan the revolt. Philip Gossett, the renowned Rossini scholar, suggests (Masters of Italian Opera, The New Grove, 1983) that his is the greatest single scene Rossini ever wrote. The Vienna chorus are as vital and vibrant at this point as they are appropriate in expressing the pastoral mood of act 1.

From the opening cello chords of the famous overture (CD 1 tr. 1) to the opera’s climactic conclusion (including the storm music, a Rossini speciality, Tell’s killing of Gesler and the general rejoicing (CD 3 tr. 11), Fabio Luisi’s pacing ideally reflects the many facets of the work. Inevitably, in a live performance, applause intrudes to disturb the dramatic continuity, but it is not excessive. The recording gives prominence to the orchestra with the voices set slightly further back as one might experience a performance in the theatre as distinct from a studio recording. At 193 minutes it is missing around 40 minutes compared with the studio recordings of the complete work previously mentioned. But this must be seen in comparison with the Cetra recording of 1951, re-issued by Warner Fonit, of 166 minutes. That mono recording is graced by the mellifluous tone of Giuseppe Taddei as the eponymous hero.

The accompanying booklet gives a track-related synopsis and an essay on the opera with comments on the Vienna production, the first in French for the famous theatre. I enjoyed the fluency and vibrancy of this live performance without the distractions of Davis Pountney’s typically quirky production and sets. It might be abbreviated, but what remains is blended into a cohesive and meaningful dramatic whole, which is more than can be said for some of the butchering the work received in Rossini’s lifetime. Well worth investigating.

Robert J Farr

Buying this recording via a link below generates revenue for MWI, which helps the site remain free