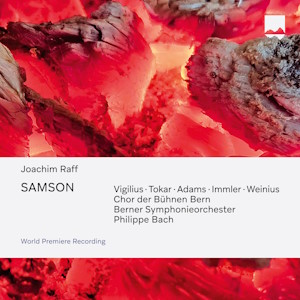

Joachim Raff (1822-1882)

Samson (1858)

Magnus Vigilius (tenor) – Samson

Olena Tokar (soprano) – Delilah

Robin Adams (baritone) – Abimelech

Christian Immler (bass-baritone) – Oberpriester

Michael Weinius (tenor) – Micha

Marjam Fässler (mezzo-soprano) – Oberpriesterin

Christian Valle (bass) – Von Askalon

Bareon Hong (tenor) – A Prison Guard

Katharina Willi (soprano) – A woman of the people

Choir of Bühnen Bern

Bern Symphony Orchestra/Philippe Bach

rec. 2023, Stadttheater Bern, Switzerland

Full libretto in German, French and English and Notes

Schweizer Fonogramm SF0016 [3 CDs: 184]

Lohengrin was premiered in 1850 in a performance conducted by Liszt whose assistant, Joachim Raff, then thirty, had only recently joined him in Weimar. Raff’s opera König Alfred appeared the following year, and was successfully received, and he soon began work on Samsom which he designated a Musikdrama along Wagnerian lines established by Lohengrin but from which Raff chose to diverge by introducing stylistic elements rooted in French Grand Opéra – Meyerbeer being the clear precedent. The complexities of this big, bold five-act work were not resolved until 1858 and then there was no production as, after the successful Weimar appearance of Saint-Saëns’ Samson et Delilah, Raff definitively dropped his own work. The première was given only in 2022, the bicentenary of Raff’s birth, in Weimar – appropriately, historically – and was then given its Swiss première the following year. This set is the result, a thoroughly prepared and outstandingly well documented box consisting of three CDs and two extensive booklets, one of 128 pages and the libretto of 136 pages, both in German, English and French.

Raff prided himself on historical accuracy and clearly went into some detail in his research for the project. The libretto is his own and the themes of the opera are those of a conciliatory conqueror undone by his generosity, reflected in his adoption of local custom and costume, his all-consuming love for Delilah and his eventual martyrdom, which is couched in a passion narrative. Contemporary political questions must also clearly have informed elements of the work.

Each act has its own strong sense of characterisation. Act I enshrines Samson’s victory over the Philistines and is full of scenes of carnage and battle, punctuated by triumphal March themes – Marches operate throughout as a kind of unifying device in the opera in one form or another – all of which Raff conveys in fluid form, finely orchestrated and powerfully conceived theatrically. Wagnerian declamation is paramount though Raff cannily ensures that each character has more conventional arias or aria-like elements. The Chorus has a notable burden in this act. Act 2 focuses on Abimelech, father of Delilah, torn between revenge on Samson and love for his daughter – and his long soliloquy offers an interior reflection after the blood and guts of the first act. Ensuing scenes give Micha, Samson’s nemesis, the opportunity to advance the case for Samson’s murder and the High Priest declares that Abimelech’s ‘mild heart does not serve us’. Raff means us to understand that, politically speaking, both Samson and Abimelech are ‘guilty’ of conciliation in the eyes of their respective people. The Third Act is given over to Samson and Delilah in a kind of extended love scene whilst the Fourth Act shows Samson’s betrayal and capture – much is brassy and militant. The final Act, with its series of choruses, is the inevitable cataclysm.

The casting conforms to prevailing orthodoxies. There’s a heroic tenor in the form of Magnus Vigilus’s Samson, commanding, even stentorian in the First Act, but increasingly lyric as the opera develops. Olena Tokar’s Delilah has to negotiate a trickier emotional trajectory, moving between love and shame, and increasing anger, at her father’s betrayal and does so finely. I understand that baritone Robin Adams, who sings the vital role of Abimelech, replaced the singer originally cast at a few days’ notice. If so, he does tremendously well, bringing a natural gravitas to his kingly role but also an increasing turbulence at the political manoeuvering in which he is forced to participate. Perhaps the best-known of the singers is Christian Immler, an intractable and adamantine High Priest. Michael Weinius is Micha, in love with Delilah and vengeful, whose tenor is well differentiated from that of Vigilus’ Samson.

Raff was a fluent and inventive orchestrator, within traditional bounds. Take a few examples; the final scene of Act II Scene II is sinuously full of harmonic foreboding. The vorspiel to Act III is translucent, a nocturnal graced with a violin solo, and in this act dappled winds and harp make their aural presence felt. Raff’s deft use of the harp at strategic points is noteworthy. The lightness of Raff’s orchestral sound world in Act V, in which Marches are now avuncular, not martial as before, is also cleverly characterised. There’s a section for a Dance of the Children in this final act, similarly drawing on his gift and facility for lighter music. There’s also a long cello solo – to balance the earlier one for violin – that sounds balletic.

And it’s here that the tension-and-release that Raff has built up and successfully sustained tends to drain away. His preoccupation to extend the work’s theatrical drama toward French models with extended dances and balletic flim-flam, comes fatally unstuck in this final Act. Its profusion of choruses, dances, and orchestral solos drains tension from the music and the plot-spinning undermines the dramatic action. Samson’s final Lohengrin-like declamatory aria prefaces a brief, hurried temple-destroying act of martyrdom but by this time it’s too late to recalibrate the action. Perhaps if the work had been staged in Raff’s lifetime he might have reconsidered this final act or perhaps he believed it worked contextually.

In any case, the opera has been splendidly served by the excellent Choir of Bühnen Bern and Bern Symphony Orchestra under the galvanising baton of Philippe Bach in this première recording. Solid preparation – notwithstanding that late cast withdrawal – has ensured that the work has appeared, and can be appreciated, in the best possible light.

Jonathan Woolf

Availability: Schweizer Fonogramm