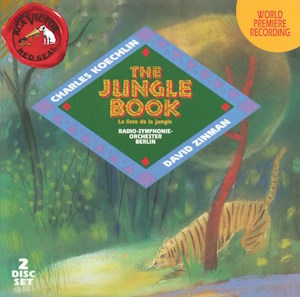

Charles Koechlin (1867-1950)

The Jungle Book

Three Poems, Op.18

The Spring Running, Op.95

The Meditation of Purun Bhagat, Op.159

The Law of the Jungle, Op.175

The Bandar-log, Op.176

Iris Vermilion (mezzo-soprano), Johan Botha (tenor), Rolf Lukas (bass), RIAS Chamber Choir

Berlin Radio Symphony Orchestra/David Zinman

rec. 1993, Studio 1, Sender Freies, Berlin, Germany

Presto CD

RCA 09026 619552 [2 CDs: 90]

When this recording was originally issued in 1994 the booklet note by Habakuk Traber was able to describe Koechlin as “the most neglected composer of his generation” who “today is being rediscovered.” But now this first complete recording of his works based on Kipling’s Jungle Book, which taken as a whole constitute “his central work, the concentrated summary of a long and creative life,” appears thirty years later somewhat in the aspect of a false dawn. No complete version of the Jungle Book has appeared to rival it; and the only competitor in the catalogues, comprising purely the four orchestral movements conducted by Leif Segerstam on Marco Polo, does not appear even to have materialised in what might have been expected as a Naxos reissue. An alternative recording under Heinz Holliger on SWR’s own label only furnishes the orchestral movements as part of a complete seven-CD survey of the composer’s music, and similarly omits the vocal settings.

But for those who have any interest in early twentieth-century French music this issue is quite indispensable. To begin with, the first of the Three Poems, the Seal lullaby from Kipling’s The white seal, is surely one of the most beautiful efflorescences of the impressionist era, a ravishing setting for mezzo-soprano and chorus which has a Delian richness of sound in its evocation of the sea wash. The story itself, far removed from the jungle setting of the main body of the stories, seems to have been a particular inspiration to composers; it also engendered one of Percy Grainger’s most atmospheric settings. It is beautifully sung here by Iris Vermilion, and the choir bring all the sensuousness of Debussy’s Sirènes to their soaring counterpoints. The other two songs in the set are less impressive; the Night Song in the Jungle is somewhat insistent in its rhythms despite the advocacy of Rolf Lukas who leads the ensemble (which may well be Kipling’s fault). And the exciting Song of Kala Nag suffers from being written with an extravagance of orchestral volume that aptly depicts the passion of the tame elephant’s longing for his wild existence, but leaves the singer struggling to be heard at all. The part is here assigned to the vibrantly heroic Johan Botha, who was to go on to an impressive career as a Wagnerian heldentenor (he died regrettably young, in 2016) but here sounds occasionally strained by the high tessitura.

Two of the purely orchestral movements here, The Law of the Jungle and The Meditation of Purun Bhagat, are both somewhat experimental works dealing with different approaches to mono-thematicism. The first, the shortest of the works in the cycle, revolves indeed almost entirely around one single theme without any contrapuntal accompaniment, taking its cue from Vincent d’Indy’s remarkable Istar where the composer took a set of variations and progressively stripped them of their elaborate raiment to leave a naked melody scored entirely for the orchestra in unison. Here Koechlin provides a similar experience, what the booklet note terms accurately as “an archaic, timeless power.” The longer Meditation takes a choral melody and expands it over a series of sparse sustained notes in the bass which finally culminate in a resolution which combines all twelve fifths piled on top of one another in a magnificent display of atonality with a purpose – and unexpected serenity.

Even more experimental is Les Bandar-log, the depiction of Kipling’s band of monkeys who try to imitate men but fail at their every attempt, which was the last of these pieces to be written and remains probably the best-known (it has been recorded several times in isolation since its première recording under Antal Doráti in the 1960s). This is a deliberately satirical piece which sets out to parody and ridicule elements in modern music with which the resolutely impressionistic Koechlin found his most profound disagreements: neo-classicism, jazz-like improvisation, and so on. It is only at the end that the serene sounds of the jungle finally impose calm. The problem with this is that Koechlin’s lack of sympathy with the styles he satirises makes it difficult for him the effectively parody the music of the composers with whom he takes issue – and his avoidance of any direct quotations from his ‘adversaries’ often makes it unclear exactly who he is taking the mickey out of, anyway. Perhaps it is best, listening to this music, to adopt the composer’s own slightly bland commentary: “The monkeys consider themselves inspired geniuses but are, after all, nothing more than self-satisfied mimics whose only goal it is to follow the fashion of the day…such things are said to occur in the world of artists, too.”

The earliest and longest of the symphonic poems, The spring running, is however an incontestable masterpiece. Founded on the last of the Mowgli stories to be found in the Kipling Jungle Books (where the second volume is generally deemed inferior to the first) this tale of the adolescent teenager growing to manhood and away from his friends in the forest is one of Kipling’s most heartfelt tales, tapping a reservoir of emotion that is too often denied him by his critics. It clearly struck a chord with Koechlin as well, where he combines in the course of four linked movements portraits of the natural world (the opening and closing Spring in the forest and Night) and depictions of the young Mowgli and his transition to adulthood.

It is perhaps a shame that this release does not present the orchestral movements in the order of Kipling, since The spring running clearly makes by far the most satisfactory conclusion to the cycle. But the presentation in order of composition has its own internal logic also, and the performances under David Zinman are superbly executed and beautifully recorded. The performances on Marco Polo under Segerstam are generally rather slower and grander in approach (not inappropriately so) but the orchestral playing of the Rheinland-Pfalz players is not as polished as that of the Berlin Radio forces here. Oddly enough Holliger with the Stuttgart Radio Symphony is even slower; but, as I have noted, these recordings come with a whole 7 CDs of other music some of which consists merely orchestrations by Koechlin of other composers. And in the final analysis the presence here of the three vocal and choral items, and most especially the Seal Lullaby, tips the balance decisively in favour of this RCA issue. If Naxos were perhaps to reissue the Marco Polo recording, that might prove a factor for the impecunious; but in the meantime this Presto reissue should be a compulsory purchase for anybody who loves French music of this period. As always in this series the transcription brings a complete reprint of the original booklet, including the French texts as set and Kipling’s English originals.

Paul Corfield Godfrey

Buying this recording via a link below generates revenue for MWI, which helps the site remain free