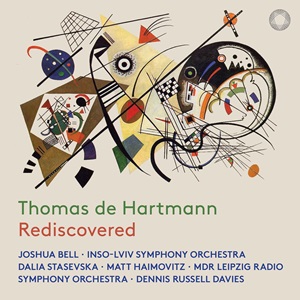

Thomas de Hartmann (1884-1956)

Rediscovered

Violin Concerto, Op 66 (1943)

Cello Concerto, Op 57 (1935)

Joshua Bell (violin)

Matt Haimovitz (cello)

INSO-Lviv Symphony Orchestra/Dalia Stasevska (Op 66)

MDR Leipzig Radio Symphony Orchestra/Dennis Russell Davies (Op 57)

rec. 2022, Gewandhaus, Großer Sall, Leipzig, Germany (Op 57); 2024, Warsaw Philharmonic Hall, Warsaw, Poland (Op 66)

Pentatone PTC 5187 076 [66]

The Ukrainian-born composer, Thomas de Hartmann, was a pupil of Arensky and Taneyev. The title of this album is ‘Rediscovered’, though as far as I’m concerned, it’s a case of ‘discovered’ because I don’t believe that I’ve encountered this composer’s music before. The album presents what I believe are the first recordings of two important concertos. Both date from the period, between the early 1920s and 1950, when de Hartmann was living in France.

The Cello Concerto was his first essay in the concerto form. I learned from the booklet that he was encouraged to write it by his friend Gérard Hekking (1879-1942), who was professor of cello at the Paris Conservatoire. The soloist here is the Israeli-born cellist Matt Haimovitz. I was intrigued to read in a short note by Haimovitz in the booklet that although de Hartmann was not Jewish, he was nonetheless “deeply affected by Jewish music and culture”. That certainly comes across in the concerto. The work, which is cast in three movements, is a substantial one; here, it plays for 35:17. The structure is weighted heavily in favour of the first movement, which occupies 20:45; this includes a couple of cadenzas for the soloist at either end of the movement. De Hartmann’s music is inventive and colourful, and I enjoyed it. I have to say, though, that so far, I’ve not found it easy to discern the trajectory of the music; I can’t help wondering if de Hartmann tried to pack too much in and, as a result, the movement ended up being a bit diffuse.

The slow movement is a very different matter, however. Marked Andante. Solenne, it’s a deeply serious and impressive creation. In his detailed notes, Evan A MacCarthy tells us that de Hartmann described the music as being like “the praying of the Jews, having endured everything except their God”. The movement begins with a lovely, extended cello song, gently accompanied. The music raises its voice only occasionally throughout the whole movement. I found it both beautiful and inspired. Haimovitz gives a dedicated performance, as does the orchestra; this performance is very moving. The finale is a rondo in 5/8 time. The music has a spring in its step, despite which the solo part includes a good deal of cantabile writing. It’s a most attractive conclusion to the concerto. Though I lack a comparative yardstick against which to judge it, the present performance seems to me to be excellent in every way.

However, the Violin Concerto is, I believe, a significantly more important work. De Hartmann dedicated it to another of his friends, the violinist Albert Bloch. Bloch had been supportive of de Hartmann’s music, but by the time the concerto came to be written, the violinist, who was Jewish, was in hiding in the south of France. Consequently, de Hartmann had to keep the dedication secret so as not to compromise Bloch’s safety; by the time the premiere took place in 1947, Bloch had died. Apparently, the composer himself described the work as “the Klezmer concerto” though so far, I’ve not discerned quite as pronounced a Jewish influence in the melodic material as was the case with the Cello Concerto. The key to this work is surely Evan A MacCarthy’s assertion that the concerto “mourns the destruction of Ukraine by war”. How timely, then, is this premiere recording, and all the more so since the orchestra is Ukrainian and the conductor, Dalia Stasevska, though resident in Finland since her childhood, was born in Kyiv.

The first of the four movements begins with a Largo section. Right from the start the listener can’t fail to notice the depth of emotion in both music and performance. Around 2:25 the soloist accelerates into the main Allegro section. This begins quite lightly, but it’s not long before the music becomes turbulent. Some of the music in this movement is fast and wild, but there are also some passages of great beauty, such as the lovely, tranquil episode from 6:00. The movement achieves a brief but intense climax just before 10:00 after which the soloist leads a gorgeously lyrical and quiet coda, which incorporates a short cadenza. I think this movement is gripping.

The second movement, Andante, features a good deal of yearning playing from Joshua Bell. For the most part, the orchestral contribution is quite restrained. The music is beautiful; it is by turns impassioned or lyrical. The last couple of minutes are magically hushed. De Hartmann entitles the very brief third movement Menuet fantasque. Only the soloist and muted strings are involved; the soloist plays throughout, tracing what the notes describe as an “ambling melody”. Apparently, the movement lasts for just 23 bars. De Hartmann wraps up his concerto with a finale marked Vivace. Here, the music is consistently dynamic and energetic; it often has the character of a folk dance. In this movement the soloist is given ample opportunity to display virtuosity and the orchestration is colourful and exciting. If, indeed, the composer was lamenting the wartime destruction of his homeland in the concerto then perhaps this last movement is his way of celebrating happier times, with a hope that they might one day return.

Thomas de Hartmann’s Violin Concerto is an impressive, eloquent work. Joshua Bell has clearly taken the work to his heart – that is evident not just from his playing, but also from some comments that he has contributed to the booklet. He is a commanding soloist. He receives superb support from the musicians of the INSO-Lviv Symphony Orchestra, incisively conducted by Dalia Stasevska. All the musicians bring out the power, poetry and virtuosity of the concerto. I enjoyed and admired the Cello Concerto, but I count the Violin Concerto as even more of a major discovery.

As I’ve come to expect with Pentatone, the recorded sound is very good indeed. Two separate production teams were involved; both have done excellent work. The booklet essays by Evan A MacCarthy, which cover the music and also the composer’s biography, are full of interest and valuable information. This disc has whetted my appetite to hear more of de Hartmann’s music.

This is a release that needs no special pleading whatsoever. However, as I was finalising the writing of this review I did a bit of online research, just to make sure I’d missed nothing significant. There, I found an article written in January 2024 for The Guardian by Charlotte Higgins, who had attended the sessions for the Violin Concerto. It is well worth reading. It will be noted that the Ukrainian orchestra had to travel to Warsaw in order to make this recording in safety. Ms Higgins records that the previous day the musicians queued at the Polish border for nine hours to get across. She also adds the poignant information that one of the orchestra’s horn players is missing in action. Despite all these hardships, the members of the INSO-Lviv Symphony Orchestra continue to make music with determination and, as this recording demonstrates, with undiminished skill. We must hope that it won’t be too long before they and their country will once again know peace – and proper security.

Buying this recording via a link below generates revenue for MWI and helps us keep free access to the site