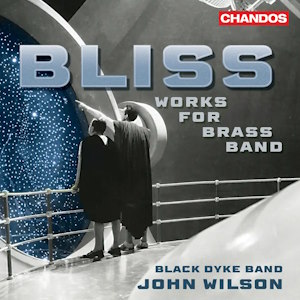

Sir Arthur Bliss (1891-1975)

Works for Brass Band

Welcome the Queen F.95 (1954, arr. 2023 by Micheal Halstenson)

Kenilworth – Suite for Brass F.13 (1936)

Suite from Adam Zero F.1 (1946, arr. 2023 by Dr. Robert Childs)

Things to Come Suite F.131 (arr. 2016 by Phillip Littlemore)

The Belmont Variations F.10 (1962, arr. Frank Wright)

Music from ‘The Royal Palaces’ F.128 (1966, arr. 2023 by Micheal Halstenson)

Four Dances from Checkmate F.2 (1937, arr. 1978 by Eric Ball)

Black Dyke Band/John Wilson

rec. 2024, Dewsbury Town Hall, Dewsbury, UK

Chandos CHSA5344 SACD [70]

In 1953 when Arnold Bax, the ill and ill-suited Master of the Queen’s Music died, Arthur Bliss was his astute replacement. Astute because not only was Bliss musically aligned with the requirements of the post but he had the administrative and personal skills to boot. Listening to this excellent new survey of works for Brass Band, you are reminded all over again what a skilled, attractive and memorable composer Bliss was. Yet despite the sterling efforts of labels such as Chandos, somehow that quality and attractiveness has not translated into wider familiarity, let alone popularity. Over the years, there has been a steady trickle of fine new discs covering the bulk of Bliss’ output – so by that measure the collector cannot complain – but somehow the perception remains that his music is a “specialist” interest. Perhaps much the same can be said of Brass Band recordings and again Chandos has been exemplary in its promotion of the finest bands playing the best repertoire superbly recorded. Indeed, go back roughly forty years and you will find the only two ‘original’ Bliss works for band featuring in genuinely excellent performances with one – Kenilworth – on a disc titled “Life Divine” featuring the same band, same venue and same engineer (Ralph Couzens) as this new disc.

Mentioning “original” works points up the single potential issue for some collectors. Of the 69:51 running time, less than twenty minutes are original with all the other works arrangements for band of orchestral scores. However, it is worth considering that the brass band movement started by playing exclusively arrangements of pre-existing music, so the versions offered here, several of which are brand new and listed as premiere recordings, are continuing a noble tradition. It is important, too, to reiterate – as I always do when reviewing Brass Band recordings – just how phenomenally high the technical and musical aspect of the playing here is. If you enjoy hearing instruments/ensembles played at the highest possible level regardless of genre, then listen to a top-notch band such as the Black Dyke Band here.

I was slightly surprised to see John Wilson conducting this programme – not that he does not do this well and of course British Music is an area of specialisation for him, but Black Dyke are usually recorded – to great effect – under their Musical Director Nick Childs and I am not sure what additional insights Wilson brings to this repertoire. As mentioned, the playing and arranging are superb and idiomatic and the Chandos SACD sound very fine. That said, I was genuinely a little surprised to find that I preferred the 1985 sound achieved in Dewsbury Town Hall in standard red book CD format to this new version. The 2024 recording is very accurate and detailed, quite neutral in some ways whereas in 1985 (obviously Kenilworth is the only work I can directly compare) the sound is a touch more immediate, with a greater weight and bite. Performance-wise they are both quite similar although the older recording is a handful of seconds longer in the first two movements. This is a tremendous work – compact yet varied – and as much fun to play as it is to listen to, I imagine. This is quite an early work – 1936 – but it already shows Bliss flexing those musical muscles that would serve him so well in his Master of the Queen’s Music role. He manages to take some of the heroic, noble elements of Elgar’s writing and blend them with a more contemporary feeling for rhythms and flashingly brilliant harmony that suits brass so well. This is epitomised perfectly in the opening movement At the Castle Gates (very different from Sibelius’ string-laden, sky-at-night work of the same name!]). A quick look through the catalogue for alternative versions aside from the earlier Chandos recording produces few results. On Doyen there is a 2019 collection from the Brighouse and Rastrick Band coupling the Bliss original works with some excellent yet little known Howells original band works but I have not heard that – experience tells me Doyen recordings are usually superb. Other than that, there is an old Decca/Grimethorpe Colliery Band versions and little else besides – a surprisingly scant showing for such easily attractive music.

Possibly the only work here which feels slightly less successful than its orchestral original is the March – Welcome the Queen which opens the disc. This is solely because the warmer cornet sound of a band smooths away the tonal brilliance of Bliss’ fanfare-like writing in this march written for a film documenting the young Queen’s (1954) return from her first tour of the Commonwealth. Arranger Michael Halstenson has made a couple of judicious cuts that are practically seamless but even though Wilson’s tempo is near identical to Bliss’ own Decca recording with the LSO, the result is lighter both in tonal weight but also in expressive impact.

Following on from Kenilworth is another arrangement prepared especially for this disc: Robert Childs’ suite drawn from the ballet Adam Zero. The five chosen sections last 10:28 and are skilfully selected and represent roughly a quarter of the complete score. The technical brilliance of the band is given full scope here with Bliss’ demanding writing and complex rhythms played with easy brilliance. This is evident in the bustling brio of the Dance of Spring [track 6] which combines all the best features of Bliss’ exuberant style. Here, the brass band transcription is completely effective and I can imagine this proving very popular with bands – as long as they have the technique to bring it off! The arrangement of four sections from Bliss’ film score Things to Come was made by Phillip Littlemore back in 2016 but this is its first recording. Again, the contrasting choice of movements is made for maximum contrast and expressive range and works very well. Hence the most famous piece of any by Bliss – the March for this film is placed last after the section called Reconstruction (when Bliss recorded a selection he used this title) on this disc but more commonly Epilogue when the complete score or extended suite is performed. Black Dyke play with great power and intensity but simply cannot match the opulence of the full orchestral version underpinned by organ pedals so superbly caught by Sir Charles Groves and the RPO in his 1976 EMI/Warner recording. It is interesting to note that Wilson chooses for the March nigh on an identical tempo to Bliss’ own recording with the LSO. This gives the piece a kind of nervy uneasy energy alongside the swagger of being a very memorable theme and second subject. Aside from the quality of this version, it is again worth remembering that this was one of the first – and arguably still one of the very best – major British film scores. When Bliss wrote this in 1934 no other British composer had come anywhere near writing a film score of this scale and calibre.

The Belmont Variations of 1962 were written as the test piece for the 1963 National Brass Band Championships held at London’s Royal Albert Hall. To ensure that the work was suitably testing but practical Bliss had specialist brass arranger Frank Wright score the work. Written as a compact theme and six variations with finale that lasts just 11:05, this is another tremendous work given a performance here of great virtuosity allied to expressive sensitivity. The individual and collective demands are extreme – as befits a test work – but the playing here is tremendous – as it was on the earlier (1983 original LP release) Chandos disc – here part of a collection called “Showcase for Brass” played by Besses O’ Th’ Barn band. Again, the Chandos engineering from over four decades ago is simply superb. That version apart, aside from the 2019 Doyen recording mentioned above there has only been one other version and that was from the days of LP which again I simply do not understand given the appeal and interest. I would commend the earlier Chandos disc not just for its engineering but also the mixed composer programme is genuinely fine. However, for those who only require the Bliss score this new recording can be warmly recommended and enjoyed.

The Music from ‘The Royal Palaces’ is another brand new Phillip Halstenson arrangement of a suite of music Bliss wrote for a joint ITV/BBC television documentary series. Along with Welcome the Queen and the complete Things to Come, this brief five movement [8:55] suite appeared on the Bliss Volume of the Chandos series of “The Film Music of…” series conducted by Rumon Gamba. The opening two movements are quite light in spirit – especially the second The Ballroom in Buckingham Palace a lovely swirling waltz. Joust of the Knights in Armour gives Bliss another chance to exploit his skill at fanfare-like martial music. Brilliantly played though it is by Black Dyke, the extra brazen bite of the BBC PO brass has the edge. That said, these band arrangements are not meant to replace the originals but rather to sit alongside them. I must admit I had forgotten what an attractive score this was – fulfilling a function for sure but doing it with an easy aptness and skill.

The disc is completed by Four Dances from Checkmate – the 1937 ballet score that in its complete form remains one of my very favourite Bliss works and one that is still as brilliant when seen in its proper danced version as much as in the concert hall. Eric Ball’s 1978 arrangement sounds brutally hard but it is thrillingly performed here. I cannot imagine many dancers managing to keep up with John Wilson’s pressing tempi. Again, the four selections – 13:04 of a score that lasts around 53:00 – are cunningly chosen to give a good range of mood and style from the complete score. I enjoyed the way the “misticamente” of the penultimate Ceremony of the Red Bishops is swept away by the closing Finale: Checkmate – surely too fast as played here in dramatic terms but a thrilling virtuoso display for sure. Anyone familiar with the full work will know how the frail Red King (representing Love) is finally cornered by the implacable Black Queen (Death) and after a brief moment of resistance succumbs – it is Checkmate. This is a simply magnificent score – one of the finest of all British ballets bar none – and it receives a compelling performance here to conclude a rewarding survey of Bliss’ always enjoyable scores.

My frustration here has nothing to do with the music, recording or performances – indeed the very high quality of all three of those elements simply reinforces the inexplicable marginalisation of the genre and the composer by the wider listening public. Thank goodness that labels such as Chandos and ensembles such as Black Dyke Band and conductors such as John Wilson still promote this endlessly rewarding and impressive music.

Nick Barnard

Buying this recording via a link below generates revenue for MWI, which helps the site remain free