Déjà Review: this review was first published in September 2003 and the recording is still available.

Ludwig van Beethoven (1770-1827)

Symphony No 9 in D minor, Op. 124

The Consecration of the House Overture, Op. 124

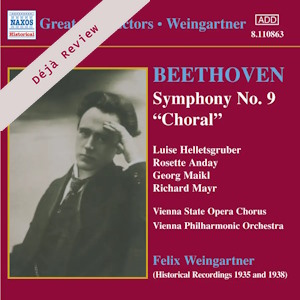

Luise Helletsgruber (soprano); Rosette Anday (contralto); Georg Maikl (tenor); Richard Mayr (bass)

Vienna State Opera Chorus

Vienna Philharmonic Orchestra, London Philharmonic Orchestra (overture)/Felix Weingartner

rec. 2-4 February 1935, Mittlerer Konzerthaussaal, Vienna; 7 October 1938, EMI Abbey Road Studio No. 1, London (overture)

Naxos 8.110863 [74]

With this release Naxos complete their series of the complete Beethoven symphonies under Felix Weingartner. After I had finished drafting this review I came across the review by my colleague, Jonathan Woolf of the penultimate release, which couples the Fifth and Sixth symphonies. He employs a most felicitous phrase, speaking of Weingartner’s “patrician imperturbability”. A little later in the same review he describes Weingartner’s Beethoven as “weighty but not weighed down.” Talk about phrases you wish you’d thought of first! These descriptions fitted to the proverbial tee my own response to this present account of the Ninth and, indeed, to the other volumes in the series which I have heard (ironically it is only that coupling of the Fifth and Sixth that has eluded me to date – but it’s on the shopping list!)

This Ninth was Weingartner’s second recording of the work. He had set down an earlier version in 1926. It was actually the fourth recording in what evolved into a complete cycle, having been preceded by the Sixth symphony in 1927, the Fifth in 1932 and the Fourth in 1933. I must confess I was nervous that the larger forces required for the ‘Choral’ might have defeated the engineers of the day. In the end those fears were not really justified. As producer Mark Obert-Thorn points out in a note, a completely different recorded balance was achieved for the choral section of the work (the final four sides of 78s) and we find the singers placed quite forward in the sound spectrum, especially the soloists, at the expense of the orchestra. However, I found that my ears adjusted fairly swiftly and I doubt any modern listeners will object too strongly at this artifice, especially since it’s the quality of the performance that counts.

Ian Julier, who has written the notes for all these Weingartner releases, and who is evidently (and understandably) an enthusiast writes thus of the present performance. .”Its special qualities offer a vivid experience in terms of interpretative values, the performing style of the time, and the art of comprehensively communicating the very essence of a masterpiece with a spontaneous sense of renewal and discovery.” I’d draw particular attention to that last phrase for my listening experience here convinces me that Julier is spot on in praising Weingartner’s communicative skill. It is his achievement to lay before us Beethoven’s great work without interposing himself between music and listener. This is, above all, a performance of integrity. It is also a performance of fidelity. I don’t necessarily mean by that that there are no deviations from the printed score. There are a number of tempo modifications (the first one as early as 3’50″ into the first movement and lasting for about a dozen bars.) As Julier points out, there are also one or two occasions where, to coin a phrase, Weingartner “sexes up” the instrumentation. No, what I mean by “fidelity” is fidelity to the composer’s intentions and in this respect I believe that the conductor scores 10 out of 10. This reading strikes me as experienced, thoughtful and logical. It is a reading to live with and no doubt that explains its longevity in the catalogue while many other recordings have come and gone.

The recorded sound in the first movement was the least pleasing, I found. This is, I think, because there are so many passages where the violins and/or the high winds play loudly and, as reproduced on my equipment at least, they often have a harsh shrillness. That said, I found that I adjusted to this and it did not spoil my enjoyment too much. On the other hand, the bass line is satisfyingly firm without ever being boomy. From the outset Weingartner displays a firm control of the symphonic argument and he manages a palpable sense of suspense. There is drive and purpose (though the music doesn’t sound hard driven) and I admire his ability, seemingly instinctive, to know when to screw up the tension. Similarly he knows when and where in the score to hold energy in reserve and when to release it to best effect.

The scherzo is fleet and lithe and is crisply played. The timpani, which are played with very hard sticks, register tellingly (thank goodness) and the horns and woodwind, the bassoons in particular, come over well, particularly when the dynamics are softer.

The sublime adagio starts off at a very broad and noble pace though later on the speeds become more flowing. The performance is deeply felt but never is there a hint of indulgence. The Vienna violins sing beautifully and there are also some fine wind solos. This reading is a long way removed from Furtwängler’s subjectivity and for once I think timings are instructive. Weingartner takes 14’47″ whereas Furtwängler requires 19’36″ for his celebrated live Bayreuth Festival account (EMI, 1951) and three years later in a live Lucerne performance (Tahra) his timing is almost identical. (Interestingly, two other comparisons taken from the shelves at random find Toscanini taking 14’21″ in his 1952 BMG studio reading while Klemperer live in 1957 (Testament) is closest of all to Weingartner at 14’44″). Personally, I find I can live with either approach though perhaps the very personal Furtwängler view is more for special occasions! As far as this present performance is concerned I find that Weingartner conveys a simple dignity though this is not to say for a moment that the reading is not searching. The pitching in the little horn solo at 8’25″ is a little “democratic” but this is a small blemish.

The finale, which, by the way, is sensibly split into seven tracks, gets off to a spirited start with the orchestral recits played quite quickly and with not too much rhetoric. They are true recits in Weingartner’s hands but the phrases are given sufficient room to breathe. I don’t have perfect pitch but I thought that when the trumpets enter to crown the statement of the big tune (track 5, 4’32″) they sounded somewhat sharp but the tuning settles down fairly soon.

The first entry of bass Richard Mayr is splendid. He has a big voice but his projection is very forward, which I like. His words are crystal clear and he hits every note in the centre (except when indulging in a little portamento.) As I said earlier, he is recorded well to the fore, as are all the soloists. In fact this is an excellent quartet in which Georg Maikl provides lusty ringing tone for his martial solo. The only point with which I would take issue is where, in pairs, they sing “Freude, Tochter aus Elysium” (track 10). Here, in their desire for an expressive legato they pull the tempo back quite markedly, the men especially. However, throughout their singing is dedicated and committed. The choral contribution is sterling though I did feel that sometimes the soprano line wilted a bit under the enormous demands placed on them by Beethoven. This was most noticeable in some of the long, loud notes up in the stratosphere.

Inevitably in such a big and well-known work listeners will find points of disagreement. However, I submit that this is a splendid, elevated achievement, a performance of inspiration that transcends occasional lapses of orchestral technique just as it transcends the inevitable sonic limitations. Indeed, it seems to me that Mark Obert-Thorn has done a first class job in making this sixty eight year old recording come to life again. Ian Julier’s notes are very good and the disc is filled out with a good account of the Consecration of the House overture, though I must say I feel this is one of Beethoven’s more workaday pieces.

I warmly welcome this release. Naxos have done a fine service in making this series of stimulating and enduring performances available to a wide audience. I have certainly found getting to know the Beethoven performances of Felix Weingartner an enriching experience.

John Quinn

Buying this recording via a link below generates revenue for MWI, which helps the site remain free