Sir Michael Tippett (1905-1998)

A Child of Our Time (1939-41)

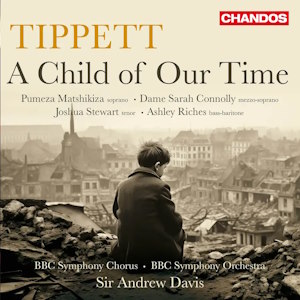

Pumeza Matshikiza (soprano); Dame Sarah Connolly (mezzo-soprano); Joshua Stewart (tenor); Ashley Riches (bass-baritone)

BBC Symphony Orchestra & Chorus/Sir Andrew Davis

rec. 2023, Phoenix Concert Hall, Fairfield Halls, Croydon, UK

Text included

Chandos CHSA5341 SACD [64]

I was lucky enough to see Andrew Davis conduct several times in his final decades, but it wasn’t in London, Chicago, or one of the other cities so closely associate with him: it was in Edinburgh. Towards the end of his life he developed a very close working relationship with the Royal Scottish National Orchestra and, by extension, with the Edinburgh Festival. I heard him in the Usher Hall conducting the RSNO in symphonies, oratorios, operas and more, and his visits became highlights of the year. Several times he was entrusted with the honour of closing the Edinburgh International Festival, and I’ll never forget a Walküre and Götterdämmerung that Davis and the RSNO did as part of an EIF complete Ring cycle.

As it happens, the very last concert I heard him conduct was A Child of Our Time in the 2023 Festival, with the RSNO and Dame Sarah Connolly, who also features on this disc. Tippett’s oratorio isn’t a work for which I have an enormous amount of affection – where others find universal spiritual insights and humane empathy, I find a clumsy level of cut-and-paste and an undue amount of taking his time – but I found Davis’ reading more moving than any I’ve heard in this piece before, and this recording serves both as a confirmation of that memory and a fitting memorial to the man.

In fact, Davis is both the guiding star and the prime mover of this Chandos recording. His understanding of the work’s overall scope surpasses even that of Tippett in his own recording, rendering superfluous most of my usual concerns about the work’s structure and shape. He has a clear line of vision that runs through all three parts of the piece and brings both narrative arc and dramatic purpose to it. That works for both the action and the music. Connections appear that might elude other conductors, and the whole structure appears to make more sense: things cohere so that the drama of Part 2 becomes more convincing than I’ve heard on any other recording, and the piece as a whole become more than just waiting for the next spiritual (something of which the composer’s own recording is often guilty).

Davis also manages to get his musicians to buy into this so that it feels very much like a team effort where everyone is pulling in the same direction. The chorus, for example, are clearly thrilled to be a part of Davis’ vision, if the way they act (as well as sing) is anything to go by. Their angry interjections cut through with dramatic edge and desperate power, but in the spirituals they can find touches of warmth and spiritual consolation that elude other choirs. The orchestral sound is beautifully put together, too, stabs of pain from the brass balanced by gentle, gorgeous softness from the strings, and there is a perceptible turning towards the light at the end of Part 3, which shows orchestra and conductor walking in perfect lockstep.

The soloists are excellent, too, both as individuals and as a team. Finest of them is soprano Pumeza Matshikiza, a huge voice, all honey and cream, but used with terrific sensitivity to evoke sympathy with suffering. Her interplay with the chorus during the spirituals is both sensual and profound. Sarah Connolly is very moving as the aunt, and bass Ashley Riches uses his voice to act as a cross between Old Testament prophet and universal watchman. Tenor Joshua Stewart is disarmingly moving when he first sings in Part 1, and he plays the child in Part 2 with a touching sense of doomed fatalism.

The Chandos recording is first rate, too, the sound of Fairfield Halls providing a warm, sympathetic shell for the piece’s varying sound worlds. The booklet contains the full texts (in English only) and a very perceptive essay by Mervyn Cooke.

I’m still not completely sold on it as a work of art: much of it still strikes me as high-minded mumbo jumbo with rather too high an opinion of itself, particularly in Part 3. I appreciate I’m in a minority on that front, though, and even I’m prepared to admit that this is the most convincing recording of it I’ve heard to date. And for that it’s Davis, more than Tippett, that we have to thank.

Simon Thompson

Previous review: John Quinn (July 2024)

Buying this recording via a link below generates revenue for MWI, which helps the site remain free