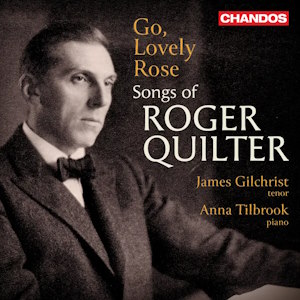

Roger Quilter (1877-1953)

Go, Lovely Rose

James Gilchrist (tenor)

Anna Tilbrook (piano)

rec.2023, Potton Hall, Dunwich, UK

Texts included

Chandos CHAN20322 [65]

Roger Quilter was essentially a miniaturist; he composed precious few pieces on any substantial scale, with the exception of A Children’s Overture (1914) and a light opera, Julia (1936), which he later revised as Love at the Inn (1940). Since he was a man with a deep and wide-ranging interest in literature, the composition of songs was his ideal métier. As Valerie Langfield observes in her excellent booklet essay, he composed some 150 songs. This selection of 27 items therefore represents about 18% of his output in the genre. It’s very good that James Gilchrist and Anna Tilbrook have chosen a number of less familiar songs to sit beside several, such as ‘Go, lovely rose’, that are well known. Quilter may not have probed as deeply in his songs as did, say, Finzi or Gurney, but, as the offerings here amply demonstrate, he understood his chosen texts very well indeed and had the knack of finding the right musical response to each poem; as Valerie Langfield very fairly points out “it was always the text that inspired him”.

It was instructive to read a short note by James Gilchrist in the booklet. He relates that his first ‘proper’ teacher (his choice of words) introduced him to Quilter through the medium of ‘Go, lovely rose’; that teacher, by the way, was Ena Partridge, the mother of another celebrated tenor, Ian Partridge. Gilchrist says this: “Theres something about Quilter’s music that feels true: it’s so beautifully crafted that it seems to flow as a part of nature; the music fits the text as if it’s always been there, the two inseparable; the sentiment and affinity with the poet feels unforced, to spring from a common humanity”. I fully agree with that comment, to which I’d add that the performances of both artists here demonstrate the beautiful craftsmanship of the music and, in Gilchrist’s case, the ideal fusion of words and music. Quilter’s songs suit all voice types but I think a tenor voice is especially good to hear in this repertoire, as we can experience here.

Rather than present one or more of Quilter’s song collections, Gilchrist and Tilbrook have very sensibly cherry-picked a number of songs which they’ve then put together in various groups. So, for example, they don’t perform the collection of eight songs to poems by Robert Herrick, To Julia, Op 8 but instead three of the songs are dotted around the programme.

They first offer a group of six Shakespeare settings. After the confident, outgoing ‘Blow, blow, though winter wind’ – an ideal opener – we encounter the melancholy side of Quilter in ‘Come away, death’. Gilchrist’s plangent voice is ideal for this song while the delicacy of Anna Tilbrook’s playing is a delight. Valerie Langfield justly observes that ‘Fear no more the heat o’ the sun’ is “thoughtful rather than raging”. Personally, I find Gerald Finzi’s response to these words goes deeper than Quilter ventures but the latter’s setting is still very fine; Gilchrist’s delivery of the last two stanzas is especially memorable. The group ends with a delicious account of the light and merry ‘Under the greenwood tree’.

The next group, A Floral Tribute, assembles five divers flower songs. I suspect ‘The Fuchsia Tree’ is not especially well known but it deserves to be, as this fine performance shows. By contrast, ‘Go, Lovely Rose’ is very familiar, and rightly so. As I mentioned, it’s the song that opened for James Gilchrist the door to Quilter’s art. He manages, though, to make it sound like a new discovery, even if it’s readily apparent that he and Anna Tilbrook know and understand every phrase intimately. That’s evident in the way they deploy rubato as they deliver this exquisite little song. ‘Now sleeps the Crimson Petal’ is another song that many will know. It thoroughly merits its popularity.

We move into folksongs for the next group. Quilter arranged no fewer than sixteen such songs over time and put them into a collection which he entitled The Arnold Book of Old Songs. Valerie Langfield explains the poignancy behind this title. Quilter had composed five such songs before his favourite nephew, Arnold Vivian went off to serve on the Second World War. Another eleven were written for Arnold to sing on his return but, tragically, he was killed in action in 1943; the collection thus became his epitaph. In the setting of ‘Barbara Allen’ there’s a more prominent piano part than is the case with the other three songs. However, Quilter has composed this in such a way that the piano adds interest without ever overwhelming the vocal line; in any case, Anna Tilbrook’s expert playing ensures that any such risk is avoided. In the case of ‘My Lady’s Garden’ and ‘The Ash Grove’ there’s added interest in that Quilter used the traditional melodies to set new words written by his friend, Rodney Bennett (1890-1948), the father of Richard Rodney Bennett.

A melancholy group follows; it’s entitled At the Graveside. Excellent though everything else on the disc has been in performance terms, I feel that these four songs particularly demonstrate the sensitivity and the perceptive approach of James Gilchrist and Anna Tilbrook. I’m not sure I’ve encountered ‘Dream Valley’ before but I’m glad I’ve now discovered it; it’s a lovely, gently sad song. Drooping Wings is just as fine; the song has sorrowful eloquence. It appears to be a standalone song in which Quilter set a poem by the Australian, Edith Sterling (1881-1971). Incidentally, it’s a tribute to how widely read Quiter was that he should have discovered not just this poem but also one by another Australian, Arthur Maquarie (1874-1955) whose words he set in the first song of this little group, ‘Autumn Evening’. If I were compelled to make a choice of just one Quilter song, I think it would be the exquisite little gem, ‘Music, when soft voices die’; so, I was delighted to find it included here. This short Shelley setting – it takes less than two minutes to perform – is perfectly crafted and wonderfully expressive. Gilchrist and Tilbrook give an ideal account of it.

The next group is something of a novelty: four German songs, which were previously unknown to me. I learned from the booklet that they owe their origins to the period from about 1896 to 1901 when Quilter studied in Frankfurt. Actually, despite their collective title, the poems were not the work of Mirza Schaffy but rather by Schaffy’s student, Friedrich von Bodenstedt (1819-1892). All four songs are simple in design and, to be honest, I can’t pretend they show the same level of accomplishment as the other songs on this CD. That said, they’re enjoyable and it’s valuable to hear them, not least because they flesh out our knowledge of Quilter’s career. The third of the songs, ‘Ich fühle deinen Odern’ (The magic of thy presence) seems to me particularly to presage Quilter’s future; Gilchrist sings it eloquently.

We’re back on familiar Quilter territory with the last group,Songs of Love. ‘Love’s Philosophy’ is a fine song. The rippling piano writing apparently caused Quilter a few difficulties when he played it, though he was an accomplished pianist. Needless to say, the music presents no problems to Anna Tilbrook; her effervescent playing admirably supports the rapturous vocal line. ‘Julia’s Hair’ is one of two songs in the group from the collection To Julia; there’s delicate eloquence in both music and performance. ‘It was a lover and his lass’ provides a light, cheerful conclusion, both to the group and to the programme as a whole.

This is a thoroughly enjoyable recital of Quiter’s songs. James Gilchrist and Anna Tilbrook seem completely attuned to the music and to the Quilter idiom. Furthermore, they’ve been regular recital partners for quite some time; it shows in the evident rapport between them. I hope very much that they may be persuaded to record another Quilter recital.

They have been ideally recorded by producer/engineer Jonathan Cooper who has achieved an excellent balance between voice and piano.

More, please.

John Quinn

Buying this recording via a link below generates revenue for MWI, which helps the site remain free

Contents

Shakespeare Songs

Blow, blow, though winter wind, from Three Shakespeare Songs (First Set) Op 6, No 3 (1905)

Come away, death, Op 6 No 1 from Three Shakespeare Songs (First Set) (1905, rev 1906)Fear no more the heat o’ the sun. from Five Shakespeare Songs (Second Set) Op.23 No 1

Orpheus with his lute. from Two Shakespeare Songs (Fourth Set) Op.32 No 1(1919-20)

O mistress mine, from Three Shakespeare Songs (First Set) Op 6 No 2 (1905, rev 1906)Under the greenwood tree, from Five Shakespeare Songs (Second Set) (1919)

A Floral Tribute

The Fuchsia Tree, Op.25 No.2 (1923)

Go, Lovely Rose, from Five English Love Lyrics Op.24 No.3 (1922)

A last year’s rose, Op 14 No.3 (1909-10)

Now sleeps the Crimson Petal, Op 3 No 2 91897)

To Daisies from To Julia, Op.8 No 3 (1905)

Folksongs

From The Arnold Book of Old Songs

Barbara Allen, No 13 (c 1921)

Drink to me only with thine eyes, No 1 (c 1921)

My Lady’s Garden, No 10 (c 1942)

The Ash Grove, No 16 (c 1942)

At the Graveside

Autumn Evening Op.14 No.1 (1909-10)

Dream Valley, from Three Songs of William Blake, Op.20 No.1 (1917)

Drooping Wings (1943)

Music, when soft voices die, from Six Songs, Op 25 No.5 (1926)

German Songs

Four Songs of Mirza Schaffy, Op 2 (bef. 1903, rev. 1911)

Songs of Love

Love’s Philosophy, from Three Songs, Op 3 No 1 (1905)

Julia’s Hair from To Julia Op 8, No 5 (1905)

The Maiden Blush from To Julia Op 8, No 2 (1905)

It was a lover and his lass, from Five Shakespeare Songs (Second Set), Op 23 No 3 (1919-21)