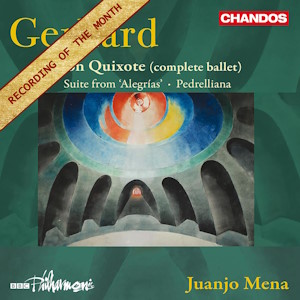

Roberto Gerhard (1896–1970)

Alegrías (1943)

Pedrelliana (En memoria) (1941; revised 1954)

Don Quixote (1941; second version 1949)

BBC Philharmonic/Juanjo Mena

rec. 2023, MediaCityUK, Salford, Manchester, England

Chandos CHAN20268 [61]

The fiftieth anniversary of Roberto Gerhard’s death came and went in 2020 with no significant acknowledgement of the milestone, an unhappy destiny ensured by COVID-19 lockdowns and endemic hostility from audiences, happily abetted by narrow-minded musicians and academics, to anything perceived as “difficult” or—heaven forfend!—atonal. Listeners who maintain that tonally untethered music is “cerebral” have obviously never heard Gerhard’s symphonies, some of the most blisteringly expressive in the genre. Those gentle souls driven to a fit of the vapours by the mere mention of the A-word, however, can safely put their smelling salts aside: the works on this Chandos disc antedate Gerhard’s belated embrace of his teacher Schoenberg’s methods. As Paul Griffiths’ fine liner notes point out, it is Stravinsky’s influence, rather than that of the magus of the Second Viennese School, that Gerhard subsumes here into his personal voice.

Gerhard, as man and artist, maintained an ambivalent relationship with his native Spain, a nation that shunned his compositions and forced him into exile, yet to which he returned regularly as a visitor. His bemusement and, perhaps in spite of himself, fascination with musical tropes that broadly characterize things “Spanish” to international audiences inform much of his output. These are especially apparent in Alegrías (Joys), the short ballet that leads this disc.

Its plot—about a young gypsy and the lecherous impresario she ultimately murders—is rife with grotesquely transmogrified flamenco and jota motifs that twitch about sarcastically. Suddenly, the fanfare from “La virgen de la Macarena” erupts to goad the music off course. Snatches of La boda de Luis Alonso juxtaposed against Chopin’s Funeral March follow suit, the whole manically whirling about until Gerhard finally dispatches it all straight to hell. If the recordings by the Louisville Orchestra and the Tenerife Symphony Orchestra, conducted respectively by Robert Whitney (reissued as a digital download on First Editions LOU-646) and Victor Pablo Pérez (Etcetera KTC1095), are marginally bolder in inflection, this new recording by the BBC Philharmonic conducted by Juanjo Mena has them both beat thanks to their superior playing and breadth of expression, not to mention the immersive Chandos production. These attributes are heard to especially winning effect in the “Preámbulo”, where its clashes of tone colours are balanced as delicately and playfully as I have ever heard.

Gamboling winds, held in check by timpani, in the Pedrelliana from 1954 evoke the Spanish Golden Age and Falla’s El retablo de maese Pedro. Modified and extracted from Gerhard’s 1941 symphony, Homenaje a Pedrell (which can be heard on Chandos CHAN 9693 played by the BBC Symphony Orchestra conducted by Matthias Bamert), the piece drops its veneer of friendliness soon after the introduction once orchestral layers, led by glockenspiel stings and snare drum rolls, start to pile on. As the pace turns harried, castanets stir the air, an ironic reference as much as to Gerhard’s hate/love of “españolete” stereotypes as to the rattling of bones and chattering of skulls. Merriment soon returns, albeit now undergirded by a disquieting ostinato played sul ponticello on the strings—have we been listening to a danse macabre for the Spanish Civil War dead all along? Gerhard seizes that question in mid-air and smashes it into the ground with a brutishly abrupt conclusion.

Among the central figures in the mythos around Spain’s “siglo de oro” is Cervantes’ hapless hidalgo, Don Quixote. Considering Gerhard’s complex relationship with Spanish culture and identity, his composition of Don Quixote, the concluding work on this disc and the longest, was practically foreordained.

Schoenberg’s serial procedures are idiosyncratically adapted here by Gerhard, but to ends more apparent to the eyes of musicologists following along with the score, than to the ear of the average listener. Unlike his teacher, Gerhard avoided expressionism in the first-person singular; the listener is permitted to observe the subject of this balletic psychodrama from a distance, but not to sympathize with him. The score’s kaleidoscopic orchestration—Gerhard was one of the 20th-century masters of the craft—gives plenty of opportunity for the BBC Philharmonic to really dig into this music. They make from it a precursor “concerto for orchestra” to the one that the composer actually wrote in 1965. Particularly enchanting is Gerhard’s use of percussion, with spiky keyboards and drums that alternately offset and mark the underlying pulse.

Dazzlingly colourful and rhythmically vivacious though the music is, it does not long conceal the Weltschmerz that pervades it. Tensions are not resolved so much as dissipated in the inscrutable “Epilogue”. Knight errant and composer finally gaze upon each other from across the centuries, their destinies threaded by the disenchantment of their respective worlds. As the music trails off into the void, it invites contemplation of the war and exile that marked Gerhard’s life, soon to be darkened further in his final years by the heart disease which eventually ended it.

Néstor Castiglione

Buying this recording via a link below generates revenue for MWI and helps us keep free access to the site