Déjà Review: this review was first published in August 2005 and the recording is still available.

Ludwig van Beethoven (1770-1827)

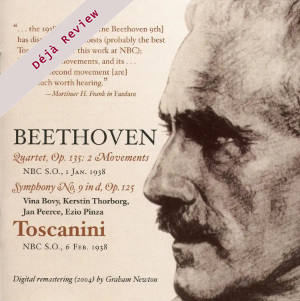

Symphony No. 9 in D minor, op. 125

Quartet in F, op. 135: Adagio/Lento, Scherzo

Vina Bovy (soprano), Kerstin Thorberg (mezzo), Jan Peerce (tenor), Ezio Pinza (bass)

Unidentified chorus

NBC Symphony Orchestra/Arturo Toscanini

rec. 6 February 1938, Carnegie Hall, New York

Music & Arts CD1135 [74]

Toscanini’s 1930s Beethoven seems to be arriving from all sides, and I must say this Music and Arts Ninth is a lot harsher on the ear than the Living Era transfer of the 1939 Third and Fifth which so much impressed me recently, with strident brass and seemingly little in the way of softer nuances. Maybe this has coloured my reaction, for I have to say the performance wasn’t quite the revelation I was hoping for.

It’s a while since I heard the “official” 1952 Ninth but Toscanini’s onslaught on the first movement has always remained in my mind as having a devastating impact on account of the rigour with which it is carried through. In the 1930s he was more flexible and we are always told this was a good thing. Unfortunately, the impression I get in the first movement was that sometimes he is not quite convinced himself with his fast speed and drops back, and then suddenly thinks this will never do and spurts ahead again. There are many impressive moments but also many where the music seems to be reduced to mere noise, an ironcast rhythmic outline being all that remains of it. Maybe if we could hear it better, it would be another tale. He also, very surprisingly, puts on the brakes as the 32nd-note passage in the violins comes up – a piece of consideration for his players I neither expected nor welcomed.

The scherzo has been described as “demonic” and I’d agree with that, but one does get tired of being browbeaten unrelentingly for nearly thirteen minutes. There are performances of this movement where you begin to think what a lot of repeats it contains, but I never expected Toscanini’s to be one of them.

The basic tempo for the slow movement is not all that fast, and there is certainly plenty of expressive moulding, plus some soupy portamenti I didn’t expect from this source. Toscanini’s relentlessness shows here, however, in the way he won’t leave the music alone, with big expressive bulges creating an overheated, Mahlerian effect. It was interesting to read, in Christopher Dyment’s notes, which are very detailed and present the case for the defence, that Toscanini always conducted the change to E flat major “with his eyes closed, so intense was his vision of ‘bright lights, far, far away’”, and in this passage the pressure actually comes off and the music momentarily becomes very beautiful.

In the finale the basic tempo is not so very brisk – Furtwängler went faster in places – but how Toscanini’s rhythmic “pom-pom” makes parts of it sound like the village band playing Verdi! When the “joy” theme returns after the fugue it comes in at a very good tempo – so right that he evidently thought it was wrong and whips it up after a couple of bars. Then surprisingly, when the “joy” theme and the “alle Menschen” theme are combined he takes a good, steady tempo and keeps to it. Towards the end he is off again, and there are some surprising rallentandos into the slower “alle Menschen” statements. Having recently (with the Third and Fifth mentioned above) discovered myself to be a Toscanini man, I am left wondering if this symphony does not respond more to the Furtwängler approach. Furtwängler could make his forces sound truly “feuertrunken” in the finale; here they sound cowed into subjection.

The original length of the CD (74 minutes) was chosen to accommodate Beethoven’s 9th without a break, but with Toscanini there is room left for a fill-up, and maybe this provides the most valuable part of the present disc.

As it happens, the two quartet movements are much more warmly recorded. But even so, the Adagio/Lento shows Toscanini in a quite different light, patiently unfolding the great melodic span. Here he and Beethoven can be heard reaching humanity, and not teaching it, a bad habit to which both men were prone. Given the warmer sound, the scherzo avoids sounding obsessive, though here the transportation to a full orchestral body of strings blunts the effect.

As I have said, Christopher Dyment explains in some detail why he considers this to be the finest Toscanini Ninth among those preserved, and quotes several other authorities in his support. So it looks as if Toscanini in this work is not for me. Those interested are warned that the sound is frequently no help at all.

Christopher Howell

If you purchase this recording using a link below, it generates revenue for MWI and helps us maintain free access to the site