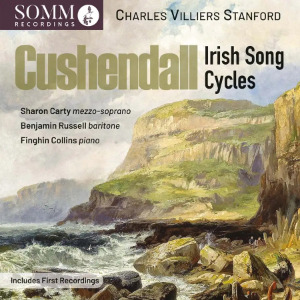

Sir Charles Villiers Stanford (1852-1924)

Irish Song Cycles

Cushendall, Op 118 (1910)

A Fire of Turf, Op 139 (1913)

A Sheaf of Songs from Leinster, Op 140 (1913)

Blarney Ballads

Two Songs from Shamus O’Brien, Op 61 (1896)

Sharon Carty (mezzo-soprano)

Benjamin Russell (baritone)

Finghin Collins (piano)

rec. 2023, The Menuhin Hall, Stoke d’Abernon, UK

Texts included

SOMM Recordings SOMMCD0681 [82]

Over the years, SOMM has done great service by Stanford, issuing amongst other things, his complete string quartets (review ~ review ~ review) and quintets (review) in excellent performances by the Dante Quartet), and also the opera The Travelling Companion (review). I’m not surprised, then, that the label has released this disc of some of his songs, performed by three Irish artists, in the year when we mark the centenary of Stanford’s death. It’s appropriate, too, that this release should focus on some of Stanford’s Irish songs because his roots in the island of Ireland were an important and consistent element in his compositional portfolio, including six Irish Rhapsodies for orchestra and his Irish symphony.

I’ve encountered the work of Sharon Carty before; she took part in a most interesting disc devoted to Stanford songs as orchestrated by the composer; I reviewed that disc recently. To the best of my recollection, I’ve not previously heard either baritone Benjamin Russell or pianist Finghin Collins.

In my review of the aforementioned disc of Stanford’s orchestrated songs I wondered whether the contents of that CD represented all of his song orchestrations or just a selection. I suspected that the disc was not a complete edition and the booklet of this SOMM disc proves the point. The essay on the music is by the Stanford expert Jeremy Dibble and I spotted very quickly the information that Stanford orchestrated the cycle Cushendall just a matter of months after he had completed the piano version. I don’t know if any of the remaining songs on this programme were also orchestrated by their composer though, of course, the two extracts from the opera Shamus O’Brien were conceived in orchestral dress; the complete opera has recently been recorded (review).

The cycle Cushendall, takes its name from a seaside town on the Antrim cost in Northern Ireland. There are seven songs, all of them settings of poems from a substantial collection by John Stevenson (1761-1833). I confess I’d never heard of this poet but I learned from Jeremy Dibble’s notes that he was a partner in an Ulster printing firm; he wrote under the pen name Pat McCarty. The poems, which Dibble says were “designed to be an exploration of the Irish way of life in the six counties of Northern Ireland”, do not seem, at least on the evidence of the texts that Stanford selected, to be particularly distinguished. The music to which Stanford set them is typically well-crafted but, like the poems, rather variable. So, for example, the first song, ‘Ireland’, is in what Dibble aptly describes as “simple, synthetic folksong language”; I fear it sounds rather too comfortable. The third song is ‘Cushendall’ and here we find a much more satisfying musical response. Stanford’s settling is rather lovely; the tempo is slow and the mood reflective. Stevenson’s words are a nostalgic evocation of a beloved place (‘The exile loves ye, Cushendall’) and Stanford’s music is an ideal response. The cycle also includes ‘The Crow’, a sarcastic comparison of the bird with sly lawyers, and ‘Daddy-Long-Legs’. The latter is a most unusual subject for a song but the staccato piano writing suggests the gawky tread of the multi-legged insect and the composer even throws in a witty, brief allusion to Wagner! Jeremy Dibble draws attention to the way in which, during ‘How Does The Wind Blow?’, Stanford imaginatively varies what is, essentially a strophic design. The last song ‘Night’ is as appealing as ‘Cushendall’ (to which there is a thematic cross-reference). ‘Night’ is a gentle and rather beautiful song which benefits from Stanford’s harmonic sophistication.

This, I believe, is the first recording of Cushendall. I mean no disrespect to the admirable pianism of Finghin Collins when I say that I’d also like to hear the cycle in its orchestral guise; that’s based on my recent experience of hearing the disc devoted to Stanford’s most imaginative orchestrations of some of his songs. Sharon Carty featured on that disc and here she’s entrusted with the recorded premiere of Cushendall. She sings the songs well and, as on the orchestral disc, I appreciated her clarity of tone and diction. I also noted more vocal warmth in these performances than I heard on the other disc. Having said that, I still feel there’s an insufficient range of vocal colours on display; the singing seems a little ‘samey’ to me. I’m sure not everyone will share that view and, as we shall see, there is better to come from her later in the programme.

Benjamin Russell takes centre stage for A Fire of Turf. This is a cycle of seven songs to poems by Winifred Letts (1882-1972). Letts was born in London and lived for at least part of her life in Ireland. Jeremy Dibble tells us that she was influenced by the Celtic Revival; that’s certainly apparent from her poetry. I’m afraid that quite a few of the poems which Stanford selected have not worn well. There has been at least one previous recording of this cycle; Stephen Varcoe and Clifford Benson included it on Vol 2 of a pair of excellent discs of Stanford songs which they made for Hyperion in 1990 (review). I liked Benjamin Russell’s singing very much. Hs voice is well focussed, firm, clear and evenly produced; there’s also a good variety of expression. The sheer sound of his voice is very pleasing and, like Sharon Carty, his diction is very clear.

Jeremy Dibble promotes the title song as “a broad, melodious elucidation, muscular yet gracious in sentiment”; it’s hard to quarrel, especially with the second half of that verdict. It’s well suited to Russell’s voice and Finghin Collins contributes an excellent, lively accompaniment. In some ways I’m tempted to pass over ‘The Chapel on the Hill’ because the poem is dreadfully sentimental; that would be unfair to Russell, though, because he sings it nicely. ‘Cowslip Time’ is, despite its twee title, an enthusiastic evocation of Spring. Later in the cycle comes its seasonal counterpart, ‘Blackberry Time’ which is merry and light-footed, especially as delivered by Russell and Collins. The final song in the cycle is ‘The West Wind’, which is the summation of the cycle. The music evokes very well the blustery winds so it’s a pleasing surprise when Stanford leaves the last word to the piano in a gentle postlude. There’s much to enjoy n this excellent performance of A Fire of Turf.

Sharon Carty returns for A Sheaf of Songs from Leinster. Once again, the chosen poet is Winifred Letts. Interestingly, though this set of songs was given the opus number following A Fire of Turf Jeremy Dibble tells us that Op 140 was completed first. Three of these songs – ‘A Soft Day’, ‘The Bold Unbiddable Child’ and ‘Irish Skies’ – were included in Vol 1 of the 1990 Hyperion collection by Stephen Varcoe and Clifford Benson (review); I’m pretty sure, though, that this is the first recording of the compete set – it’s not a cycle but, rather, a selection of Letts’ poems that Stanford wove together.

The first song, ‘Grandeur’ concerns quite an unusual subject: the wake of a dead Irish lady. The poem makes clear that in death she attracted more attention and respect than during her life as just ‘poor Jim Byrne’s wife’. It’s a strophic song, direct in expression. The following song, ‘Thief of the World’ is short and needs to be sung with a twinkle in the eye, which is just how Sharon Carty performs it. That’s followed by ‘A Soft Day’. I think this is one of Stanford’s most memorable songs; the setting is most economical of means but needs – and here receives – great concentration to bring it off well. ‘The Bold Unbiddable Child’ is another of Letts’ poems which has not worn well; it’s a patter song which Sharon Carty delivers in spirited fashion. The final song, though, ‘Irish Skies’ is in a different league. Here, the poet, living in London (as Letts may have been when she wrote the words), dreams of the Irish countryside. The words clearly struck a chord with Stanford and the resulting song has gentle eloquence. This fine song receives a touching performance.

Benjamin Russell returns for the three Blarney Ballads, which here receive their first recording. I can best describe these songs as a curiosity. They were written in response to one of William Ewart Gladstone’s failed attempts to pass an Irish Home Rule Bill through the British parliament, in either 1886 or 1893. Stanford was completely opposed to Gladstone’s initiative, as was his friend Charles Larcam Graves (1856-1944) who wrote the words. The three songs lampoon the British prime minister. My knowledge of nineteenth-century British politics is limited – as we historians like to say, when we need to cover our ignorance: ‘it’s not my period’ – and I’m afraid a lot of the topical references and allusions go over my head. The first of the three Ballads, ‘The Grand Ould Man’ (a reference to Gladstone himself) is ridiculously long: there are no less than 13 verses and the song quickly palls; the performance takes 7:00. I’m afraid I think Benjamin Russell miscalculates by delivering most of the words in a cod Irish accent, such as one might have encountered decades ago in an Ealing comedy. The second song, ‘The March of the Man of Hawarden’ alludes to the fact that Gladstone’s home was at Hawarden Castle. Seizing on the location of the said castle in Wales, Stanford employs the tune ‘Men of Harlech’ in his song. Happily, this time, Russell sings the song ‘straight’. The final Ballad is ‘The Wearing of the Blue’. Musically, this is the strongest of the three – it’s a low bar, though – and Russell characterises it well. I’ve listened to the Blarney Ballads dutifully for this review but I can’t imagine listening to them again. Whilst they have curiosity value, I can’t help but think there were better songs that Russell and Collins could have selected.

Finally, we hear Sharon Carty in two numbers from the opéra comique, Shamus O’Brien. Jeremy Dibble tells us that so great was the initial success of Shamus that several numbers were extracted and published separately with piano accompaniment. In my review of the recent recording of the complete opera I described the work as a whole as “something of a mixed bag”, though some of the set-piece solo numbers impressed me, including the two which SOMM have selected for this disc. Probably by sheer coincidence, I see that the SOMM sessions took place just a couple of days before the sessions for the compete opera. So, SOMM can claim the first recording of these two numbers – and, I’m sure, the premiere recordings of the piano versions. Both of the extracts come from Act I. ‘Where is the man that is comin’ to marry me?’ is a touching little number sung by the character of Kitty; she’s the sister of Nora, the wife of the opera’s eponymous hero. The other number, ‘A Grave Yawns Cold’ is rather more serious and eloquent. Nora sings of her apprehension that Shamus, who is on the run from the British authorities after a failed rebellion in Ireland, is in fact dead. The music is quite dark but it’s also attractively lyrical. I think Sharon Carty sings both of these items very well, especially Nora’s song.

The songs on this album are rather uneven but the best of them are well worth hearing. The performances are good. I have some reservations about Sharon Carty’s early contributions but she seems to grow into the music as the programme unfolds. Benjamin Russell is excellent. Both artists receive fine support from Finghin Collins. Engineer Oscar Torres and producer Siva Oke present the performers in good, clear sound which enables us to enjoy the music-making to the full.

SOMM’s documentation is up to the label’s usual high standard. The nicely designed booklet contains an authoritative essay by Stanford expert, Jeremy Dibble. All the texts are included and, praise be, SOMM present them (as they usually do) in a nice legible font.

Containing a number of recorded premieres, this is an attractive selection of some of Stanford’s many Irish songs.

John Quinn

Footnote

Since this review was published, Christopher Howell has informed me that there has been a previous complete recording of A Sheaf of Songs from Leinster. It was made by Bernadette Greevy with pianist Hugh Tinney. The recording was issued by Marco Polo and was welcomed by Christopher (review). I believe the disc remains available and since it also contains songs by other composers it complements this SOMM release nicely.

Previous review: Jonathan Woolf (March 2024)

If you purchase this recording using a link below, it generates revenue for MWI and helps us maintain free access to the site