Arvo Pärt (b. 1935)

De Profundis (1980/2008)

Dmitri Shostakovich (1906–1975)

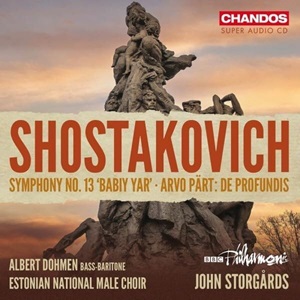

Symphony No 13, Op 113 ‘Babiy Yar’ (1962)

Albert Dohmen (bass-baritone)

Estonian National Male Choir

BBC Philharmonic / John Storgårds

rec. 2023, MediaCityUK, Salford, UK

Chandos CHSA 5335 SACD [70]

This is only the second release that I’ve heard in John Storgårds’ evolving Shostakovich series for Chandos: in 2020, I heard the Eleventh symphony, which I admired, albeit with some reservations (review). I was keen to see how the partnership would fare in the Thirteenth.

Early in 2024, I was presented with the opportunity to be a chorus member for two performances of Shostakovich’s Thirteenth symphony. I leaped at the chance because I consider this work to be one of the composer’s greatest achievements. Taking part in the rehearsals – to say nothing of the performances – and getting better acquainted with the score from the inside significantly strengthened my view of the work, even though it was a challenge at times to master the Russian words! This is a profound, searing work of great emotional depth. Subsequently, I read Jeremy Eichler’s compelling book, Time’s Echo. The Second World War, The Holocaust, and The Music of Remembrance. Eichler selected this symphony as one of four masterworks around which he constructed a moving work of historical and musical scholarship. I deepened both my knowledge and appreciation of Shostakovich’s symphony through reading what Eichler had to say about it.

To help me in learning the chorus part, I listened to several recordings in my collection. It was fascinating to compare and contrast these various recordings, some of which were more successful than others, but one emerged head and shoulders above the rest: Bernard Haitink’s superb Decca version with the Royal Concertgebouw Orchestra. That recording was made as long ago as 1984, but the Decca engineering still sounds mightily impressive, though the more recent BIS sonics for Mark Wigglesworth are outstanding (review). There is one other recording which, while very different from the Haitink – or, indeed, from any other modern recording made in the West – offers a special experience: Kirill Kondrashin’s 1967 studio recording for Melodiya (review).

Before I come to the symphony, though, I should consider the short work with which it’s coupled. De Profundis is a setting in Latin of Psalm 130 which Arvo Pärt composed for male voice choir, organ and percussion in 1980. Here, it’s performed in the later (2008) version, in which a chamber orchestra replaces the organ. The music is in Pärt’s ‘tintinnabuli’ style and, in essence, the music moves from a soft sepulchral opening through a gradual crescendo to a big climax from which the volume then recedes to the quiet of the beginning. As is so often the case with this composer, the music is characterised by extreme economy of means; the piece is akin to a hypnotic slow processional. I must admit that when I first received the disc, I was surprised at the coupling of a short piece that sets a Christian text with a huge and definitely secular symphony. On reflection, however, I came to feel that the coupling does work; the Pärt offers a sorrowful, ritualistic prelude to the symphony in which, inter alia, Yevgeny Yevtushenko and Shostakovich memorialised the slain of Babiy Yar. The connection is subtly emphasised because the last thing we hear at the end of this fine account of the Pärt is one soft chime on a tubular bell: at the very start (and end) of the symphony we hear a similar bell toll, albeit at a different pitch.

Shostakovich’s Thirteenth symphony courted controversy from the start. The Soviet authorities didn’t actually ban performances, but they placed significant difficulties in the way of the 1962 premiere, notwithstanding which the first performance went ahead and was well received. However, it was made clear to Yevtushenko that future performances would depend upon his willingness to make revisions to the text of the ‘Babiy Yar’ poem. Eventually, the poet conceded defeat, though Shostakovich disapproved. Tellingly, I believe that the score of the symphony containing Yevtushenko’s original text was not published in Russia until 2006. Shostakovich’s initial intention was to compose a standalone setting of ‘Babiy Yar’ but the project expanded into a symphony and four more poems were set. The poem which became the fourth movement, ‘Fears’ was written at Shostakovich’s specific request. It was the ‘Babiy Yar’ movement that caused all the trouble with the Soviet authorities. However, I think there’s a case for saying that ‘Fears’ is just as subversive; the difference is that in that poem Yevtushenko cleverly disguised criticism of oppressive government by suggesting this was something that had happened in Russia’s past; had the Soviet officials read between the lines they might have realised that the poem was holding up a mirror to the present.

The Thirteenth symphony is dominated in every way by the opening movement, a setting on a huge scale of the poem, which laments the terrible atrocities when thousands of Jews were murdered at Babiy Yar. When I first listened to this new recording, I wondered if Storgårds’ initial pace was just a fraction on the swift side. In fact, when I came to do some comparative listening, I found that his pace is comparable to both Wigglesworth and Kondrashin. Haitink is a tiny bit broader but somehow, he seems to convey greater breadth and tonal depth than the other conductors. The Estonian National Male Choir makes a very fine sound on the Chandos disc, as do the Netherlands Radio Choir (Wigglesworth). But the men of the Choir of the Concertgebouw Orchestra make a huge, imposing sound for Haitink; I have no idea of the sizes of the respective choirs, but Haitink’s choir gives the impression that it’s a very large body of men.

Storgårds’ soloist is the German bass-baritone, Albert Dohmen. He has an impressive pedigree; I read in the booklet that among his operatic roles are Gurnemanz, King Marke and Wotan. Most relevantly to the present recording, in 2021 he sang in a performance of the Thirteenth symphony, conducted by Thomas Sanderling, which was actually given in Babiy Yar under the auspices of the Babiy Yar Holocaust Memorial Centre. I’m in two minds about Dohmen. On the one hand, he sings the more thoughtful, reflective passages in this movement – and elsewhere in the symphony – very well and with a good deal of subtlety and expression. On the other hand, though, he doesn’t always demonstrate the heft and declamatory weight that we hear from some of his rivals. Dohmen sings quite calmly at first, but his performance grows in intensity as the movement unfolds. Haitink’s soloist is the Romanian bass, Marius Rinzler. He’s most imposing; when I reviewed the recording by Andris Nelsons, I wrote of Rinzler that “without any histrionics, [he] sounds as if he carries the weight of the world on his shoulders”. The Kondrashin recording presents us with something rather special, though. His choir is the Bass Group of the Russian State Choral Chapel; from them, we get the authentic, black Russian tone and, of course, they’re singing in their native tongue. So, too, is the bass soloist, Artur Eizen. He offers a Boris Godunov-like vocal presence and, like the choir, his enunciation of the words is the real deal. Overall, there’s much that impressed me in Storgårds’ account of the first movement, though the claims of rival conductors – and their soloists – can’t be overlooked.

The second movement, ‘Humour’ is the epitome of Shostakovich’s sardonic, satirical style. Yevtushenko’s poem portrays Humour as a character who is Till Eulenspiegel-like, but much more dark and subversive. Clearly, this struck a chord with the composer. Storgårds secures biting, incisive playing from the BBC Philharmonic and the choral singing is similarly acute. Dohmen does well, not least in bringing out the caustically witty side of the movement. Rinzler is very good indeed for Haitink but I think Haitink’s slightly steadier speed and weightier approach, the latter emphasised by the resonant acoustic of the Concertgebouw, robs the music of a bit of its edge. Kondrashin leads a biting performance: in particular, Eizen relishes every last syllable of the text.

The last three movements play without a break. ‘In the store’ is a bleak tribute to the daily grind of stoic Russian women who queue patiently in the freezing weather to make meagre purchases. As the poem progresses, it also becomes a reproach of those who undervalue the womens’ contribution to Russian society. The music, initially marked Adagio, has a glacial chill. I do wonder if Storgårds’ basic tempo flows just a fraction too easily. In the first few minutes, Dohmen’s delivery of the solo role conveys to me the sense of a compassionate observer – a completely defensible style, I hasten to add – though some of his peers seem more closely involved in the scene which Yevtushenko portrays. As in the first movement, however, his portrayal grows in intensity as Yevtushenko and Shostakovich wrack up the tension and the anger at the treatment of Russian women, who are so disregarded. Haitink’s performance has ominous depth – here the Concertgebouw acoustic does work in his favour once again – and Rinzler is sorrowful and very credible. Kondrashin offers a different perspective. His pacing is appreciably swifter, but the dark tone of his string players is potent. As for Eizen, the way he delivers the words suggests a ‘lived experience’ unlike any other soloist I’ve heard.

The fourth movement, ‘Fears’ follows without a break. The opening is quite remarkable; we hear sepulchral, quiet rumblings on bass drum and tam-tam and a baleful tuba solo. The word ominous doesn’t come close. Storgårds portrays this chilling, sinister opening very successfully. Dohmen is admirable; he is very credible and is ‘inside’ the text. The choir are equally effective, not least in the way they sing the ‘workers’ song’ episode, itself surely a parody. Haitink is superb in the opening pages; the cavernous acoustic really pays dividends here, adding to the sense of foreboding. Rinzler is eloquent and dramatic, and once again the Dutch choir delivers the goods. Kondrashin’s recording betrays its age here, not least because in the first passage they sing, his choir is too ‘present’. Eizen’s singing is searingly intense.

There are, in essence, two elements to the fifth movement, ‘Career’. One element is the almost innocent material which we first hear voiced by the flutes; much of the music which the orchestra plays by itself stems from this. The other is perky, sardonic music to which Shostakovich sets Yevtushenko’s satirical poem. All aspects of this movement are done very successfully by Storgårds and his musicians. I’m less convinced by Kondrashin here; though the singers do very well, the conductor’s swift tempo for the innocent material is unsatisfactory. Haitink is a touch too deliberate in this movement. I think Storgårds, gets it just right; the whole movement is a success in his hands. On balance, I think Storgårds gets the palm in this movement; the BBCPO plays the enigmatic ending with great finesse, leaving an excellent final impression of this performance.

The one question I haven’t yet discussed is the recorded sound of this new Chandos release. I listened to the stereo layer of the SACD. It’s a very good recording, as you’d expect. There’s an abundance of detail and plenty of impact. The choir and the soloist are very successfully balanced. That said, I’m not sure that the Chandos recording walks away with the gold medal. The Wigglesworth recording on BIS – again I listened to the stereo layer of the SACD – is superb, but in some ways the surprise package is the Haitink. I say ‘surprise’ because this recording is now 40 years old. The Decca engineers convey the stature of Haitink’s performance; there’s marvellous depth to the orchestral sound and the choir packs a real punch. As a comparative example, midway through the first movement (from about 9:15 in the Storgårds performance) there’s a huge, extended orchestral climax. It’s very impressive on the Chandos disc, but when I turned to both the BIS and Decca recordings, I experienced even better results. In particular, the percussion is presented more thrillingly on those recordings than even Chandos manage; Wigglesworth’s percussion section is explosive while Haitink, his orchestra and the Decca engineers offer a shattering experience. Of course, this is only one passage in the symphony. By and large, though, I think it’s a fair reflection of the sound quality throughout each recording: the BIS sonics are outstanding; the Decca sound wears its years lightly and makes the performance sound even more imposing, though the resonant acoustic tends to blunt the second movement a little; the Chandos sound is excellent and does full justice to the performance. It’s appropriate to say that the Kondrashin performance comes in sound which betrays the fact that it was recorded in 1967; the sound is not too sophisticated.

I should mention the documentation. Chandos offer a very useful set of notes by David Fanning. I have not, as I usually do, included “Texts included” in the header to this review because I don’t want readers to get the wrong impression. Pleasingly, the booklet includes the Latin text and English translation of De Profundis. However, for the symphony, Chandos provide only an English translation of the poems. I think that’s a mistake: unless you have some knowledge of what’s being sung, it’s not always straightforward to relate the English to what you’re hearing; ideally, Chandos should have provided a transliterated Russian text as well.

It’s time to sum up. I think there’s a great deal to admire in John Storgårds’ performance, though he hasn’t shaken my allegiance to Haitink. Storgårds conducts the work well and he’s excellently served by his choir and orchestra. Albert Dohmen sings intelligently and with a fine feeling for the words; he also observes a lot of the subtleties in the solo part. However, he’s a bass-baritone and I feel he lacks the sheer potency of a big bass voice; increasingly I’m of the view that this score needs an imposing genuine bass voice such as we hear on the Kondrashin or Haitink recordings. When my colleague Dominy Clements reviewed the Kondrashin recording, he said this: “The soloist, Artur Eizen, is powerful and eloquent, narrating as much as singing, giving the text what I can only describe as a biblical character – not hectoring, but emphatic and challenging.” I agree, though I’d add that Marius Rinzler comes close to matching Eizen. If you’re collecting the Storgårds series you’ll want this latest release and I don’t think you’ll be disappointed, but Haitink and Kondrashin, in their different ways, add an additional dimension to this searing masterpiece.

Previous review Néstor Castiglione (April 2024)

Buying this recording via a link below generates revenue for MWI and helps us keep free access to the site