Dmitri Shostakovich (1906-1975)

Symphony No. 13 in B flat minor, Op.113 “Babi Yar” (1962)

Arvo Pärt (b. 1935)

De profundis – Psalm 130 for male voices and chamber orchestra (2008)

Albert Dohmen (bass-baritone)

Estonian National Male Choir

BBC Philharmonic/John Storgårds

rec. 2023, MediaCity, Salford, Manchester, UK

Reviewed in surround sound

Chandos CHSA5335 SACD [70]

John Storgårds and the BBC Philharmonic began their Shostakovich symphony cycle at the end. Symphonies No. 11, 12, 14 and 15 appeared earlier. In No.13, he now reaches one of the greatest of them: the setting for male voices of poems by Yevgeny Yevtushenko (1932-2017). The symphony is one of the four key works which Jeremy Eichler discusses in his fine book Time’s Echo: The Second World War, The Holocaust, and the Music of Remembrance (Faber 2023). The others are Richard Strauss’s Metamorphosen, Benjamin Britten’s War Requiem and Arnold Schoenberg’s A Survivor from Warsaw (one might want to add Steve Reich’s Different Trains). Each is an answer to Theodor Adorno’s dictum about the impossibility of art after Auschwitz.

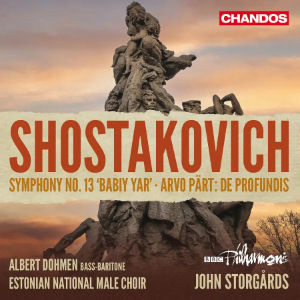

The Symphony begins with a poem already well-known in 1962: Babi Yar. It is the name of the ravine near Kyiv where an SS unit shot dead 33,771 Jews over two days in 1941. Yevtushenko visited the spot in 1961, and that night began his poem thus: “Above Babi Yar there are no memorials.” There is one now; its photograph appears on the CD cover. But the poem and Shostakovich’s setting are the best memorial. The Soviet authorities tried to ban its performance, and failing that to bowdlerise the text: it condemns the antisemitism not only of the Nazis but also of the Soviet regime.

Shostakovich first wanted to set this poem as a cantata, but then added Yevtushenko’s four poems to create a vocal symphony for bass soloist and bass choir (also referred to as male choir). My score specifies “basso coro (40-100)”, and such numbers of basses might well have been feasible in Russia in the 1960s. That did not stop a London Symphony Orchestra performance in April 2023; they listed nearly as many tenors as basses “on stage”. Yet the basses sing in unison almost all the time. It may matter little if there is predominantly low good choral sounds that respect the composer’s plainly monochrome intention.

The excellent Estonian National Male Choir is not as weighty as some. They number about forty-five in the booklet photograph, and they are probably not all basses. But they have an impressive sound, whether they sing loud or soft. The soloist Albert Dohmen, a celebrated Wotan among other roles, has a voice styled as “bass-baritone”, so a different colour and weight than the bass solo specified and usually heard in the Symphony. He sings well, with plenty of detail, a feeling for the text, and a degree of expressiveness for the harrowing themes of the poetry, if not quite as biting in the satire as some predecessors. His notes are always centred, with none of the vagueness of pitch of some basses with wider vibrato. Vocally, the soloist and choristers are reliable guides through the often politically provocative and thus dangerous poems. One is reminded of the Soviet-era jest: “Who are the most courageous people in the world? The Russians, because every fourth person is an informer and they still tell political jokes.” This is reflected in the second movement, a setting of the poem “Humour”, well brought off in this account.

Storgårds is generally a sure Shostakovich hand, to judge from reviews of his earlier recordings. His tempi feel right here. I checked them against some notable Russian conductors. The table shows quite a degree of unanimity over total timings. The two swifter recordings have mainly a shorter first movement, in any case the longest movement by quite a bit, with scope for quicker tempi in a few passages. Storgärds is at his best in the last three linked movements. He takes more flowing tempi than most in the slow third, to good effect, slower than most in the fourth movement, though it hangs fire only slightly as a result. The ironic finale “Career” is very nicely pointed, not least by Dohmen, and the BBC Philharmonic are as fine here as elsewhere. The opening flutes then the jaunty bassoon catch the mood, and the whole ensemble makes much of the work’s instrumental interludes. The closing bars from celesta and that final toll on the tubular bell set the seal on a very satisfying performance.

| Kondrashin 1967 | Rozhdest-vensky1985 | Maxim Shostakovich1995 | Polyansky1998 | Barshai2000 | Ashkenazy2007 | Storgärds2024 | |

| I | 13:43 | 16:43 | 16:47 | 16:36 | 17:09 | 14:20 | 16:07 |

| II | 8:09 | 8:02 | 8:26 | 7:51 | 8:28 | 7:49 | 8:31 |

| III | 10:48 | 13:54 | 12:53 | 13:08 | 12:44 | 10:22 | 12:00 |

| IV | 9:48 | 12:02 | 13:30 | 11:59 | 11:55 | 9:41 | 12:00 |

| V | 11:37 | 12:09 | 13:38 | 12:25 | 12:29 | 11:43 | 13:49 |

| 54:07 | 62:55 | 65:18 | 62:05 | 62:47 | 54:12 | 62:35 |

I personally could not live without Kondrashin’s recording, not the least because he premiered the work when Mravinsky and other more senior conductors fought shy of this political hot potato, as did a couple of the proposed bass soloists. He directed a triumphant first performance, and he triumphed again a few years later. At the first entry of the splendid Russian basses, the effect is such that we are transported to one of Shostakovich’s own reference points for his work, the world of Mussorgsky, reporting events of serious import for the State. The bass soloist, Artur Eizen, is involved and involving. This recording encapsulates the meaning of the work like no other, and even brings us something of the Soviet era in which it was made, in both the vocal and orchestral sound.

The issue I have is in the well-remastered complete Shostakovich Symphony cycle, which alas has no texts (Melodiya 2006, review). It has in fact later censored the text of the first poem, which might bother Russian speakers, or anyone following the original text of “Babi Yar”. For them, there is a 1962 recording (now on the Alto label) with the original text, by Kondrashin and bass Vitaly Gromadsky, who sang at the premiere. The sound is a bit more primitive, but quite acceptable given its historical importance.

Storgärds offers a very good modern choice, with a sophisticated Chandos SACD surround-sound recording and a striking bass drum presence. There also is a valuable coupling, in Arvo Part’s De profundis, whose bell and bass drum sounds benefit from the truthful recording as much as those in the main work. Its seven minutes make a very attractive and appropriate curtain-raiser to the main item. Perhaps the performance of the 13th Symphony burns at a slightly lower emotional temperature than some others, and than the poetry invites. But that might be just what has value for those listeners who are wary of the relentless high intensity of the Russian conductors listed above. Certainly those collecting this SACD cycle need not hesitate.

Roy Westbrook

Previous reviews: Néstor Castiglione (April 2024) ~ John Quinn (July 2024)

If you purchase this recording using a link below, it generates revenue for MWI and helps us maintain free access to the site