Serge Prokofiev (1891-1953)

Piano Concerto No 3 in C major, Op 26 *

Toccata, Op 11

Sergei Rachmaninov (1873-1943)

Piano Concerto No 1 in F-sharp minor, Op 1 *

Robert Schumann (1810-1856)

Variations on a Theme by Clara Wieck (“Quasi Variazioni”)

Felix Mendelssohn (1809-1847)

Song without Words, Op 62 No 1

Octavio Pinto (1890-1950)

Three Scenes from Childhood

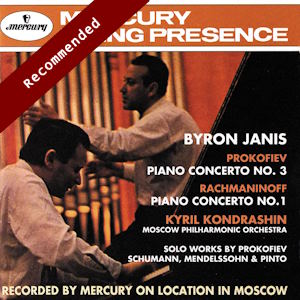

Byron Janis (piano)

Moscow Philharmonic Orchestra/Kyril Kondrashin *

rec. 1962, Bolshoi Hall, Moscow; 1964, Fine Recording Studio, New York (Schumann)

Presto CD

Mercury Living Presence 434 333-2 [70]

Ah, the magic words: “Mercury Living Presence”! What a stir they caused when the first such LP, recorded using a single microphone, burst on the scene back in 1951. But, why the stir? Well, almost from its inception (mid-1920s) electrical recording had used multiple microphones. At first, this was necessitated by the technical limitations of early microphones.

By the time that improving microphone technology had made multiplicity unnecessary, it had already become a somewhat ingrained habit. Robert Fine’s startlingly realistic “Living Presence” technique, involving only a single, broad-spectrum microphone fed directly into a tape recorder, effectively pulled the rug out from under the whole habitual setup (or, rather, it ought to have done so!). Within a couple of years, Fine was experimenting with a stereophonic equivalent – for details, including why Fine needed, not two but three mics., please refer to this article.

Whilst Fine’s three-microphone stereo configuration was, as we all know, capable of truly remarkable results, setting it up was – to say the least – a very tricky operation. Thus, for example, when recording Borodin’s Polovtsian Dances, it proved impossible to obtain a satisfactory balance between chorus and orchestra; this was resolved – by the rather extreme expedient of moving the entire chorus into the front stalls.

There is evidence of a similar technical difficulty in the recording of the two concertos on the Presto Classics disc here under review. Basically, the solo piano has a tendency to swamp the orchestra. Inevitably, the adjustments available are constrained by the “line of three” configuration. Listening to the recording, it sounds as though the piano is too far forward relative to the body of the orchestra. In the less closely-cropped cover images that I’ve found, this does look to be the case. Sadly, that oversight cannot be fixed by fiddling with the central mic. gain. Yet, if they could move an entire chorus, why didn’t they just move the piano back into the front of the strings? Happily, that little word “tendency” saves, if not the entire day, then at least the majority of it!

Of course, for these recordings the greatest challenges were not technical, but the unprecedented difficulties of even gaining access to the recording location – in Moscow, “back in the USSR”. Fully two of the 13 pages of booklet text are devoted to describing this historically significant but surrealistically convoluted carry-on. Thankfully, none of that is relevant here: once the musicians and recording engineers had at last come together, everything went splendidly. Indeed, by all accounts the orchestra and Janis were itching to play together again, whilst the Soviet engineers in attendance were mustard-keen to learn from the horses’ mouths about this intriguing recording technique.

In passing, one thing really surprised me: Mercury’s supposedly minimal recording equipment – which I’d presume comprised little more than the three mics., cables, a three-track tape recorder, a 35 mm. film recorder and blank recording media – actually weighed in at four and a half tons! I dread to think how much a set of typical location-recording kit weighed.

Now for the best bit: the performances. This CD dropping into my lap brought it home to me that, although I had long been aware of his name, this would be the very first I had heard Janis playing. Quite how I’ve remained so ignorant for so long I haven’t a clue, but I’ve now learned to regret it.

Why “regret”? Well, over the years, I’ve heard a fair few interpretations of these two concertos, particularly the Prokofiev; so, on first listening to this CD, I fully intended to listen in comparative mode. It didn’t work out that way. Somehow, the music itself seemed to have acquired a distinct aura of “renewed unfamiliarity”. Bemused, I immediately played the disc again. The feeling persisted. Now, I think that I know why: it struck me that Janis had an uncommon knack of hoisting his listeners onto the crest of his wave, and keeping them there. This doesn’t mean that these performances leave the competition gasping in their wake; rather that they add an almost ineffable “something”, which makes them essential listening for anyone who loves these works. I might even venture that they are essential listening for anyone who does not love these works!

Inevitably, I had to wonder, just what is this “special quality”? And that, as Hamlet so succinctly opined, is the question! One reliable reviewer ascribed to Janis a lengthy list of qualities covering pretty well the entire gamut of pianistic technique. Having now heard Janis’s playing, I wouldn’t disagree with any of them – but not one of them was what I had in mind! Thus (there being no other options) I must conclude that this “special quality” is not a particular, but a general facility. I have in mind something like “an ability to animate the musical logic”, similar to but not the same as the more common “long view”. And so, uncomfortably aware that I may well be barking up the wrong tree entirely, I tentatively dub it “fluency”. In my mind at least, it is a real virtue.

There’s one general point to make about these concerto recordings: unlike the vast majority of his competitors, Janis never pares his sound right down to whisper-quiet. Now, this cannot be anything whatsoever to do with the recording, since one of the rules of Mercury’s “living presence” technique is that the engineer must set a recording level that just nicely accommodates the loudest passage, and thereafter must keep his hands off the faders. Hence, it must be a matter of choice on Janis’s part; but, I must stress that at no time do I feel that he lacks anything in the “poetic sensitivity” department. Of course, those who have difficulty hearing music when it’s pianissimo inafferrabile will be only too happy.

Both the recordings of the Prokofiev in my collection, Ashkenazy/Previn (Decca) and Marshev/Willén (Danacord), push the composer’s tempo markings towards their extremes. Thus the introductory andante becomes adagio and the ensuing allegro becomes presto molto, broadening out slightly for the bruising climax. Janis/Kondrashin palpably stick closer to the tempo markings, their andante relaxed yet properly mobile and their allegro prudently short of frenetic. This sets the scene for just one obvious example of Janis’s fluency at work: far from “broadening out slightly” for the climax, Janis presses on right through the climax before easing off. This renders that chordal climax positively pugnacious – and engenders a brutal edge that, need I add, is inherent in the music. It makes a world of difference; and, really, isn’t keeping the pot boiling over, at this particular point, the right way to go?

At the other end of the Prokofiev there’s an entirely different surprise. I’m thinking here of “that blood-curdling cycle of dovetailed chords” with which Prokofiev crowns his coda. Ashkenazy makes these thoroughly hair-raising, and Marshev runs him close; but both (along with just about everyone else, for that matter) render these as hair-raising, impressionistic “washes” wherein the alarming overall sound is the entire point. Janis is an – if not the – exception: he palpably points up the “inner detail” of what each hand is doing! Personally, I prefer the impressionistic wash that leaves me gasping with astonishment. I’m not at all convinced by an approach that seeks to lay bare its inner workings. That said, neither am I inclined to dismiss a performance as thoroughly exceptional as Janis’s on the strength of one brief, contentious moment.

I turn to the Rachmaninov First Concerto as one who does not love this work. I’ve always found it scrappy and disjointed, regardless of who’s playing it – which naturally enough has led me to “blame” the music. But now, along comes Janis, whose interpretation strikes me as being, if anything, even more impressive than that of the Prokofiev, because his “fluency” has completely eliminated whatever was turning me off. For the very first time, I was unequivocally engaged from first to last, enjoying every moment and basking in a new-found continuity both physical and logical.

I’m indebted to Janis, not least for restoring my faith in the integrity of Rachmaninov’s genius. Granted, I have one reservation: Janis’s tempo for the start of the finale. On the one hand it sounds somewhat rushed, but on the other maybe a slower tempo would have sacrificed overall cohesion and vitality. I’ll get used to it!

As it happens, I grew up with the Ashkenazy/Previn cycle; thus, although in most respects it stands as a benchmark, this must have been the one most responsible for putting me off the First Concerto. So, I listened more closely. I found that the “problem”, most prevalent in the first movement, lay in the moments of repose, which I now think are seriously over-cooked. Winding down until both amplitude and tempo drift into imperceptibility, the music seems to, well, die, and this need resuscitating – not exactly a comfortable feeling.

In my enthusiasm for Janis, I must not overlook the contributions of the Moscow PO and Kyril Kondrashin! When reviewing concerto recordings, the thought often crosses my mind: can we ever be sure how to apportion credit between soloist and conductor? At one extreme, the conductor could have been fully in the driving seat, and (more likely?) at the other the soloist could have held the whip-hand; or, indeed, anywhere in between. What we can divine is whether conductor and soloist were simpatico; which happy condition, almost by definition, lies at the heart of pretty well all truly outstanding performances. Judging by the pervasive frisson of these performances, Kondrashin and Janis spoke as one and, by the sound of it, every man-jack of the superb Moscow orchestra was with them all the way.

Prospective buyers beware! – Presto Classical stocks two distinct issues of these concerto recordings. On one, catalogue number 4853890 (download only, no booklet) these two concertos are all you get. On the other, catalogue number 434333-2 (CD or download, both with full booklet), here reviewed, you also get a 17-minute bonus comprising four solo “encores” – for practically the same price! If anyone can suggest a good reason for the existence of the download-only version, I’d be interested to hear it.

The Prokofiev Toccata, taken at a tempo which allows all the gory details to shine through, is gratifyingly savage. Playing Schumann’s Variations on the Theme by Clara Wieck with great flexibility, Janis raises formidably passionate climaxes out of the essentially funereal theme, and applies his pliant pianism most beguilingly to the altogether more wistful Mendelssohn Song without Words. Finally, there are the Three Scenes from Childhood by Octavio Pinto, a name entirely new to me. The music is arguably of even less consequence, and certainly far more pithy than, say, Bizet’s Jeux d’Enfants, but comparably entertaining – I particularly like the central March, in which Pinto and Janis conspire to conjure the muddy tramping of welly-shod small feet.

To summarise: regardless of a very minor reservation, this is a spellbinding disc, legendary recordings of legendary performances of these two concertos, rounded off with a neat “mini-recital” of four solo pieces. Go forth and buy – you will not be disappointed.

Paul Serotsky

Buying this recording via a link below generates revenue for MWI, which helps the site remain free