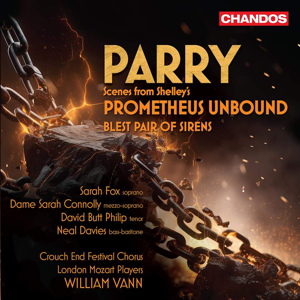

Sir Charles Hubert Hastings Parry (1848-1918)

Scenes from Shelley’s ‘Prometheus Unbound’ (1880)

Blest Pair of Sirens (1887)

Sarah Fox (soprano) – Spirit of the Hour; Dame Sarah Connolly (mezzo-soprano) – The Earth; David Butt Philip (tenor) – Jupiter/Mercury; Neal Davies (bass-baritone) – Prometheus

James Orford (organ)

Crouch End Festival Chorus

London Mozart Players / William Vann

rec. 2022, Church of St Jude-on-the-Hill, Hampstead Garden Suburb, London

Texts included

Chandos CHSA5317 SACD [71]

“Geography matters less in the United States than elsewhere in the world”, Vicente Verdú once wrote, adding that “the nation rounds itself off as an absolute space which seems to make reference to nothing but itself”. Lovers of classical music among “Columbia’s true sons” buck that stereotype by necessity; a fuller appreciation of the genre requires at least some awareness of the world beyond the contiguous forty-eight states, after all. Even so it shames me to admit that on the cusp of the grand old age of forty-two, the music of a number of European countries continue to evade my closer attention. Foremost, arguably, and for no good reason is England; the exceptions to this personal lacuna being the music of Delius and Searle, both very dear to me, and neither of whom fits easy archetypes of “Englishness”.

On my side of the Atlantic there is an enduring notion that the British musical press unduly celebrates the music of its own. It took a while, but I came to realize this was a load of baloney. Twenty-five years ago, however, that cliché was the gospel truth to me. When I first heard of Parry back then, it insinuated to me something trite, small-time; like the Cabazon Dinosaurs and “The Biggest Ball of Twine in Minnesota”, a homespun curiosity of mostly local interest. “Who has time for that?”, I thought.

So while re-reading Delius and his Music a few days ago, I was surprised that the brief mention of Parry’s Scenes from Shelley’s Prometheus Unbound as the spark that ignited England’s rebirth as “Das Land mit Musik” unexpectedly grabbed my attention. That was when I remembered that somewhere among the stacks of CDs back at home, there was a sealed copy of this Chandos recording waiting to be played.

Music in the Victorian Era must have been drab indeed if this earnest score was described by the violinist Prosper Sainton as possessing the “étincelle électrique so seldom found”. Hardly a trace of the stuff is perceptible to modern ears in this score. Readily evident, however, is Parry’s command of the musical language of his time and, more importantly, his skill in using it to create something that, if not necessarily destined to set the world afire, at least strives to be different.

Early audiences for Scenes from Shelley’s Prometheus Unbound, as Jeremy Dibble reports in his exceptional liner notes, did not miss this score’s subversive rumble and were, as a consequence, divided between delight and disdain. A product as well as victim of the late 19th century’s culture wars over the “music of the future”, the work is audibly loaded with what were once considered provocative Wagnerisms. A memorable instance occurs when the Chorus of Furies cry out, “Prometheus! Immortal Titan!” against an orchestral backdrop that distantly evokes Valkyries, albeit with their rage expressed circumspectly not on a mountaintop, but a tidy drawing room. Parry, one gathers, assimilated only the most immediately appealing aspects of Wagnerism. Symphonic structure, tone color, leitmotif, and demanding tessiture meant more to Wagner than the mere sum of their musical value. Like Christopher Nolan and Terrence Malick in our time, Wagner sought to immerse his audience in potentially transformative aural-visual-philosophical experiences that confronted them urgently with matters cosmological and metaphysical.

Artistic expression as a three-dimensional totality was beyond Parry. What he glossed from Bayreuth in Scenes from Shelley’s Prometheus Unbound is limited to a bit of wayward chromaticism and somewhat generous use of the orchestra, at least comparatively so for its time and place. An especially lovely example is the melancholy sarabande that opens the work. Mournful winds softly intone the introductory figure, echoed by low strings, followed by brass, then all threading one over the next in the ensuing fugato. Before one knows it, this prelude segues into the work itself, its brevity heightening the regret that there are not more moments like it, when the composer is not tensed with self-conscious effortfulness.

Handel’s ghost looms over much of this work and, though Parry tries to wrest himself from his forebear’s grip, he cannot bring himself to break free. A regretful “but not yet!” practically issues from the pages of this stylistically dithering score, like that of Saint Augustine before his conversion. More than Wagnerist, Scenes from Shelley’s Prometheus Unbound could arguably be described as post-Baroque, quite a feat with the 20th century just over its horizon; the frieze-like unfolding of its narrative also beckons spirits yet to come, most notably of the work that Stephen Walsh much later described as a “paradox of immobility rendered mobile”, Stravinsky’s Handelian-Verdian Oedipus Rex.

Blest Pair of Sirens, appended onto the end of the disc almost as an encore piece, demonstrates Parry wielding his craft with far greater fluency and originality. Although the Prelude to Act I of Die Meistersinger von Nürnberg hovers and occasionally flits its wings audibly, the work is ultimately and essentially Parry. Rather than being defined by his influences, here he takes control of them and soars.

The performances on this disc are so confident and secure, that I was surprised to learn after my first listening about the longtime neglect of Scenes from Shelley’s Prometheus Unbound. William Vann’s direction of the London Mozart Players and the combined vocal soloists and choir give the impression of coming from a community steeped in this music, of having lived and loved it for ages.

What Parry achieved in Scenes from Shelley’s Prometheus Unbound was not “transformative”, but the establishment of an inflectional point from where English music could begin to emerge from under the shadows of Handel and Mendelssohn. As Debussy once shrugged off Stravinsky’s The Firebird, “One has to start somewhere”. More than a fossil—a musical Archaeopteryx only interesting for documenting English music’s being and becoming—this loving recording affirms that this music, for all its occasional gaucheness, deserves to be heard more often.

Néstor Castiglione

Previous reviews: Jonathan Woolf (September 2023) ~ John Quinn (October 2023)

Help us financially by purchasing from