Déjà Review: this review was first published in July 2002 and the recording is still available.

Maurice Ohana (1914-1992)

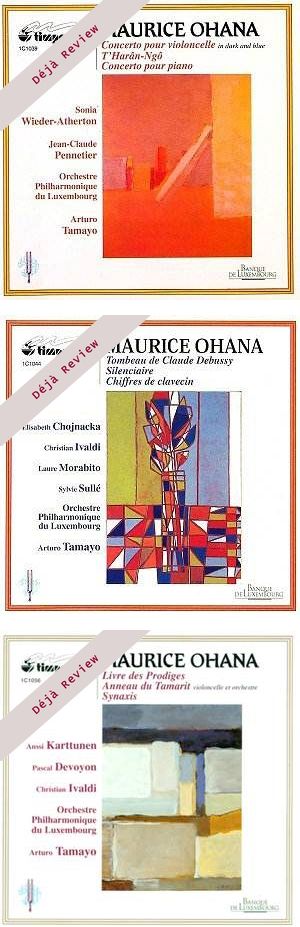

Cello Concerto No 2 ‘In Dark and Blue‘ (1990) ¹

T’Harân-Ngô (1974)

Piano Concerto (1981) ²

Sonia Wieder-Atherton (cello) ¹, Jean-Claude Pennetier (piano) ²

Orchestre Philharmonique du Luxembourg/Arturo Tamayo

rec. 1997, Conservatoire, Luxembourg

Timpani 1C1039 [65]

Tombeau de Claude Debussy (1962) ¹

Silenciaire (1969)

Chiffres de clavecin (1968) ²

Sylvie Sullé (soprano) ¹, Christian Ivaldi (piano) ¹, Laure Morabito (zither) ¹, Elisabeth Chojnacka (harpsichord) ²

Orchestre Philharmonique du Luxembourg/Arturo Tamayo

rec. 1998, Conservatoire, Luxembourg

Timpani 1C1044 [62]

Livre des Prodiges (1979)

Anneau du Tamarit (1976) ³

Synaxis (1966) ⁴

Anssi Karttunen (cello) ³, Pascal Devoyon, Christian Ivaldi (pianos) ⁴

Orchestre Philharmonique du Luxembourg/Arturo Tamayo

rec. 2000, Conservatoire, Luxembourg

Timpani 1C1056 [66]

It may be – and actually is – a truism to say that one’s background has a lasting impact on one’s life and achievements. Nevertheless Maurice Ohana’s multicultural background had an essential influence on his whole compositional work. He was born in Casablanca, then a French protectorate. His parents came from an old family of Sephardi Andalusian Jews. Moreover, his father, born in Gibraltar, was a British citizen, and Maurice Ohana remained a British citizen all his life though he lived in France from 1934 on. Thus, Ohana’s world centres around the Mediterranean Sea, i.e. Morocco, Northern Africa, Andalusia and France; and this all-embracing cultural environment played an important part in his musical make-up. His earlier works were strongly influenced by the Arabo-Andalusian culture. Works such as Tres Caprichos (1944/8) for piano, his Guitar Concerto (1940/50) reworked in 1957 as Tres Graficos and his first major masterpieces, the quintessentially Spanish Llanto por Ignacio Sanchez Meijas (1950) after Frederico Garcia Lorca and the beautiful Cantigas (1955).

Debussy and Varèse exerted a lasting influence on Ohana’s music, and the earliest work in the three CDs under review pays homage to Debussy. Tombeau de Claude Debussy was completed in 1962. It is scored for soprano, piano, third-tone zither (an instrument often used by Ohana) and orchestra. A remarkable feature of this work is that the scoring for limited orchestral forces nevertheless includes a sizeable percussion section (another Ohana characteristic). Ohana’s masterly use of percussion certainly echoes Varèse’s and Bartók’s; and percussion frequently features prominently in his output, e.g. Etudes choréographiques (1963), Synaxis (1966) and Silenciaire (1969) to name but a few. The score of Tombeau de Claude Debussy includes a few quotations from Debussy’s oeuvre, but they are buried deep in Ohana’s musical fabric and are obviously not meant to be clearly heard. (The most obvious quotation is a distorted one of La Marseillaise in the movement evoking WW1, an allusion to Debussy’s Berceuse héroïque.) Actually, this is a quintessentially Ohana score, and this impressive, demanding but deeply-felt masterpiece synthesises Ohana’s musical thinking and has all the main Ohana characteristics: micro-intervals, free polyphony, refined harmonies, masterly and often subtle use of percussion; but, above all – and most importantly – this often complex music eventually communicates by the sheer force of its expressive qualities.

On the other hand, Varèse’s influence may be clearly felt in Synaxis for two pianos, percussion (4 players) and orchestra, completed in 1966. This powerful, rugged piece is one of Ohana’s most original and personal achievements. Its often vehement, brutal sound world paints an almost inhuman, sun-drenched landscape of some unusual and often stunning beauty.

Ohana wrote a number of pieces for and with harpsichord and Chiffres de clavecin, completed in 1968, is the second of them. It is scored for small orchestral forces, still with a huge array of percussion. As is often the case in his output, the piece is made of several short movements, each in several subsections; and the global impact is that of a bright, colourful kaleidoscope rather than that of a tightly argued symphonic argument. Ohana’s music is typically built on hugely contrasted blocks of sound, evoking some eventful aural journey.

The use of percussion is still more prominent in Silenciaire (1969) for percussion (6 players) and strings. As in Syntaxis, the percussion section is an important protagonist; and, as Harry Halbreich rightly notes, “the strings serve as a sort of resonance chamber for the non-tempered and inharmonic spectrum of the percussion”. Again, though often quite gripping with some shattering climaxes, the music of Silenciaire also conjures up a refined sound world which is Ohana’s own.

As mentioned earlier, Africa had a deep influence on Ohana, who often evoked African rhythms and musical forms in a number of pieces all sharing the suffix Ngô in their titles (some of these have been invented by Ohana, but just think of Tango and Fandango). The orchestral work T’Harân-Ngô of 1974, incidentally his first purely orchestral piece, is one of them. In much the same way as most Ohana pieces, it may be experienced as some mysterious, primitive ritual. (According to the composer, the suffix Ngô also seems to characterise tribal dances and incantations)

Spain and Lorca were never absent from Ohana’s mind for long; and in 1976 he completed his first cello concerto Anneau du Tamarit paying another homage to Frederico Garcia Lorca. This beautifully moving work is mainly elegiac in mood, though it has its more turbulent, intense moments; but on the whole the music, though emotionally charged, communicates with restrained dignity. A pure masterpiece.

Some sort of ritual also lies at the heart of Ohana’s orchestral masterpiece Livre des Prodiges dating from 1979. Scored for large orchestra, the work falls into two large sections of fairly equal length, each made of several shorter subsections. One of these, Clair de Terre, acts as a refrain throughout the piece. The composer describes the work as a suite of images evoking timeless prodigies still haunting the contemporary mind, and as a concerto for orchestra rather than the symphony it might have been. Each section is vividly characterised and the work, as a whole, displays Ohana’s orchestral mastery and ear for stunning sonorities from first to last. This is undoubtedly his greatest masterpiece.

The solo part of Ohana’s Piano Concerto, completed in 1981, is quite remarkably idiomatic while retaining some sense of improvisation. (It is often written without barlines, which allows for some freedom on the pianist’s part, though the composer always keeps a firm grip on the work’s structure.) The Piano Concerto is in one single movement falling into four clearly characterised sections, of which the third one – and the longest as well as the emotional heart of the whole piece – is a stylised Saeta (i.e. improvised chant generally sung during the Holy Week in Andalusia).

Ohana’s last concerto and also his last major orchestral piece is the Cello Concerto “In Dark and Blue” written in 1990 for Rostropovich, who gave the first performance in 1991. As implied in the title, the Second Cello Concerto alludes both to Africa and to Afro-American music (i.e. jazz). This is particularly evident in the central Blues, a homage to Louis Armstrong (the composer wrote “Here’s to you, Satchmo!” in the score). As a whole, the Second Cello Concerto is the most tuneful, colourful and approachable major work here; a beautiful, sunny, heartfelt piece of music.

So, these three CDs include pieces spanning nearly thirty years of Ohana’s composing career and thus provide for a very comprehensive survey of his varied and substantial output. Moreover, all these pieces belong to his finest achievements, full of the composer’s gripping, refined (even in its violence) and viscerally communicative music.

All performances are excellent and could hardly be bettered, and make the best of each piece. All soloists are superbly equipped, dedicated players who obviously love this music, whereas Arturo Tamayo and the Orchestre Philharmonique du Luxembourg (a fine body of players) support them with commitment and conviction. Excellent, informative notes by Harry Halbreich.

These discs offer the best possible introduction to Ohana’s idiosyncratic sound world, which may be difficult, sometimes hard-edged but is always strongly communicative in its own personal way; but if you do not know Ohana’s music, I suggest that the first disc listed in the above is the one to start with.

Hubert Culot

See also Dave Billinge’s review of Timpani 1C1044 (July 2002)

Buying this recording via a link below generates revenue for MWI and helps us keep free access to the site