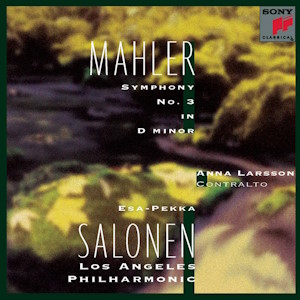

Gustav Mahler (1860-1911)

Symphony No. 3 in D minor

Anna Larsson (contralto)

Women of the Los Angeles Master Chorale; The Paulist Boy Choristers of California

Los Angeles Philharmonic/Esa-Pekka Salonen

rec. 1997, Dorothy Chandler Pavilion, Los Angeles, California

German texts and English & French translations included

Presto CD

Sony Classical S2K 60250 [2 CDs: 94]

Not long ago I reviewed a brand-new recording by a US orchestra of Mahler’s Third. That was a live performance from November 2022 by the Minnesota Orchestra and their recently departed music director, Osmo Vänskä. Now, I have had the opportunity to review another American recording in the shape of this 1997 account by the Los Angeles Philharmonic which Presto Classical have licenced for their on-demand CD service. In this recording, which I think was made under studio conditions, the LAPO were conducted by Esa-Pekka Salonen. I don’t intend making detailed comparisons between the two performances, not least because Vänskä’s recording is live and as far as I know Salonen’s is not; however, it’s interesting to note that the Vänskä performance took 104 minutes, whereas Salonen takes ten minutes less.

It was with Mahler’s Third that Salonen’s conducting career took a huge step forward. In 1984 he replaced the indisposed Michael Tilson Thomas who was scheduled to conduct the Philharmonia Orchestra in a performance of this symphony in London. Salonen had never conducted it before – I’ve read that he learned the score in a week – and the success he achieved in leading this vast score at minimal notice made people sit up and take notice. The Philharmonia appointed him as principal guest conductor the following year (until 1994) and he later became the orchestra’s principal conductor (2006-21). Meanwhile, he also built a relationship with the LAPO, succeeding André Previn as their music director in 1992; he held the post until 2009. So, this present recording was made at a time when the relationship between Salonen and the LAPO was securely established: it shows.

It’s worth mentioning one interesting feature of this recording before I go any further. Sony divided each movement into a number of tracks; so, for instance, the huge first movement has seven separate tracks and the finale has six; even the comparatively short fourth movement, which only plays for 8: 35, is divided into two tracks. Although I can’t imagine many people wanting to dip into a section of this vast symphony, the track division is quite handy in reminding you where you are in a particular movement.

The opening of the first movement is very promising. The unison horns ring out splendidly and I like the way the recording allows you to hear space around the instruments. Salonen sets a purposeful pace. A little later, the big trombone solo is imposingly delivered by Ralph Sauer. The quick march that follows (disc 1, track 3) is quite brisk; in this section the LAPO offers playing which is crisp or delicate, as the music demands. However, as the movement unfolded, I began to wonder if the pace was not perhaps just a little too brisk. Salonen’s treatment of the music is clear-eyed and has more than a touch of exuberance. I admire the freshness of his approach but arguably the interpretation misses some of the nuances and flexibility I’ve heard from other conductors. I should add that Salonen can be weighty when required – in the passages involving the trombone solos, for example – but often the pace is somewhat breathless. That said, it’s hard to argue with the exhilarating way that Salonen and the LAPO deliver the last 4 or 5 minutes of the movement. Sony give individual track timings but not the overall per-movement times; out of interest, I totted up the track timings for the first movement and it emerges that Salonen gets through it in 31:34; that’s one of the swifter overall accounts I can recall.

Salonen makes a good job of the second movement; the music is nicely pointed. That’s also true of the scherzando episodes in the third movement. The solo posthorn is atmospherically distanced – though not so much as in the recent Vänskä recording – and Donald Green plays it very well. However, I can’t help feeling that Salonen’s speed for the posthorn passages is just a little too fleet; he doesn’t quite convey the magical air of nostalgia. The last stretch of music (track 14), following the final appearance of the posthorn, is decidedly swift, so much so that in the last few pages Salonen comes close to rushing the music off its feet.

The fourth movement brings us the voice of the Swedish mezzo Anna Larsson. She sings with burnished tone and I like the clarity of her singing. When I reviewed the Vänskä recording I commented that most conductors in my experience have taken between about 8:40 and 9:40 for this movement (Vänskä, who is very spacious, takes 10:25). Salonen is at the quicker end of the spectrum; his performance plays for 8:35. Some listeners may feel his relatively swift speed sacrifices some of the music’s dark mystery; I wouldn’t quarrel with such a view but I have to say I approve of the flow that he brings to the movement. One small point of detail: Salonen’s oboist eschews the upwards glissandi that a number of conductors have encouraged in recent years – Simon Rattle was one of the first to feature this device on disc, I believe (review). So far as I know, the gesture is stylistically authentic but I have never liked it; the effect is ugly and I’m pleased that Salonen has the oboe part played ‘straight’. The short fifth movement is bright and breezy; you won’t be surprised to learn that the speed is swift. Both choirs offer fresh, lively singing. I enjoyed this movement. Incidentally, Sony ensure that the last three movements follow each other with virtually no pause, which is how it should be; not all recordings achieve that effect.

In the opening paragraph of the concluding Adagio, the playing of the LAPO string choir is magnificent. Salonen paces the music well, I think, allowing Mahler’s lines to flow in a very natural way. I scribbled in my notes “purposeful, but he doesn’t miss the poetry”. As the movement unfolded, I admired very much the conductor’s expert control and the orchestra’s distinguished playing; whilst other readings have moved me more, this one is still very good. When the brass take up the theme as a kind of chorale (track 9, 0:43) the principal trumpeter plays with a wonderful silvery tone. In the last three or four minutes you might reasonably argue that Salonen could have invested the music with a fraction more breadth but, that said, the playing of the LAPO ensures that the music is still majestic.

In many ways this is an admirable Mahler Third. Salonen seems to have a clear sense not only of where each movement is going but also of the overall trajectory of the symphony. Such reservations as I have concern some tempo selections, which at times seem to me to be on the brisk side. However, other may not share that view and, in any case, I think Salonen’s way with the music is refreshing overall. His interpretation is supported by terrific playing by the members of the LAPO; collectively they are excellent and there’s also an abundance of delightful solo work to enjoy.

The recorded sound is very good. Tim Page’s notes are adequate.

Salonen’s is probably not the first version of the Third that I’d take down from the shelves if I were listening to the symphony for leisure rather than reviewing purposes. That said, it has got a lot going for it and I’m glad that Presto Classical have restored it to circulation, enabling me to add it to my collection.

John Quinn

Buying this recording via a link below generates revenue for MWI, which helps the site remain free