Déjà Review: this review was first published in July 2002 and the recording is still available.

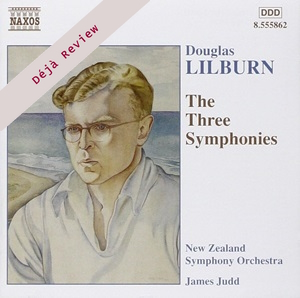

Douglas Lilburn (1915-2001)

The Three Symphonies

Symphony No 1 (1949)

Symphony No 2 (1951)

Symphony No 3 (1959)

New Zealand Symphony Orchestra/James Judd

rec. 2001, Michael Fowler Centre, Wellington, New Zealand

Naxos 8.555862 [77]

At the outset I would like to state that this disc is one of the most important Naxos have so far released; this may be a brave claim but, as well as making this superb music available at true budget price, it will also function to greatly raise the public profile of this incredibly talented but underrated composer. Much as I love the Continuum recording (from 1992/3, with the same orchestra, under John Hopkins), and the ethos of Murray Khouri’s label in general, this disc is much more likely to be bought or encountered by the classical consumer at large. Continuum is not a recording enigma of Lyrita proportions, but you are not particularly likely to come across its discs while browsing the racks of your local HMV!

Lilburn grew up, surrounded by unspoilt nature, on a remote North Island sheep station and also studied with Vaughan Williams for a while. I mention these biographical details merely as starting points, rather than as an attempt to categorise his wonderful body of work. That said, the uninitiated listener would immediately recognise that this music is different and couldn’t possibly have been conceived within the geographical and artistic confines of the central European tradition. Even the VW connection is, to my mind, a bit of a red herring; one needs to look northwards, to Sibelius, Nielsen, Tubin maybe, or out to the pioneering west of Roy Harris (the justly celebrated third symphony especially), to see any real parallels of feeling or form. The only British works I would care to mention in the same breath, and then with reservations about the intensity and distillation, are the first symphonies of Moeran and, possibly, (Arthur) Butterworth. Whatever, Lilburn’s music absolutely lives and breathes the environment (not just the landscape, and certainly not as restrictively and programmatically as the otherwise excellent booklet notes might have us believe) of the latitude (and longitude?) in which it was evolved.

The first two symphonies belong, artistically, to the main body of Lilburn’s first mature style, along with shorter but very valuable works like the Drysdale Overture and A Song of Islands (beautifully recorded and compiled on another Continuum disc). The idiom is one which is at once bracing and expansive, in the Nordic sense. It often recalls, but certainly does not imitate, the later symphonies of Sibelius and Nielsen, the marvellous second of Stenhammar and maybe, even further afield, Rubbra’s less severe essays in the medium or Bax’s more focused moments. The “scotch snap” is definitely in there, perhaps as a subconscious motif from Lilburn’s ancestry! In every sense, the works come across as organic, impressively structured ones (and very strongly in this perceptive reading), with a true symphonic sense of development and forward momentum. The third symphony is less immediately accessible but is only “difficult” in the same way that, say, Nielsen’s Fifth is in relation to the four that went before it (ie. compared to a lot of contemporaneous offerings, not very!).

So to this particular recording – the orchestra, as mentioned above, is the same one which played on the Continuum disc (CCD1069) and Lilburn’s music is something that is clearly and quite rightly in their blood. James Judd is perhaps not as high profile a conductor as others on this (or any other) roster, but he has some notable successes under his belt (his Elgar first still takes some beating) and this could well join the list of his performances to cherish.

The First Symphony of 1949 consists of two outer allegros, given a slightly more expansive treatment by Judd than Hopkins (on Continuum), framing a central rondo based andante. It would, for this listener at least, have single-handedly confirmed Lilburn’s mastery even if he had written nothing more in the medium. The Second, completed two years later, is, in many ways, even more accomplished. This time Lilburn used a four movement structure, including, unlike the first, a scherzo. Judd’s overall timing is virtually identical to Hopkins’ but there is minor variation between individual movements. Over-analysis of such matters does, however, no service to music that is more than capable of speaking for itself and has, without exception, received strong and convincing advocacy in all the (pitifully few) recordings it has so far engendered. The more astringent Third Symphony, cast in a single movement of five linked sections, is perhaps destined, like, for example, Sibelius’ fourth, sixth and seventh symphonies, to elude wide-scale popular acceptance. It represents a formidable apotheosis for Lilburn’s (even) more economical, pared-down second phase. In this phase Stravinsky and early/late (rather than populist mid-period) Copland were, perhaps, more accurate touchstones than the Nordic composers.

This disc, although I have (very) slight reservations about the sound (not the performance!), is worth far more than the modest asking price. It ought, in a fair world, do for Lilburn what the same company’s discs have done, in the recent past, for composers like Finzi and Bax. His music is just waiting for mass discovery and appreciation and, if you only buy one CD this year, make sure it is this one.

Neil Horner

Buying this recording via a link below generates revenue for MWI and helps us keep free access to the site