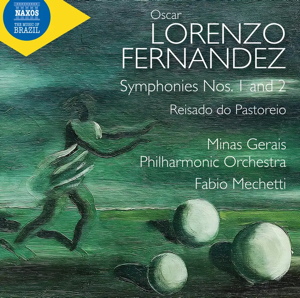

Oscar Lorenzo Fernández (1897-1948)

Reisado do Pastoreio (1930)

Symphony No.1 (1945)

Symphony No.2 ‘O Caçador de Esmeraldas’ (1946-47)

Minas Gerais Philharmonic Orchestra/ Fabio Mechetti

rec. 2022, Sala Minas Gerais, Belo Horizonte, Brazil

Naxos 8.574412 [83]

Another release in the Naxos “Music of Brazil” series – the 22nd I think. Another composer almost completely unknown outside of Latin America. Another revelation. This is a tremendous disc of music of real interest and quality played with exciting commitment and verve. Collectors of this series need read no further – get this disc! For others some brief biographical detail may help. Oscar Lorenzo Fernández was a driving force in the musical cultural life of Rio de Janeiro up until his untimely death aged just 50 in 1948. His career spanned composition, teaching and conducting and he founded various institutions and publications. He still found time to compose a substantial body of work from operas to chamber music and including the two symphonies included here – he did not live to hear the Symphony No.2 premiered. Of the three works offered here, only one is marked “world premiere recording” which suggests that in – presumably – Brazil these impressive works have been recorded and are better known. As a composer, for the wider world, Lorenzo Fernández’s tenuous grip on fame rests on a single brief work – the 4:10 Batuque which forms the third and final movement of the suite Reisado do Pastoreio (A Pastoral Epiphany) recorded here. Batuque became a ‘pops’ favourite with composers as diverse as Toscanini, Koussevitsky, Bernstein and Chávez. The attraction of this movement is instant and obvious – perhaps more of a surprise is that much of the rest of the music is of equal appeal and interest. Lorenzo Fernández belonged to the group of Brazilian intellectuals and artists who sought to create work that reflected Modern as well as Nationalist creative ideals. Lorenzo Fernández’s first success was with a tone poem named Imbapara which sought to invoke the culture of Brazil’s indigenous people through the use of themes collected by anthropologist Edgar Roquette-Pinto.

The warmth of the reception encouraged Lorenzo Fernández to explore such musical sources further in the Reisado do Pastoreio of 1930. The three compact movements – the work runs to 13:12 in total – are titled Reisado (‘Epiphany’), Toada (‘Song’) and Batuque. The opening two movements are genuinely attractive – lyrical and evocative. One thing that becomes immediately apparent – and holds true throughout the disc – is just how effectively Lorenzo Fernández orchestrates. According to the fairly brief Wikipedia entry he studied at the Instituto Nacional de Música with Francisco Braga, Frederico Nascimento, and Henrique Oswald and before his embracing musical Nationalism his early works were Impressionist. Certainly Reisado and Toada seem to fuse the folk-musical spirit of Brazil with a quasi-impressionist evocation of the countryside. Notable too is the quality of the playing of the Minas Gerais Philharmonic Orchestra under Fabio Mechetti. The woodwind principals have opportunities throughout to play with elegance and grace which contrasts nicely with the bite and swagger of the brass in the more overtly machismo movements. Batuque certainly constitutes one of those but it displays the sophistication of Lorenzo Fernández’s writing with melodic and rhythmic fragments repeated and developed in an obsessively compelling way. There are more than a few echoes of other Latin American composers – perhaps most obviously Ginastera in his Nationalist phase although Lorenzo Fernández predates the younger Argentinian’s best-known works. Batuque appears on other collections of Brazilian/Latin American ‘pops’ – most notably on a BIS disc with Roberto Minczuk and the São Paulo Symphony Orchestra titled “Danças Brasileiras” and another collection form Dorian “Danzón” where Keri-Lynn Wilson conducts the Simon Bolivar Symphony Orchestra of Venzuela. All three versions are exciting – but hard not to hear the São Paulo ensemble as the most sophisticated. Highlight though Batuque is, the entire suite has a scale and proportion to it that makes for a very enjoyable listen – just the kind of work that struggles to be programmed in the concert hall these days despite its considerable merits.

Ricardo Tacuchian’s useful liner explains that by the time Lorenzo Fernández came to write his Symphony No.1 in 1945 he had abandoned the explicitly Nationalistic style embodied by Reisado do Pastoreio. That said, while the musical material might no longer have the clear shape and style of his folk heritage there are passages that clearly speak of his Latin American roots. Both symphonies follow a traditional four movement form with a scherzo second and intense slow movements third. Symphony No.1 receives its world premiere recording here and proves to be an effective and powerful work. In total it runs for 31:47 and has a good formal balance where the opening Lento (ad libitum) – Moderato at 10:14 is balanced by the closing Allegro energico of 8:12. The central pair of Allegro vivo e scherzoso and Lentamente are roughly 6 and 7 minutes respectively. The result is a compact concentrated work of considerable drama. If you like your symphonies red-blooded and incident-filled this will appeal. The central pair of movements are particularly impressive with the driving toccata-like adrenalin-fuelled Allegro vivo e scherzoso very clearly belonging to that family of Latin-American dance styles that are both exciting and instantly memorable. Likewise the intense cumulative power of the following Lentamente is effective both through Lorenzo Fernández’s handling of the orchestra and his pacing of the climax. The closing movement is slightly curious in that it starts with a brass fanfare that seems more like a Korngold film score out of a Bliss coronation but over the course of the movement that material morphs into something more explicitly Latin American. Throughout both the playing and the interpretation sounds and feels effective and ‘right’. Perhaps the soundstage is a little cinematic in its close detail and relative lack of warmth but the playing itself – especially from the woodwind, brass and extended percussion – is wholly impressive.

The Symphony No.2 ‘O Caçador de Esmeraldas’ [The Emerald Hunter] is written on a slightly more extended scale with its four movements lasting 36:02. The Emerald Hunter of the title was a 17th Century Brazilian Explorer who devoted his life to both exploring the then unknown interior of Brazil and his quest to discover Emerald Mines. These exploits were then enshrined in a 276 line poem by the Brazilian poet Olavo Bilac around the turn of the 19th Century. This might imply a highly detailed programme symphony but nothing in the liner or movement titles – which are just standard tempo indications – would suggest that. All that Tacuchian writes is; “As the music progresses [Lorenzo Fernández] conjures atmospheres of hope, heroism, struggle, discovery, delirium and death”. The explorer – Fernão Dias Paes Leme – did discover his emerald mines but died of a fever in the jungle clutching a bag of the jewels. Certainly the music seems more illustrative than the previous symphony – the opening rather confidently ‘setting forth’ before becoming less certain and fraught. The second movement is again a truly brilliant scherzo – here marked Molto Allegro e misterioso with cross-metered rhythms seeming to suggest dancing or battles within the space of a few bars. Again all credit to the hard-working Minas Gerais Philharmonic Orchestra who play this far from straight-forward or predictable music with absolute confidence and considerable flair. The third movement Lento e lamentoso is less explicitly dramatic than its counterpart in the earlier symphony – the ‘lamentoso’ direction seems key to suggesting perhaps a sense of grieving or loss rather than anger or outrage. The woodwind principals once more excel with playing of real sensitivity and poise. The finale opens as a confident dynamic Allegro mosso e agitato but about halfway into its 7:04 duration this energy seeps away and the closing three minutes of the symphony has the feel of a steady but rather heroic funeral procession before the music fades away into a jungle gloom.

Both of these symphonies are quite traditional in their formal and musical goals – certainly when they are placed in the wider global context of music written in the immediate aftermath of World War II – Tacuchian suggests Bartok as an influence. But even allowing for that essential conservatism, the confident handling of the material, the impressive sweep and impact of both works makes for a sense of real discovery of a significant composer with an individual voice. The Wiki entry mentions a further five symphonic poems, two orchestral suites and one concerto each for piano and for violin. The hope must be that at least one further disc in this series will be devoted to some of those scores. This project by the Brazilian Ministry of Foreign Affairs to promote the music written by Brazilian composers has proved to be a resounding success with the exposure given to so many fine works ample proof of the diverse quality of the music-making in the country. Of course, the assumption must be that the same would be true if other Latin American countries showed similar commitment. A fine and generous survey makes this a genuine discovery.

Nick Barnard

Buying this recording via a link below generates revenue for MWI, which helps the site remain free.