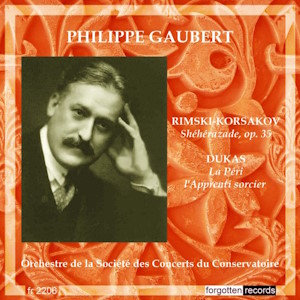

Nikolai Rimsky-Korsakov (1844-1908)

Scheherazade, Op.35 (1888)

Paul Dukas (1865-1935)

La Péri (1912)

L’Apprenti sorcier (1897)

Orchestre de la Société des Concerts du Conservatoire/Philippe Gaubert

rec. 1928-29 (Rimsky and Le Péri), December 1936, Studio Columbia, Paris

Forgotten Records FR 2206 [70]

Scheherazade was first recorded in full in 1924 by Eduard Mörike and the Berlin Symphony Orchestra. By then individual movement had also been recorded by conductors as varied as Ansermet, Ysaÿe, Coates, Stokowski, Landon Ronald and one Dirk Fock. Stokowski was soon to record it in full in 1927 and soon after came Philippe Gaubert’s 1928-29 set, recorded for French Columbia.

Mörike took ten 78 sides to get through it though I’m not sure if his recording was cut – I suspect it was though I’ve never heard it. Gaubert took eleven sides. There’s no reason why he couldn’t have taken twelve but he chose eleven and therefore there’s a cut in the final tableau between sides ten and eleven – some 40 or so bars. It doesn’t destabilise things but it’s a pity.

Gaubert was a fine conductor, not quite as fine a conductor as he had been a flautist, but a largely unmannered and direct practitioner. Scheherazade responds best to colour-conscious, luscious interpreters though ones with a strong sense of orchestral discipline. Stokowski was an ideal medium for Rimsky’s cinematic glamour and if he had his own idiosyncratic take it was a truly expressive one. Gaubert is not that kind of conductor and his orchestra exudes a very different corporate identity to the Philadelphians. The brass section is strong and the winds have very distinctive tonal qualities, without very much vibrato. I find them characterful and attractive but they won’t please everyone. Fortunately, the recording was a fine one so frequency response in the Studio Columbia, Paris is immediate. The concertmaster isn’t mentioned – I’m not sure he has been identified – but it’s certainly not Henry Merckel, who was to join the orchestra somewhat later. This leader has a decidedly elfin sound and plays with quick but frequent slides.

I don’t think it’s a lumpy side-join in The Tale of the Kalendar Prince that leads to the retarding of rhythm – I think, rather, it’s a Gaubert mannerism. The most obvious example of period practice comes in The Young Prince and the Young Princess where the effect of the uniform use of portamenti gives the music a very sea-sick feel. That might have worked better in the finale, The Festival of Baghdad, where the violin soloist, whoever he is, is at his least impressive. The performance as a whole is good, not outstanding, and lacking in the kind of sonic amplitude that Stokowski received.

In April 1928, just before Gaubert embarked on his Rimsky sessions – sessions that stretched into 1929 – he recorded Dukas’ La Péri and did so with ardour and urgency. He controls the rhetoric in exemplary fashion, drawing out the music’s power and proves yet again what an eloquent and attractive exponent he was of the modern French School. That feeling is reinforced by his 1936 recording of L’Apprenti sorcier. For a wider look at his native repertoire you can do a lot worse, if you can find it, than a Malibran disc containing some fine recordings made at the same time as the ones in the disc under review (review).

Gaubert’s early Scheherazade is specialist territory, of course, and even by contemporaneous standards somewhat compromised but it shows his control of structure and tone, and reveals once again the very idiosyncratic qualities of this orchestra. There are no notes, just a few internet links, but the fine restorations add to the pleasure of the disc.

Jonathan Woolf

| Availability |  |