Ennio Morricone (1928-2020)

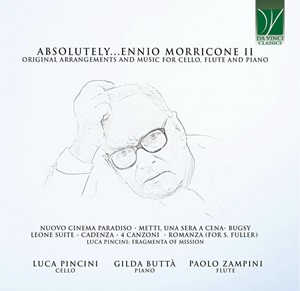

Absolutely … Ennio Morricone Vol 2

Original Arrangements and Music for Cello, Flute and Piano

Gilda Buttà (piano), Luca Pincini (cello), Paolo Zampini (flute)

rec. 2023, Abbey Rocchi Studios, Rome, Italy

Da Vinci Classics C00580 [60]

With every release of music by Morricone, I expectantly look out for others of his many film scores and his concert works. Disappointingly, the familiar scores from the Once Upon a Time and Dollar trilogies, and a handful of others, are usually again trotted out. This is all gorgeous music, which I love, but I now have more than enough orchestral versions and arrangements of these to satisfy me forever. Time for something different, please. As for his concert works – practically nothing gets above the parapet.

This recording is the second volume in the series, Absolutely … Ennio Morricone, compiled by Da Vinci Classics. Volume 1 was released in 2022 and has not been reviewed on MusicWeb International. The format of the two volumes is similar, comprising mainly arrangements for instrumental ensemble, or soloist, of music adapted from his orchestral film scores – termed his ‘applied’ music by Morricone – together with a few independent concert pieces, his ‘absolute’ music. Some of the less well-known film scores and the few pieces of his ‘absolute’ music which appear on this disc and Volume 1 are to be welcomed. The trio of soloists on this disc have previously also recorded some of these pieces for Warner Classics on the 2-disc Morricone: The Man and his Music, reviewed favourably by Gary Dalkin and Michael McLennanin (review).

Morricone was born in Rome and lived there all his life. His father, Mario, was an orchestral trumpeter who taught Ennio to read music and to play a variety of instruments before he was a teenager. He studied trumpet and choral music at the Conservatorio di Musica Santa Cecilia and, later, composition with Goffredo Petrassi, who was considered one of the most influential Italian composers of the 20th century. Petrassi’s music was typically neoclassical in style, but he later experimented with a variety of post-Webernian influences. Some of the influences of Petrassi’s language evidently rubbed off on Ennio.

Morricone’s career in the 1950s was busy and consisted of uncredited ‘ghost’ writing of background music for theatre, radio, television and film; arrangements of songs by jazz and ‘pop’ singers; a stint as a successful studio arranger for RCA Victor and playing trumpet in jazz bands. All the while he was composing works for the concert hall, few of which were recorded and some of which, perhaps, have never been performed. His first credited film score was written in 1961 for Luciano Salce’s Il Federale (The Fascist). He went on to write over 400 ‘applied’ music scores for films and television series. Some of his most successful and enduring collaborations were with Giuseppe Tornatore, Luciano Salce, Bernardo Bertolucci, Sergio Leone, Brian De Palma, Roman Polanski, Warren Beatty and Quentin Tarantino.

His music was influenced by his active involvement in the musical avant-garde and experimental music. From its formation in 1964 until its disbandment in 1980, Morricone was a core member of Gruppo di Improvvisazione Nuova Consonanza (known as Il Gruppo), a group of Rome-based composers. They performed and recorded avant-garde free improvisations, drawing on jazz, serialism, musique concrète, improvisation, noise-techniques, anti-musical systems and other avant-garde techniques. It was dedicated to the exploration of ‘New Consonance’ and included composers Luigi Nono and Giacinto Scelsi. The ‘New Consonance’ movement later produced composers like Rautavaara, Pärt, Corigliano, Gorecki, Higdon, Kernis, Reich, Nyman, John Adams and Philip Glass. Highly regarded in avant-garde music circles, Il Gruppo is considered to be the first experimental composers’ collective.

Much of the musical experimentation by Il Gruppo is evident in Morricone’s music. Quoting from the Ennio Morricone website, “It is impossible to recall Leone’s films in the mind’s eye or ear without Morricone’s music … From the early whipcracks, bells, whistles, Italian folk instruments, incomprehensible lyrics and Fender Stratocaster riffs – which may have been distant spin-offs from Morricone’s researches into John Cage and the idea that all sounds can belong to the realm of music – to the romantic score from America [Once Upon a Time in America] with its wistful Eastern European pan-pipes and dense orchestral textures, the work of these two artists ran on parallel lines … The opening bars of The Good, The Bad and The Ugly, with their “Ay-ee-ay-ee-ay” coyote howl, are among the most instantly recognisable in the history of the movies”.

The music on this disc is all from the hand of Morricone, except for Fragmenta of Mission. More about that later, but Morricone famously did not approve of arrangements of his music by other composers.

Nuovo Cinema Paradiso for piano is based on the opening titles piano music from the 1988 coming-of-age comedy-drama by Giuseppe Tornatore. It is sentimental, nostalgic, innocent and moving – a successful, straight transposition from the original score.

Metti, una sera a cena for flute and piano (very loosely translated, “Imagine, an evening having dinner”), also known as ‘Love Circle’, is a 1968 Italian drama involving a rather complicated ménage à cinq meeting over dinner and playing their games of seduction. This is uneasy lounge jazz/bossa nova influenced music, and the developing conflicts amongst the protagonists are well-characterised.

Rag in frantumi (Rag in pieces) for piano is a concert piece from 1986 in which, Giovanni D’Alò in his booklet notes says, Morricone “… playfully shreds a ragtime, taking the term ‘to rag’ quite literally (meaning to tear apart).” It sounds like something written by Scott Joplin, torn apart in frustration and desperately re-assembled by Stravinsky or György Ligeti. Playful and enjoyable.

Bugsy for flute and piano uses music from Barry Levinson’s 1991 crime drama on the life and death of American mobster Benjamin “Bugsy” Siegel. The film’s sentimental, melancholic and inevitably tragic score is well caught in this flute and piano arrangement.

The Leone Suite for cello and piano brings together themes composed for the Sergio Leone films, Once Upon a Time in America, Once Upon a Time in the West and The Good, the Bad and the Ugly.

Deborah’s Theme is from Once Upon a Time in America (1984), the third in Leone’s Once Upon a Time Trilogy. The story deals with Jewish youngsters growing up in poverty in the Lower East Side of New York, their only hope of achieving the ‘American Dream’ being through crime. The sad, bittersweet music for the abused and tragic Deborah Gelly is heart-rending. This and the Main Theme adaptation for cello and piano are finely done, but I do miss the ravishing orchestral original, pan-pipes and all.

Cockeye’s Song, also from Once Upon a Time in America, epitomises the happy-go-lucky Philip “Cockeye” Stein. Like all the other pieces in the Suite, there is virtuosic writing for the cello here. As D’Alò comments: “The result is nothing short of astonishing – when placed in a chamber music context, these iconic themes … rejuvenate and become concert pieces in their own right.”

Once Upon a Time in the West, from 1968, is an epic ‘spaghetti’ Western, the first instalment in Leone’s Once Upon a Time trilogy. This film is much more deliberate in pace and sombre in atmosphere than Leone’s other Westerns. The cello and piano arrangement does well to bring out this mood with some delicious cello writing. But again, I yearn for the haunting atmosphere lent by the harmonica, the Stratocaster riffs and the inventiveness of the nonmusical devices used to create tension in the orchestral score.

The Ecstasy of Gold is from The Good, the Bad and the Ugly, a 1966 iconic ‘spaghetti’ Western, the third and final instalment in the Dollars Trilogy. The Italian Westerns differed from their American counterparts in dealing with morally complex anti-heroes, themes of greed, cruelty, revenge and an operatic approach to violence, as is the case in this film too. The film’s climax, a three-way Mexican stand-off, begins with the melody, The Ecstasy of Gold. The cello and piano arrangement here is impressive, but falls short of the epic proportions of the orchestral score. Shorn of its two-note ‘howling coyote’ motif, whistling, riffs on banjo and electric guitar and the unique wordless vocals of Edda Dell’Orso – a Genoese soprano with a dramatic three-octave range and a long-time muse to Morricone – it is far less effective.

The Cadenza for flute and magnetic tape composed in 1988, grew out of the flute solo material from Morricone’s Second Concerto for flute, cello and orchestra. The piece clearly draws on the influences of the 1960s avant-garde and Morricone’s contact with electronic technologies and experimental techniques with Il Gruppo. His use of live sounds and recorded tape was unique and D’Alò comments that: “The magnetic tape is created by combining three layers of sound: at the base lies a citation of the first six notes from a Ricercare by Gerolamo Frescobaldi, elaborated into sinusoidal waves, while the second and third layers reproduce, in a staggered fashion, the part that the flutist performs live”. The contrapuntal combination of the tape layers and the live flute part creates complex rhythms and dissonant harmonies; a different side of Morricone, but not an easy listen.

The 4 Canzoni for piano uses themes from four less well-known films, with no or minimal alteration, to create a suite for concert performance. I particularly enjoyed these complex and beautiful, seldom heard pieces. Il Deserto Dei Tartari (The Desert of the Tartars) is a 1976 film about a remote garrison outpost guarding the desert frontier from the Tartars. Time passes slowly with no other expectation than the wait for death. The Kafkaesque tale makes for uneasy, disturbing music – brooding, listless and unbalanced. Le Due Stagioni della Vita (The Two Seasons of Life) is a 1972 Belgian drama which deals with the two stages in the life of Guss: as a boy whose mother is separated from the family; and as a young man embarking on an artistic career; the music is lyrical and tense. Gott mit Uns (also known as The Fifth Day of Peace) is a 1970 Italo-Yugoslavian film based on the true story of two German sailors executed by fellow POWs on the “fifth day of peace” in May 1945 after being found guilty of cowardice by their erstwhile comrades; reflective and sad music. Il Potere degli Angeli (The Power of the Angels) is a 1988 Italian television film based on Pavel Kohout’s drama Maria’s Struggle with the Angels. The film tells the story of a great theatre actress from Prague driven to suicide by the ‘angels’ – the fantasised embodiment of authority and power – due to her participation in the Prague Spring; gentle and dreamlike music, but ultimately disturbing.

Fragmenta of Mission for cello was composed in 2007 by the cello soloist on this disc, Luca Pincini, from deconstructed themes from The Mission. Unusually, Morricone approved of this composition based on his themes. It’s an effective piece, revealing flashing shards of recognisable themes.

Romanza (for S Fuller) for cello and piano uses music from Les Voleurs de la Nuit (Thieves After Dark), a 1984 French romantic thriller directed by Sam Fuller. Lovely music, not a million miles away from Deborah’s Theme.

Giuseppe Tornatore, his collaborator on films like Nuovo Cinema Paradiso, Legend of 1900 and Malèna, has said of Morricone: “… he is not just a great film composer, he is a great composer”. Are we then any closer to confirming Giuseppe Tornatore’s assertion? No, not really. What is not open to much debate is that Morricone was one of the greatest of film composers. But on this disc we only hear 17 minutes – and 25 minutes on Volume 1 in this series – of music which is not based on ‘applied’ music from films. That’s not really enough to make an informed assessment of the quality of his ‘absolute’ concert music. It does not help either that not much more has been recorded elsewhere.

Based on the quality of his film music, logic would seem to dictate that amongst his 130 concert compositions, including 15 Piano Concertos, a Trumpet Concerto and 8 Concertos for Orchestra, there must be some gems awaiting delving and discovery. It really is time for an enterprising label to do for Morricone what various labels have done for Miklós Rózsa and Nino Rota – bring his concert music to a wider audience. Da Vinci, Chandos and others, please take note and move to your to-do lists.

The Leone Suite contains the most familiar music. However, the sumptuous orchestral versions are not replaced in my considerable affections by these ensemble and solo versions by Morricone himself, fine as they are. In his review of Arcana’s Morricone: Cinema Rarities, my colleague David Barker remarked: “ … I could not escape the feeling … that the original versions of the music, sans violin, were likely to have been a better listening option.” That is my feeling about this disc too. The three excellent soloists perform admirably. The booklet notes by Giovanni D’Alò, as translated from Italian by Chiara Bertoglio and Noelle M Heber, are interesting and informative, and I acknowledge the quotations I have taken from them.

I think the cover artwork could have been more arresting; a line drawing from Matthias Keller’s photograph of Morricone, on a white background, is rather too self-effacing and doesn’t add to the appeal of the package. Although the sound quality of the recording is mostly very good, I do feel that the soloists are perhaps too closely miked, sometimes resulting in an over ‘breathy’ flute, a clangorous piano tone or an over-reverberant cello sound. Apart from these minor reservations, which others may well have no problem with, the disc contains some very fine arrangements; the less familiar film scores and the concert pieces are to be welcomed and are all well worth exploring.

Terry McSweeney

Buying this recording via a link below generates revenue for MWI and helps us keep free access to the site

Contents

Nuovo Cinema Paradiso (Titoli) for piano (1988)

Metti, una sera a cena (“Imagine, an evening having dinner” or Love Circle) for flute and piano (1968)

Rag in frantumi (“Rag in pieces”) for piano (1986)

Bugsy for flute and piano (1991)

Leone Suite for cello and piano:

• Deborah’s Theme (Once Upon a Time in America) (1984)

• Cockeye’s Song (Once Upon a Time in America) (1984)

• Main Theme (Once Upon a Time in America) (1984)

• Once Upon a Time in the West (1968)

• The Ecstasy of Gold (The Good, the Bad and the Ugly) (1966)

Cadenza for flute and magnetic tape (1988)

4 Canzoni for piano:

• Il deserto dei Tartari (The Desert of the Tartars) (1976)

• Le due stagioni della vita (The Two Seasons of Life) (1972)

• Gott mit uns (The Fifth Day of Peace) (1970)

• Il potere degli angeli (The Power of the Angels) (1989)

Fragmenta of Mission for cello (2007) by Luca Pincini from deconstructed themes from The Mission (1986)

Romanza (for S Fuller) for cello and piano from Les Voleurs de la Nuit (The Night Thieves) (1984)