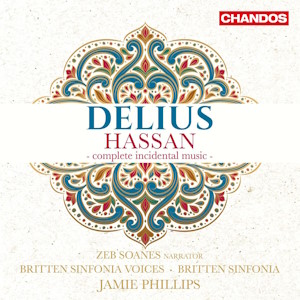

Frederick Delius (1862-1934)

Hassan (1920-1923)

Zeb Soanes (narrator)

Ruari Bowen (tenor)

Frederick Long (bass)

Britten Sinfonia Voices, Britten Sinfonia/Jamie Phillips

rec. live, 11 February 2023, Saffron Hall, Saffron Walden, UK

Chandos CHAN20296 [80]

The name of James Elroy Flecker would be forgotten today were it not for the incidental music written by Frederick Delius to his five act play. Flecker had a career in the British Foreign Service although ill-health and a creative leaning meant he left that post – in part based in Constantinople – to focus on writing. He died in 1915 having just turned thirty with his magnum opus The Story of Hassan of Bagdad and how he came to make the Golden Journey to Samarkand unstaged. World War I and the post-war instability in theatre meant that it was not until 1923 that the London premiere took place.

Delius was first approached in 1920 to provide the incidental music (Ravel had already demurred) – an offer he declined despite having a track record of six operas already written. However he relented when personally visited by the actor/director Basil Dean who ‘sold’ Delius the project. Various further wrangling ensued from the size of the orchestra – Delius wanted a minimum of 30 players but eventually agreed to 26 – to the amount of music required and where it would occur. Initially preludes to each Act and Interludes between scenes were deemed enough but this was significantly expanded to ultimately include underscores and ‘in-scene’ dance and mood music. The final result was a substantial score of around an hour’s music and a further significance is that this was the last major score that Delius physically wrote himself. The advancing syphilis which was to paralyse and blind him – and lead to him working with Eric Fenby as his amanuensis – meant that his wife Jelka helped write some of the music out for him.

The appearance of any new disc devoted to Delius is a cause of celebration. Especially given the recent passing of Sir Andrew Davis who was one of the few established conductors to show a commitment and understanding of this wonderful but elusive music. Conductor Jamie Phillips and the excellent Britten Sinfonia – newcomers to the Chandos artist roster – make a compelling case for the score playing with great skill and sympathy. All the more interesting for the fact that they use a similarly scaled orchestra (24 players) to the 26 of the original production. Unusually for a Chandos disc this is a recording of a live performance – a fact I was blissfully unaware of given the calibre of the engineering and playing until a couple of disembodied ‘noises off’ – most frustratingly a cough during the The Song of the Muezzin at sunset [track 45]- indicated otherwise. Another choice that makes sense given the live/concert context is the inclusion of a role for narrator. Here the sonorous tones of Zeb Soanes make for a very good and engaging story-teller in true One Thousand and One Nights fashion. That said the actual narrative does rather creak for modern sensibilities with the novelty element of the “Mystic East” jarring.

With so much to appreciate and applaud in this new recording it might seem odd not to give it an unqualified reception. This is for the simple reason that the only other complete traversal of the score – by Vernon Handley and the Bournemouth Sinfonietta on EMI – is better. So if the reader has that version in their collection already there is little reason to acquire this one. However, the older version recorded in warm analogue sound as long ago as 1979 in Southampton’s Guildhall, does not appear to be currently in print – I do not think it is a disc that has been reissued since Warner took over the EMI catalogue. If reasonably priced 2nd hand copies can be found – especially in the iteration where it was coupled with Handley’s equally fine Elgar Starlight Express incidental music – then snap it up. Soanes’ presence on this new disc – which in the concert hall must have made for a completely engaging and dramatically effective experience – here becomes tiresome for repeated listening. That despite the effective dramatic distillation of the plot by Meurig Bowen. Yes Chandos has individually tracked the narration and the music so these can be skipped but that does become a bit of a faff. And there is a lot of narration. At first glance the running time of the disc at 80:25 is very generous but of that roughly 22:00 is spoken text (which has been included in full in the booklet). Which means that the musical element is around 58:00. Compare this to Handley who takes just under 63:00 for the exact same music cues. There is one small anomaly between the two performances. Both include the ‘hit’ from the score – Serenade beautifully played as a violin solo by Ronald Thomas for Handley and Thomas Gould for Phillips. But Handley reprises the cue with as a wordless tenor solo three tracks later which does not appear in the new performance. It is such a beautiful piece that it is a shame not to be included. Handley’s tenor is the light and sweet-toned Martyn Hill who is ideal both here and in the previously mentioned The Song of the Muezzin at sunset. Ruairi Bowen for Phillips is good – but simply not as good. Handley’s second singer is another piece of luxury casting – baritone Brian Rayner Cook. I suspect Phillips’ extra impetus is again a question of shaping a performance for a live audience – a logical and intelligent choice. Handley’s generally broader tempi might not be as dramatically apt but are certainly more Delian. Furthermore the Bournemouth Sinfonietta, while still a smallish string section, are bigger than the authentic eleven for the Britten Sinfonia. This extra body of strings, especially when set into the warmth of the Southampton Guildhall does makes for a more sensuous string texture with Handley’s broader tempi just allowing the sense of suspension and rapture to register more tellingly. The Britten Sinfonia players do very well indeed but there are moments when Delius’ frankly ungrateful writing works better with more strings and a slight acoustic haze. That said there is much genuinely beautiful playing from the solo wind of both orchestras.

I find it telling that Delius was originally tasked with just the preludes and interludes. Certainly it is those more extended sections which contain the most atmospheric and characteristic music. Interestingly, the EMI liner relates Basil Dean being enraptured by Delius’ music when hearing a performance of A Village Romeo and Juliet at Covent Garden in 1920. Many of the Delius musical fingerprints are present in Hassan with the Preludes to Acts III-V especially atmospheric. Likewise the fairly extensive use of an off-stage chorus is a typical but effective Delian musical device. Another highlight in both recordings is the closing scene when the caravan takes the two main characters away from Bagdad. This echoes many of Delius’s recurring musical and emotional tropes of transience and farewell so no real surprise it should have found such resonance for the composer. For me the less interesting or successful parts of the score are those that directly interact with the action – so the group of dances for the beggars in Act II, the fanfares for the Caliph or the War Song of the Saracens simply do not play to Delius’ strengths – he is rarely a ‘literal’ or illustrative composer – and his attempts at local colour are rather weak. The notable exception is the stark The Procession of Protracted Death which is quite unlike any other Delius I can think of and actually very effective.

Nobody encountering this score for the first time through this version will be disappointed as there is much music and performing skill to be enjoyed and admired. But conversely I think there is little doubt that the Handley version is preferable.

Nick Barnard

Previous review: Paul Corfield Godfrey (May 2024 Recording of the Month)

Buying this recording via a link below generates revenue for MWI, which helps the site remain free.