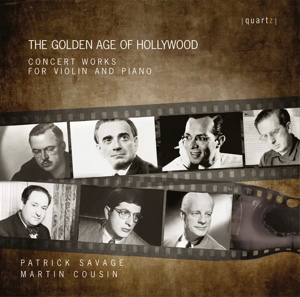

The Golden Age of Hollywood: Concert Works For Violin and Piano

Patrick Savage (violin), Martin Cousin (piano)

Recording details not supplied

Reviewed as MP3 download

Quartz QTZ2156 [62]

The title is a little misleading, insofar as the programme doesn’t include a single piece of film music. On the other hand, all the composers represented had important careers as film music composers but also had ambitions to write art music, which in some camps was not compatible with the cheap commercial film scores. All these composers were eminent craftsmen in both functions, however, and were appreciated by the likes of master violinist Jascha Heifetz. For example, he premiered Korngold’s violin concerto, written several years after his Hollywood career was over. He even recycled several themes from his film scores which got a new lease of life in this concerto, which during the last few decades has become part of the standard repertoire. “More corn than gold” was once a popular condemnation of Korngold’s concerto, but those days are long gone.

The four-movement suite from the incidental music for Max Reinhardt’s Vienna production of Shakespeare’s Much Ado About Nothing is much earlier, in fact the earliest music in this programme – and also the best-known. Composed in 1920 by the one-time Wunderkind, who stunned both Gustav Mahler and Richard Strauss before he even was ten, we here find him in his early maturity at age 23. Here he was already a celebrity and within a couple of years was to conquer the world with his opera Die tote Stadt. His melodic genius was already fully developed, and who can resist the yearning sweetness of the first movement – warmly played with beautiful tone? Korngold at his most romantic. The third movement, Garden Scene, is in the same vein. Sentimental? Certainly, but not over-sugary, and truly enticing. In between comes March of the Watch, sprightly and distinct with a swagger and a humorous glint in the eye. The concluding hornpipe titled Masquerade, is a marvellous playful pastiche. This is music to which I joyfully return – and have done ever since I heard the orchestral suite – which also includes an overture – on an EMI LP issued in 1974, coupled with Ulf Hoelscher’s recording of the violin concerto. That was one of first issues in the Korngold renaissance, issued the year before Leinsdorf’s recording of Die tote Stadt.

Franz Waxman, another Jewish émigré from German-speaking Europe, had an important career in the US, both as film composer – Rebecca, Sunset Boulevard, A Place in the Sun – and conductor. In 1948 he composed Four Scenes of Childhood as a present to his good friend Jascha Heifetz on the birth of his son. Unfortunately Heifetz never recorded it, and the manuscript didn’t surface until after Heifetz’ death, when it was found among his sheet music. This is charming, idyllic, easy-going music, and the titles of the four movements are self-explanatory. It opens in the piano with chimes of a clock; the Promenade is light-hearted; Playtime is bubbling over with high-spirits and Bedtime Story is an easily rocking lullaby.

Robert Russell Bennett is best known as a masterly orchestrator on Broadway, and won an Academy Award for his orchestral score of Rodgers and Hammerstein’s Oklahoma. His Hexapoda from 1940 is inspired by various jazz-influenced dances, including the jitterbug, and was a great success at the premiere, when it was played by Jascha Heifetz. The New York Herald Tribune wrote about the five movements: “…they are evocative of swing music without themselves being swing music…They are, in addition, magnificently written for the violin.” The whole suite is a real vitamin injection, and I wouldn’t be surprised if after enjoying it readers reprised it immediately – as I did.

Heinz Roemheld (1901 – 1985) is supposedly the least know of these seven composers, but he was a prolific deliverer of film scores and concert music. A child prodigy on piano he composed challengingly for his instrument, but for Martin Cousin that doesn’t pose any problems. The sonata in three movements from 1950 is the most recent work in this programme. The first movement has, like Russell Bennett’s Hexapoda, influences from jazz, but also from Les Six, and the movement culminates in an intricate fugato section that ends abruptly. The second movement is to be played Sempre senza vibrato, i.e. without vibrato throughout. The effect is the sound of a beginner, playing a simple theme over and over again, while the piano part becomes more and more complicated and harmonically wilder and wilder. The violin catches up in the “Very fast” final movement, where both instruments challenge each other to virtuoso playing of the highest order. A brief return of the theme from the second movement temporarily halts the proceedings, but then it’s back to business again. This is truly invigorating playing again. This is another piece worth a second hearing without delay.

Jeremy Moross became one of the most influential creators of music for Western films, epitomized in the Oscar-nominated score for The Big Country in 1958. His Recitative and Aria for Violin and Piano was written much earlier, in 1941, but here again cowboys are present, pointing forward to open prairie – but there are also deeply lyrical portions here.

Bernard Herrmann won an Academy Award for the score to The Devil and Daniel Webster in 1941, but is best known for his many scores for Alfred Hitchcock during the 1950s and 1960s. His Pastorale, which here gets its first recording , was composed as early as 1929, when he was a tender late teenager. Considering the harsh harmonies in his mature film scores, this is a surprisingly mild work, impressionistic and beautiful. The same year, four years older Miklós Rózsa composed his Variations on a Hungarian Peasant Song. He was strongly influenced by his compatriot Béla Bartók and also by Hungarian folk music. This of course is very obvious in this work. What is also obvious is that Rózsa was a professional violinist himself. He knew exactly what a skilled violin player could be expected to manage, and this is highly virtuosic music but also music filled with lyricism.

Patrick Savage and Martin Cousin play with impressive assurance in a programme that is filled with challenges. The programme per se is also highly fascinating; apart from the Korngold work a lot of the music is little-known, and I am sure many readers of this review will discover a lot that, hopefully, will be dear friends for years to come.

Göran Forsling

Buying this recording via a link below generates revenue for MWI, which helps the site remain free.

Contents

Erich Korngold

Suite from Much Ado About Nothing Op.11

Franz Waxman

Four Scenes of Childhood

Robert Russell Bennett

Hexapoda: Five Studies in Jitteroptera

Heinz Roemheld

Sonatina for Violin and Piano

Jerome Moross

Recitative and Aria for Violin and Piano

Bernard Herrmann

Pastoral (Twilight)

Miklós Rózsa

Variations on a Hungarian Peasant Song