Déjà Review: this review was first published in May 2005 and the recording is still available.

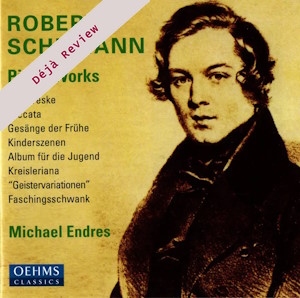

Robert Schumann (1810-1856)

Humoreske Op. 20 (1838)

Toccata Op. 7 (1829-32)

Gesänge der Frühe Op. 133 (1853)

Kinderszenen Op. 15 (1838)

Album für die Jugend Op. 68 (1848)

Kreisleriana Op. 16 (1838)

Theme with Variations in E flat major WoO 24 (‘Geistervariationen’) (1854)

Faschingsschwank aus Wien Op. 26 (1839-40)

Michael Endres (piano)

rec. Cologne, 2000/01

Oehms Classics OC366 [3 CDs: 209]

Michael Endres is a superb pianist of integrity who clearly loves his Schumann. If you are coming to terms with the composer’s solo piano music for the first time, this triple disc set will get you off to more than a good start. Should you already have a patchy collection, this could be a splendid way to plug a few gaps. Even seasoned connoisseurs may wish to own the CDs for the performances, in spite of the fact that some of the greatest of pianists have recorded these works.

The chosen items represent all aspects of Schumann’s solo keyboard work. There is the youthful, virtuosic Toccata, the shortest piece here, as well as the most extensive work Schumann wrote, the Album für die Jugend which takes up the whole of disc 2. And there is a work from the end of his life, the Theme with Variations in E flat, a tragic swansong if ever there was one. Schumann wrote down the melody, which he said the angels had dictated to him, when in the grip of mental illness. Just over a week later he had completed the work, and while in the middle of making a fair copy, ran out of his home and threw himself into the Rhine. He was fished out and died in an asylum two and a half years later, not long after his forty-sixth birthday.

Early in disc 1 we can hear examples of music that illustrate the stylistic range of Schumann’s piano work. The Toccata is, by Michael Endres’ own admission in the booklet notes, “stupendously difficult”. On hearing it we can tell that the pianist is indeed a virtuoso but that he is not prepared to turn pieces such as this into vehicles of pianistic display (some would and do, e.g. Argerich and Horowitz). That is what I meant when I said he was a pianist if integrity (I am not necessarily implying that Argerich and Horowitz are without integrity!). Before that, the disc had opened with Humoreske‘s wistful first number and Endres plays it with great beauty. He does take this kind of movement quite slow – often slower than most – but avoids overdoing the romanticism with manneristic rubato. The contrasting third movement of the piece has a furious left hand part. Now you cannot play Schumann without a strong left hand. It was a special quality said to have been possessed by Schumann’s wife, the great pianist Clara Wieck. One aspect of Schumann’s style is the tension generated by seemingly contradictory things going on between right and left hand. This can take the form of conflicting cross-rhythms. At other times it can be that the right hand is playing a lyrical melody while the left indulges in rapid, hair-raising passage work. To pull that off you need not only to play the notes in the left hand accurately, but keep them fluid and dynamically suppressed in order to maintain the substantive mood generated by the right hand. One of the supreme exponents of this technique was Sviatoslav Richter. A good example of music that requires such interpretation is the Intermezzo from the last work in the set, Faschingsschwank aus Wien. I compared a 1962 recording of Richter with Endres. To my astonishment, not only did I find Endres going slightly faster but competing quite happily with Richter, maintaining a silken lyricism and even sounding more secure (to be fair to Richter, his was a live performance). Richter does have his extra special charisma shining through – but whether that is what the piece needs is another matter.

Of course, with piano playing of old favourites, there is the matter of personal taste. For example, I have always thought of Kinderszenen as a collection of musical fairy tales and I like them told straight with some evocation of childhood innocence. Endres does indulge a little romantic rubato that sounds too grown up for me. But then Schumann did say the pieces were “grown-up memories for grown-ups”. There are tiny mannerisms that you would expect from any pianist which some people will like, others not so much. For example Endres sometimes fractionally holds before a strong beat.

These things are trifling in the context of the whole set which I think a major recording achievement. I have no hesitation in recommending these CDs to any of those three categories of listener I referred to in my first paragraph.

John Leeman

Buying this recording via a link below generates revenue for MWI, which helps the site remain free