Déjà Review: this review was first published in May 2005 and the recording is still available.

Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart (1756-1791)

Don Giovanni, Dramma giocoso in two acts, K. 527

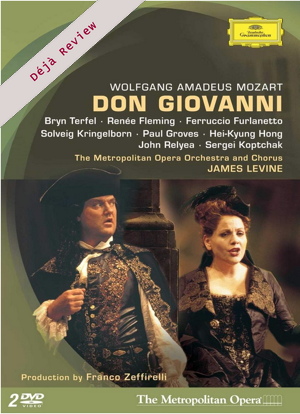

Don Giovanni, Bryn Terfel (baritone)

Leporello, Ferruccio Furlanetto (bass)

Don Ottavio, Paul Groves (tenor)

Masetto, John Relyea (baritone)

Anna, Renée Fleming (soprano)

Elvira, Solveig Kringelborn (soprano)

Zerlina, Hei-Kyung Hong (soprano)

Commendatore, Sergei Koptchak (bass)

Metropolitan Opera Chorus & Orchestra/James Levine

Stage director: Stephen Lawless

rec. 2000, Metropolitan Opera, New York, USA

Deutsche Grammophon 0734010 DVD [2 discs: 180]

By 1785 Mozart had moved from Salzburg to Vienna via Munich. He did this so as to enlarge his opportunities. By then his strengths as an opera composer were widely recognised and the genre was to remain central to his ambitions. In 1786 he commenced collaboration with the poet Da Ponte to realise the immensely popular Le Nozze de Figaro with its taut plot and integrated music. The work was immediately widely acclaimed and was later produced in Prague with unprecedented success. Bondi, the Manager of The Prague Opera, keen to capitalise on Mozart’s popularity in the city, commissioned a new opera from him for production the following autumn. Mozart returned to Vienna and sought the cooperation of Da Ponte for the provision of a suitable libretto. Although Da Ponte was working on librettos for two other composers he agreed to set the verses of Don Giovanni. It is suggested that Da Ponte used some existing material.

Don Giovanni was well received in Prague. However, for a production in Vienna the following year there were problems. The tenor couldn’t sing his Act 2 aria Il Mio Tesoro and Mozart substituted the aria Dalla sua pace, better suited to his abilities, at No.10 in Act 1. The role of Elvira was to be sung in Vienna by a protégée of Salieri; she demanded a scena for herself. Mozart added the accompanied recitative In quali eccessi and aria Mi Tradi at No.26. Common performance and recorded custom is to incorporate the later Vienna additions into the Prague original. This practice is followed here. However, perhaps as a result of the origins of the libretto added to the insertions of the Vienna scenes, a performance can sometimes seem a hotch-potch and dramatic cohesion is lost. The production scenery needs to be capable of quick change from one often-short scene to the next, whilst the producer needs to accommodate the intimate with the more public group situations.

The sets and costumes in this production situate the work in the period of its composition. The sets move swiftly and easily, and with the additional help of backdrop, convincingly accommodate the various settings. I was not, however, impressed with the finale as Don Giovanni sings of being surrounded by fire as the Commendatore draws him down to hell. This provides an opportunity for a veritable coup de théâtre. The opportunity is missed in this production. Or maybe the persistent use of close-ups by the video director threw the baby out with the bathwater. I am sure that if Brian Large, who has been responsible for the video direction of over seventy Met performances had been in charge, a better visual balance would have been achieved. There is also, in my view, a major incongruity in the costumes. Masetto and Zerlina are described as country folks or peasants. In this production their dress is indistinguishable from the aristocrats who play the other roles.

Of course the singer who plays Don Giovanni carries the greatest burden histrionically and vocally. In Chicago in September 2004 Bryn Terfel, in a production by Peter Stein, said farewell to the role as he prepared for Wagner’s Wotan at London’s Covent Garden. A wise decision; Mozart and Wagner mix on a voice much as hot fat and water in a pan. He has been the non-pareil Don Giovanni de nos jours and his sung and portrayed performance in this production illustrates his strengths to the full. He is vocally mellifluous in his aria Finch’han dal vino (D1. Ch. 27) and serenata Deh vieni alla finestra (D2, Ch. 5) and his caressing of the phrases as he persuades Zerlina to go with him in La ci darem la mano (D1 Ch. 16) is a delight. But the role of Don Giovanni is about more than singing and here Bryn Terfel excels in his portrayal of the sadistic pursuer of women. His physicality, facial expression, verbal nuance and acting, constitute a portrayal of Don Giovanni as a sadistic rake who will pursue his carnal pleasures by persuasion or force, preferably the latter. His derision on Donna Elvira as she tries to persuade him to change his lifestyle is chillingly sardonic (D2 Ch. 25). Terfel’s sadistic portrayal is also illustrated by his physical dominance and treatment of Leporello sung by Ferruccio Furlanetto. A native Italian he relishes the many recitatives whilst the Catalogue Aria flows from his tongue with relish (D1 Ch. 10). Throughout his acting is of the highest order as he alternately fears his master or, after a suitable bribe, manoeuvres to facilitate the next seduction or rape.

As Donna Anna, the opera’s first victim of Don Giovanni’s amorous intentions, Renée Fleming sings ravishingly with a wide palette of vocal colour. This is evident over the whole range of her wide range and particularly in the higher tessitura where so many sopranos are found wanting. Her rendering of the recit and aria Non mi dir (D2 Chs. 21-23) is a vocal highlight of the performance. Miss Fleming’s acting conveys both the vulnerability and steely resolve of Donna Anna although she cannot overcome the directors rather clumsy managing of the first scene when Don Giovanni emerges from her bedroom. Paul Groves as her betrothed sings the two tenor arias in this combined version with elegant phrasing and a nice balance between heady tone and steely resolve (D1 Ch. 25 and D2 Ch. 15). He manages to appear less of a wimp than is often the case. Solveig Kringelborn convincingly portrays the lovelorn Donna Elvira. Her whiter tone is distinctly different than Fleming’s and lacks some vocal colour. Nonetheless her singing and acting, particularly her facial expressions, convey the emotionally tortured and mixed up Donna Elvira. Her rendering of the recit and aria Mi tradi, added for Vienna, was well received but not ideally steady across the range (D2 Chs. 16-17). Donna Elvira’s parading across the stage in the final scene carrying an opened parasol was another of the producer’s less felicitous ideas. The Zerlina of Hei-Kyung Hong is convincingly acted and sung. Her lyric soprano is flexible and expressive and with a pleasing richness of tone making her Batti, batti o bel Masetto another vocal delight (D1 Ch. 29). As her nearly cuckolded lover Masetto, John Relyea’s acting and facial expressions have more variety than his firm toned and well tuned singing.

James Levine’s Mozart has no great distinction. He moves the music along without seeking to convey anything of the evolving drama. He is content to support the breathing and phrasing of his singers and is careful not to drown their voices. These are considerable virtues. They are preferable to maestri who pull Mozart’s carefully considered tempi around and also allow the words to be heard throughout a 4000-seat auditorium, particularly when the diction of all the singers in this performance is of a standard too often lacking. I am sure Peter Stein’s production in Chicago will have had many more considered and illuminating moments than are found here. It too was superbly cast. As well as featuring Terfel’s farewell to the role of Don Giovanni, Karita Mattila was singing her last Donna Anna whilst Susan Graham was dipping her toes into the waters of the soprano fach for the first time as Donna Elvira. That production may appear on DVD. In the meantime, this well sung performance in traditional sets and costumes will meet most needs and provide much enjoyment.

Robert J Farr

Buying this recording via a link below generates revenue for MWI, which helps the site remain free.

Other details

Production and set design, Franco Zeffirelli

Costume design, Anna Anni

Lighting design, Wayne Chouinard

Video Director, Gary Halvorson