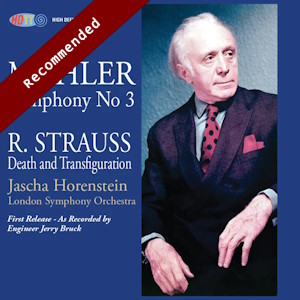

Gustav Mahler (1860-1911)

Symphony No. 3 in D minor (1895)

Richard Strauss (1864-1949)

Tod und Verklärung Op.24 (1888/89)

Norma Proctor (contralto)

Denis Wick (trombone), William Lang (flügelhorn)

Ambrosian Singers, Wandsworth School Boys’ Choir

London Symphony Orchestra/Jascha Horenstein

rec. 27-29 July 1970, Fairfield Halls, Croydon, UK

High Definition Tape Transfers HDTT15476 [2 CDs: 120]

Jascha Horenstein’s recording of Mahler’s Third, made for Unicorn-Kanchana between 27 and 29 July 1970, has been one of my go-to versions of this great symphony for as long as I can remember. I reviewed it, somewhat belatedly, back in 2016, though it had already been around in CD form – and I had owned it – for a good number of years by then. I have more versions of Mahler’s Third in my collection than probably is good for me. The ones that I rate particularly highly include those conducted by Abbado (his first recording, for DG, with the Chicago Symphony); Levine (RCA, also with the Chicago orchestra); and Mitropoulos’s flawed but compelling live account (review). Three recordings stand out from the crowd, though, one of which is this present one conducted by Jascha Horenstein, which I esteem as highly as my other two favourite recordings, by Bernstein and Tennstedt. Horenstein’s interpretation may not quite match the flamboyance (especially in the first movement) of Bernstein’s marvellous first recording of the work, made for CBS – now Sony (review) – or the sheer intensity of Tennstedt’s live 1985 account (review). However, there’s an honesty and directness about Horenstein’s way with the score that I find compelling from start to finish. It has been highly regarded ever since it was first released, and rightly so.

Now HDTT have released the Horenstein recording, but this is not a reissue and/or remastering of the Unicorn release. What we have here is the same performance but it’s not the same Bob Auger-engineered recording. Nick Barnard explained the somewhat unusual circumstances in his very detailed and enthusiastic recent review of the HDTT set. Two different recordings were made in parallel; as Nick described it, “[u]nusually, John Goldsmith [the general manager of Unicorn], gave American sound engineer and Mahler aficionado Jerry Bruck permission – at his own expense and using his own equipment – to set up a quite separate and independent recording rig to record those same sessions in parallel with the ‘official’ rig. Quite why Goldsmith did this is not clear”. You’ll find much more detail about the techniques which Bruck used, and how these differed from Auger’s approach, in Nick’s review, so I won’t repeat what he has already explained so well. Jerry Bruck’s recording was not a closely guarded secret; it was known about, but the tapes were never edited or prepared for commercial release. Now, more than 50 years after those sessions in the Fairfield Halls, Croydon, Jerry Bruck has given HDTT permission to issue his recording commercially.

I’m going to talk about the performance first, before I come on to the recorded sound. In truth, though, not a vast amount of comment is needed: this is one of the great Mahler performances; Horenstein’s magnificent interpretation is superbly played by the LSO. I went into more detail about the performance itself in my aforementioned review of the Unicorn set. It was also discussed fully and with admiration by Tony Duggan in his survey of recordings of the symphony. Tony concluded his appraisal thus: “This remains one of the greatest recordings of any Mahler symphony ever set down and I think it always will”. I concur. The huge first movement is superbly unfolded by Horenstein. No detail, it seems, escapes his eye (and ear). True, he may not bring to certain episodes the swagger that Bernstein achieves, but Horenstein is never less than exciting; everything seems right. Dennis Wick plays the crucial trombone solos in a commanding fashion. Horenstein exhibits consistent focus and lets the music off its leash just enough while maintaining close control. To the Tempo di Menietto second movement he and the LSO bring a delightful lightness of touch. He paces the music beautifully and with affection; one is conscious of an expert Mahler stylist at work. At the start of the third movement and, indeed, throughout it, I love the perky playing of the LSO woodwinds. The nostalgic posthorn episodes, played by William Lang on a flügelhorn, are expertly judged both by the conductor and the engineers; Lang’s playing is a delight. Norma Proctor’s voice is ideally suited to the fourth movement. She, Horenstein and the orchestra convey the dark timbres and ambience of this music very convincingly. Proctor also makes a fine if brief contribution to the fifth movement; hereabouts the crispness of the choral singing – and the playing – make a good impression. The long, expansive finale crowns this performance. In the opening pages the LSO strings offer distinguished, eloquent playing and Horenstein paces the music in an ideal fashion. Throughout the 22:56 span of this movement he is unfailingly patient, taking the long view. He builds the movement expertly and his patience is rewarded every time a climax arrives. He prepares for each of them expertly and then in the climaxes he achieves genuine grandeur, for example at around 12:00. At 16:22 the trumpet chorale leads the ascent to the final peroration; these last few minutes are unforced, broad and majestic. This deeply satisfying account of Mahler’s finale sets the seal on an unforgettable performance of the symphony.

So, here we have a performance of great distinction: what does it sound like in this new HDTT incarnation? Well, in a word (or two), highly impressive. When I sampled this recording with colleagues in the MusicWeb Listening Studio in April 2024, we did a ‘blind’ testing of the HDTT discs and the original Unicorn release. I reported that we noted a slight edge to the sound of some instruments in the Jerry Bruck recording, though we certainly didn’t use the word ‘edge’ in an uncomplimentary sense. Subsequently, I have been able to do much more detailed listening on my own equipment, doing A/B comparisons between the two recordings. Initially I again noticed the slight edge on the Bruck recording, though this wasn’t unwelcome; however, I soon became far less aware of the edge as my ears adjusted. One factor intrigued me, though. On the Studio equipment, where we played the discs without altering any of the controls, we felt the Auger recording was louder; on my own equipment the reverse was the case.

I should mention that I have experienced this release via the conventional stereo version rather that the High-Res version which is available as a download option and which I bet is spectacular. I listened through both my Monitor Audio loudspeakers and through my Beyerdynamic DTS Pro headphones. I liked the sound of both the Auger/Unicorn and Bruck/HDTT discs when played through the loudspeakers; but when I switched to headphones, I had a decided preference for the Bruck sound. Both engineers produced excellent, well detailed recordings but I came to feel that Bruck had achieved a degree more definition and presence. His recording has an excellent dynamic range, something which is very important in this symphony. I think there’s a degree more warmth in the Auger/Unicorn sound but the Bruck/HDTT sound has greater impact. All that said, I think the differences are not so great that I would advise anyone who already has the Unicorn discs to rush out and trade up to HDTT. On the other hand, if you have the Unicorn, I’d recommend that you at least try the HDTT. If you haven’t got this legendary recording in your collection then the HDTT issue is the one to go for.

In the Listening Studio our sampling was, of necessity far more limited than I’ve since been able to do. We reached the conclusion that “our preference was for the Unicorn original but we all felt that both recordings have much to offer. Jerry Bruck’s recording doesn’t supersede the work of Bob Auger but offers a different – and very stimulating – alternative experience.” As you may have gathered, I’ve now reached the reverse preference but I still adhere to our final observation that the work of each sound engineer offers a different, complementary listening experience. Whichever recording you come to prefer, I think one conclusion is inescapable. Working with different recording rigs – and, dare I suggest, different engineering philosophies – Bob Auger and Jerry Bruck each achieved stunning results. Both engineers produced extraordinarily fine analogue recordings and captured this huge orchestra and Mahler’s complex scoring in a way that is frankly breathtaking. I found that both engineers give us a fine reproduction of the orchestra, from the deep, firm bass registers to the highest treble frequencies. In both recordings the percussion sounds thrilling but I think perhaps Bruck has the edge in the way those instruments are experienced. One other point of detail is worth mentioning. In the third movement, the Bruck recording makes the solo flügelhorn more present. Some may prefer the more distanced sound on the Auger recording but what Bruck does is to make us more aware of the nostalgic, mellow sweetness of William Lang’s instrument. And even if Bruck’s sound is a bit more present – and we’re talking fine margins here – there’s no diminution of the poetry of this episode. Listening to either version you would struggle to believe that these recordings were made in 1970. Sadly, it appears from what Misha Horenstein has to say in the booklet that Bob Auger’s original tapes have been lost so there is no chance of them being remastered using today’s technology.

In comparing these two recordings I’ve been listening to Unicorn CDs that were released in 1988. For HDTT, Jerry Bruck’s tapes were transferred at 24/192 kHz in late 2020 by Robert Wirak; the tapes were then edited and restored between 2020 and 2024 by John Haley (except that Bruck’s own 1970 edit of the third movement tapes was used). The HDTT restoration work has been first class.

HDTT’s set is completed by a substantial bonus in the shape of Tod und Verklärung. In July 1970, Horenstein and the LSO had six three-hour sessions available to them; remarkably, they managed to complete not just the vast Mahler symphony but also this Strauss tone poem in that time. The conductor’s cousin, Misha Horenstein, who has been keeper of the flame for many years and to whom we owe the release of so many live performances by Jascha Horensteinover the years, relates in the booklet that the Strauss recording was made in the sixth and last of those sessions. He also shares some interesting details about how the recording was made despite Musicians Union time constraints. Apparently, Horenstein customarily took around 24 minutes to play this piece but the present performance comes in at 22:02. Having noted that, I got no sense of undue haste in the music making; though there is dramatic thrust in the agitated section that begins at 4:13, I’d expect nothing less. Elsewhere, the opening is beautifully paced and detailed, while the apotheosis of the Transfiguration theme (from 17:26) has genuine grandeur. The LSO executes Horenstein’s vision of the piece marvellously and I’d sum this up as a very fine performance of which Jerry Bruck gave us an equally fine recording. Apparently, the LSO’s Union representative turned a blind eye to the time overrun in the session. How wise he was to exercise flexibility; those of us who listen to this performance owe him a debt of gratitude.

HDTT have documented their release well. The booklet includes an extended essay by John Haley in which he discusses the background to the recording and explains the recording techniques that Jerry Bruck used. In a separate note there’s an appreciation of Bruck as both a sound engineer and Mahler aficionado. In addition, Jascha Horenstein’s cousin, Misha contributes an essay in which he pays a generous tribute to the founder of Unicorn, John Goldsmith (1939-2020), in the course of which he gives some fascinating information about these recording sessions. To complete the booklet there’s a brief biography of the conductor.

I shan’t be sending my copy of the Unicorn CDs to a charity shop; that would be deeply disrespectful to what remains a very fine recording. However, I’m delighted to have this alternative recording of the same performance in my collection. Jerry Bruck did a wonderful job in preserving the results of those three memorable days in July 1970 and it’s very pleasing that thanks to HDTT his work will now receive the circulation and recognition it deserves,

John Quinn

Previous review: Nick Barnard (March 2024 Recording of the Month)

Availability: High Definition Tape Transfers