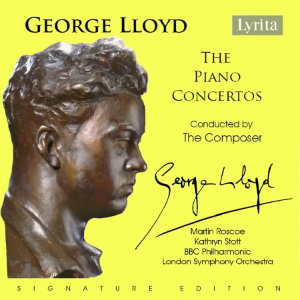

George Lloyd (1913-1998)

‘Scapegoat’ (Piano Concerto No.1) (1963)

Piano Concerto No.2 (1965)

Piano Concerto No.3 (1968)

Piano Concerto No.4 (1970)

Martin Roscoe (piano: 1 & 2), Kathryn Stott (piano: 3 & 4)

BBC Philharmonic Orchestra/George Lloyd

rec. 1988-90, New Broadcasting House, Manchester (1-3) and February 1984, Henry Wood Hall, London (4)

Lyrita SRCD2421 [2 CDs: 143]

After the first two symphonic boxes, the 8 CDs of which restored George Lloyd’s legacy in handy form, the next release is a twofer devoted to the four piano concertos. The cycle occupied him from 1963 to 1970, begun shortly after Symphony No.8 had been written and completed very soon before he composed Symphony No.9.

As Paul Conway relates in his booklet notes, Lloyd was not in good mental health at the beginning of the 1960s and these concertos offered him a new direction, urged on as he was by his wife, Nancy. Concerto No.1 ‘Scapegoat’ was written for John Ogdon and is a single-movement 25-minute work of very defined sectionality. Its opening is orchestrally jagged, countered by the piano’s conciliatory, reflective statements which are subject to mocking orchestral interruptions, notably from the winds. This terseness, the agitation of which dissipates in the second section with evanescent warmth, finally turns genial in the work’s central section. The Scherzando is the heart of the work, geographically speaking, and negotiates the twin extremes of Lloyd’s troubled mind, as the vehemence soon redoubles, an eruptive force that has barely been concealed. It leads eventually to the final section, a five-minute panel that functions as a just expressive summation of the work.

Lloyd had been a violinist in his youth and was only really reconciled to the validity of the piano concerto through ‘Scapegoat’ but once it had been written he was soon at work on Piano Concerto 2, which followed two years later. It, too, is sectional and cast in a single movement, and was premiered by Martin Roscoe in 1984. Whether its original impetus was the ‘Hitler Jig’ – the dance Hitler was alleged to have done when he received the news of the fall of France – the music is surprisingly sinister with an insidious, scampering quality from the piano allied to athletic demands. It has a helter-skelter quality that conveys a decidedly uneasy mood. Lloyd’s use of the percussion was, symphonically, always inventive and colourful and so it proves in the second panel of this concerto. Its March themes are distinctive – they never remind one of, say, Prokofiev – but some of the piano chording sounds strongly Rachmaninovian and the move into the third section might suggest Nielsen. The deft slow section has something of Ravel’s stillness and simplicity about it, the orchestra gradually building up to the final section with its melancholy songfulness, with increasing ebullience. In this concerto Lloyd builds material from cell-like material and it’s remarkable how his super-structures prove to be aggregates of these small motivic elements.

The Third Concerto of 1968 is his biggest, lasting 48 minutes and cast in three conventional movements. The opening is, this time, decidedly Prokofiev-like though cross-pollinated with some aromatic Gallic influences. Though there are, as so often in Lloyd’s music, military and fanfare allusions in the brass and exciting percussive writing, the mood is neo-romantic and fulsome, and the piano writing somewhat playful. The very long central slow movement – it’s nearly 20 minutes long – is laced with deft runs and a sense of atmosphere that courts almost dreamlike stasis. When the dynamic contrasts arrive it’s with a vehemence that contrasts with limpid refinement, almost hallucinatory in effect. More military brass calls are reprised by the winds, which allows a jaunty March to emerge. At which point the piano begins a nostalgic song. It’s quite remarkable, as Conway says, how Lloyd sustains his material over such a period of time. The finale starts brightly and tautly, those military calls converted here to a more jaunty, jocular mood. The piano is a puckish actor, oscillating between dreamlike reverie and playfulness. It’s a fine concerto though, in my view, judicious pruning wouldn’t have harmed it as, from time to time, there’s a feeling of huffing and puffing.

My own favourite happens to be No. 4, at which I was at the premiere performance. In this 1970 concerto, at the apex of his accommodation with the form, Lloyd fuses vocalised melodies – he always remained an operatic composer in symphonies and concerted works – with a firm, defined sense of form. Influences can be felt, inheritances that operate throughout his symphonic canon, but they are lightly borne. It’s the Strauss of Till Eulenspiegel that appears occasionally in the first movement, as Lloyd’s quirky, rhythmic patterns begin. The piano’s ruminative entrance and beautiful vocally-conceived melodic richness inspires a comparable orchestral response, which has a kind of Rachmaninovian lyricism. As the movement draws to a close the winds are interrupted by the perky spirit of the opening figures, in a satisfying sense of symmetry. The piano is no virtuoso in this work – in truth Lloyd seldom makes virtuoso demands – rather it offers a sense of colour and dappled elegance, quietly memorable in such a way as to arrest time, as happens in the Larghetto. The finale offers one of Lloyd’s most catchy, snappy conclusions. The orchestral writing is clean-limbed, and in the Lento section at the heart of the finale, there’s yet another of those unfolding lyric themes of great beauty. Then we get a brassy, bold resumption of the hi-jinks, with a salty Latin twinge thrown in here and there. This is a memorable work, for me. Its thematic writing is elevated, it’s not too long, it pays its dues and it delivers on all fronts. I may be wrong about this, but at the time of its premiere I don’t remember it receiving altogether favourable reviews. Well, that was 40 years ago and we can see things more clearly now.

Martin Roscoe is the protagonist in Concertos 1 and 3, Kathryn Stott in 2 and 4. The BBC Philharmonic accompanies in all but No.4, where it’s the LSO. Lloyd conducts throughout. The concertos are reissued in this Signature Edition in a slimline twofer and lovers of Lloyd’s music will be delighted to know they’re available in this compact form.

Jonathan Woolf

If you purchase this recording using a link below, it generates revenue for MWI and helps us maintain free access to the site