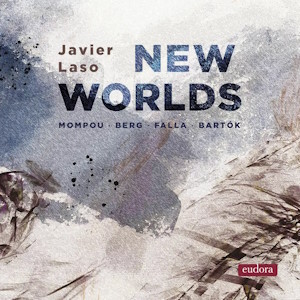

New Worlds

Frederic Mompou (1893-1987)

Variations on a Theme of Chopin (1957)

Alban Berg (1885-1935)

Piano Sonata, Op.1 (1908)

Manuel de Falla (1876-1946)

Fantasia Baetica (1919)

Béla Bartók (1881-1946)

Piano Sonata, Sz.80 (1926)

Javier Laso (piano)

rec. 2022, Auditorio de Zaragoza, Sala Mozart, Zaragoza, Spain

Eudora EUDDR2402 SACD [66]

Spanish composer Frederic Mompou’s remarkable Variations on a Theme of Chopin were devised for cello and piano but never completed. Mompou then penned four variations for piano, which were issued. Later, the Royal Ballet approached him in 1957 to produce a dance score. He finished all twelve variations. The ballet was never performed, but the music was duly published.

The Variations are based on Chopin’s Prelude in A major, Op.28 No.7. The booklet sums up their effect: “[They] present an extreme diversity of styles and moods, including sumptuous art déco harmonies; airy reveries; gentle Mediterranean echoes of Poulenc’s pianism; more intimate, personal visions alluding to sonorities from earlier Mompou works; undisguised tributes that stick closely to the Chopinian model; and moments of passionate virtuosity.” Echoes of Fauré, Satie and the “impressionists” can also be heard in these pages. This beautiful work is played here with a magical touch.

The time of the composition is a surprise. Much was happening in the mid-nineteen-fifties, and the boundaries of music were pushed to a huge extent. Think Boulez, Stockhausen, Berio and Xenakis. Yet here was a composer who wrote in an elusive, meditative and evocative manner at least fifty years out of date.

Alban Berg’s Piano Sonata crosses several boundaries of musical aesthetic. It looks back to Lisztian and Wagnerian chromaticism. It also looks forward to the extended atonality that was to become a feature of his music. Using thematic transformation and developing variation, the single movement gradually unfolds. There are all the appurtenances of classic sonata allegro form: exposition, development and recapitulation. The work is written in B minor, but the tonality is fluid, with abundant chromaticism and some whole-tone scales.

It is known that Berg intended the Sonata to have three movements, but he was unable to finish it. On the advice of Arnold Schönberg, he published the first movement as a standalone piece.

Javier Laso’s spellbinding performance undoubtedly reveals Berg’s argument. It emphasises the exploration of the thematic fragments developed from the opening bars. The varying emotions are well defined. Passion and repose are perfectly balanced.

Manuel de Falla’s Fantasia Baetica was his last major work for the piano. (There was a small contribution to the multi-authored Homage à Dukas, published in 1935.) It presents a “characteristically Andalusian manner”. Criticism over the years has tended to suggest that the Fantasia should be shortened, and cuts have been recommended. Yet what to cut? I think that removing any bars would destroy this wonderful evocation of Spain.

Polish pianist Artur Rubinstein commissioned the piece and reputedly premiered it in New York on 20 February 1920. Sadly, although he briefly championed the piece, he felt that it was too long. He did not really understand it and did not know how to interpret it. Since that time, it has not had the popularity that it deserves. Great advocates include Alicia de Larrocha and Garrick Ohlsson.

In my preparation of this review, I listened to the Fantasia with the score. One marvels at the technical difficulties of this music. It is mainly flamboyant, if a little brittle, and there are intimate moments. Falla seems to have realised a perfect balance between the “grand romantic style” and a sense of Andalusian improvisation.I was interested to read that music historian Ann Livermore has suggested that the Fantasy was a late tribute to Isaac Albeniz, who had died in 1909. Certainly, much of the pianism would suggest the elder composer.

The liner notes advocate that it is a lively journey through an “arid landscape” – and Falla’s newfound admiration of Stravinsky is becoming clear. Yet, here are “guitaristic influences, energetic dances, evocations of sultry evenings, traditional songs and resounding echoes of flamenco that are expressed in novel, authentically pianistic figurations”. Javier Laso captures it all in a stunning, expressive performance.

Béla Bartók’s last Piano Sonata was dedicated to his second wife, Ditta Pásztory-Bartók. The first of the three movements, Allegro moderato, lively and dissonant, is “martial in character”. The liner notes says that it was “probably inspired by the verbunkos, a traditional Hungarian recruiting dance”. The second, which is alleged to evoke the Hungarian Plains, is sustained and serious. The finale, Allegro molto, is a good old-fashioned rondo, refreshing and dynamic. It is interesting that Bartók has used classical forms for each movement. Modernity came by way of dissonance, percussive use of the piano, and lack of key signature. There is folk music influence, but this integrates these “overlooked resources” into “an international style weary of chromaticism”.

Spanish pianist Javier Laso studied piano at the Conservatorio Superior de Música de Salamanca, and received many awards. He furthered his education at the Franz Liszt Academy in Budapest. He recorded Schubert, Schumann and Bach. He was recently nominated for the German Schallplattenkritik award.

The concluding paragraph of the liner notes reveals the raison d’être of this disc. Javier Laso “travels through four apparently unrelated worlds, distilled from four lives dispersed by the tide of history. Each of those lives cultivated a new landscape in a new century, and yet all four were shaped during the same period of European history – the moment at which the old continent ceased to see itself as the centre of the known universe.”

There is no doubt that these four works represent four distinct strands of Western music. They are a salutary reminder that Classical music may be harder to pigeonhole than we would first imagine.

John France

Buying this recording via a link below generates revenue for MWI, which helps the site remain free