Edvard Grieg (1843-1907)

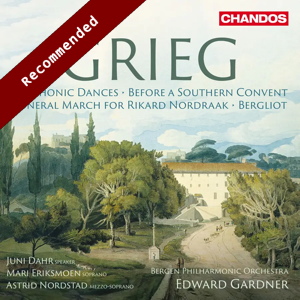

Symfoniske Danser (Symphonic Dances) Op. 64 (1896-1898)

Bergliot Op. 42 (1871 orch. 1885)

Foran sydens kloster (Before a Southern Cloister) Op. 20 (1870)

Sørgemarsi over Rikard Nordraak (Funeral March for Rikard Nordraak) EG 107 (1866, orch. 1907 by Johan Halvorsen)

Juni Dahr (speaker), Mari Eriksmoen (soprano), Astrid Nordstad (mezzo-soprano)

Women’s voices of the Bergen Philharmonic Choir, Edvard Grieg Kor

Bergen Philharmonic Orchestra/Edward Gardner

rec. 2021/2023, Grieghallen, Bergen, Norway

Norwegian texts and English translation included

Chandos CHSA5301 SACD [64]

Grieg’s Piano Concerto and some of his music for Peer Gynt are well known but I was not aware of his other orchestral music or even knew that he had written much, thinking of him as primarily a composer of chamber and piano music. So these orchestral works were completely unfamiliar to me and, I suspect, would be equally unknown to many readers, except those who have a particular enthusiasm for Grieg or for Norwegian music more generally.

The main work here is the Symphonic Dances. This is in four movements, each drawing on Norwegian songs from the collections made by Ludwig Mathias Lindeman (1812-1887), a composer and indefatigable collector of Norwegian folk music, which he published in a series of volumes. The melodies are all catchy tunes, nicely varied and contrasted and grouped into movements in either ternary or rondo form. Grieg wrote the work originally for piano duet, a version he liked to play with his friends. He then orchestrated them, and did so brilliantly, having gained experience as a concert pianist and conductor. He also liked to conduct the orchestral version. He thought highly of the work, which he saw as a unity. He refused to let the individual movements be published separately and called them Symphonic Dances. They are the nearest approach to a symphony which he made in his maturity – there was a youthful symphony which he withdrew. The work is not technically symphonic, since there is no movement in sonata form and it does not have the weight of a symphony, but it is attractive and enjoyable.

There follow two vocal works. Bergliot is described as a declamation with orchestra. The combination of spoken voice with orchestra, usually known as melodrama, is an unstable one, and, though several composers have tried it, it is not often successful. (The dungeon scene in Beethoven’s Fidelio and some passages in Stravinsky’s Oedipus Rex are among the few successful ones I can think of.) Bergliot presents a poem by Bjørnstjerne Bjørnson (1832-1910), who was the theatre manager in Oslo and also a friend of Grieg. Indeed they planned to work on an opera together but this never happened. The poem deals with a historical eposide in tenth century Norway. Bergliot, originally Bergljot Håkonsdatter, was the wife of a local aristocrat, Einar Thambarskelfir. In 1050 he led a rebellion against the tyrannical king Harald Hardrada. (Harald is best known in Britain for his unsuccessful attempt to take the English throne in 1066, in which he was killed by Harold at the battle of Stamford Bridge.) In the course of this, Einar and their son Eindride were assassinated om the orders of Harald. Historically, Bergliot raised an army and eventually made peace with Harald, but in the poem she renounces vengeance and prepares to live a solitary life.

Listening to this on a recording is like hearing a radio play with incidental music. The text is presented, and very well too, as far as I can judge, by Juni Dahr, speaking quite quickly, without histrionics but movingly nevertheless. The music is mostly in short, indeed tiny snippets, effective enough but mostly not amounting to more than a few seconds at a time. The two exceptions are the threnody on hearing of the deaths of the two men and the lament at the end. There is not enough music to turn into a suite so this is the only way to hear it.

This is followed by the cantata Foran sydens kloster, which translates as Before a Southern Convent and also uses a text by Bjørnson. This dramatizes anothet incident from the same period. Ingigerd was a daughter whose father was killed by one of his friends. She wanders through Europe and eventually arrives at a convent. The cantata presents a dialogue between her and a second voice, which must be one of the nuns. Eventually Ingigerd is allowed to enter and a chorus of nuns welcomes her. This is a more straightforward, indeed an effective and beautiful work, and it is not surprising to learn that Grieg was pleased with it and often performed it.

Finally, we have an early work, a funeral march Grieg wrote for Rikard Nordraak, a friend of his who died early from tuberculosis. It is a sombre work as befits its occasion. Grieg wrote it originally for piano but later arranged it for wind band with percussion. After Grieg’s death Johan Halvorsen made an orchestral version which was played at Grieg’s funeral and which is what we hear here.

These performances seem exemplary to me. I have already praised Juni Dahr’s narration in Bergliot. Mari Eriksmoen and Astrid Nordstad are the excellent soloists in Foran sydens kloster and the women of the two choirs involved make a good job of their short passage. The Bergen Philharmonic sound thoroughly at home with these works, as indeed they should be and Edward Gardner guides the proceedings with a sure hand. He has already made a well-received recording of the Grieg Piano Concerto with some of the Peer Gynt music (review). This is an appropriate successor and, I understand, is to be followed by more of Grieg’s orchestral music. The recording is a SACD but I was listening in two channel stereo, in which forn it sounded fine. The booklet is informative and texts and English translation are included. This is a fine production all round.

Stephen Barber

Buying this recording via a link below generates revenue for MWI, which helps the site remain free.