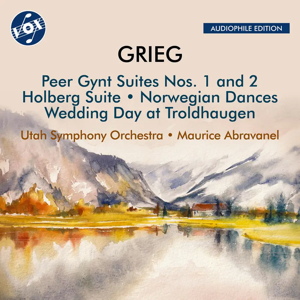

Edvard Grieg (1843–1907)

Peer Gynt, Suite No. 1, Op. 46 (1875)

Peer Gynt, Suite No. 2, Op. 55 (1875)

From Holberg’s Time, Op. 40 (1885)

Wedding Day at Troldhaugen, Op. 65, no. 6 (1896)

Norwegian Dances, Op. 35 (1881)

Utah Symphony Orchestra/Maurice Abravanel

rec. 1975, Salt Lake Tabernacle, Salt Lake City, USA

Audiophile Edition

Vox VOX-NX-3039CD [68]

Maurice Abravanel’s reputation has benefitted in recent years from record collectors who—after depleting the archives of every extant cough, snort, and sneeze ever issued by Furtwängler, Mengelberg, Klemperer, et al—have plumbed the depths of the archives ever further to satisfy their thirst for new musical thrills. Not that Abravanel is an obscurity. His LPs with the Utah Symphony, the ensemble he built over his three-decade stint in Salt Lake City, were reliable choices for budget-minded music lovers during the 1960s and 1970s.

An unfair preconception may have developed in some listeners’ minds that Abravanel’s music-making, too, is of bargain basement quality. Admittedly, upon listening to his cycles of the Tchaikovsky, Mahler, and Sibelius symphonies, for example, one at first may wonder why anybody would be interested in a conductor whose interpretive heat never climbed above room temperature. It would be wrong to dismiss his recordings, for they have their virtues, not least being the handsome playing of the Utah Symphony. More importantly, as this latest Naxos reissue from the Vox back catalog demonstrates, Abravanel excelled in those “minor” works now mostly long vanished, but that once upon a time were popular indispensables on concert programs.

Edvard Grieg’s Peer Gynt suites are among the archetypal examples of this amorphous genre. Once the delight of many, it is music that has been used and abused by a century of pop culture to the point that “Morning Mood” and “In the Hall of the Mountain King” have become eye-rolling clichés. They sound anything but in Abravanel’s hands. Warm, finely detailed, and eschewing extreme interpretive intervention, this 1975 recording restores the enchantment of this winsome music. “Solveig’s Song” makes an especially memorable impression: the Utah strings glide effortlessly on the wings of its melody, overlooking a nameless region between joy and tender sorrow that defies the reach of words.

No less enjoyable are Abravanel’s genial interpretations of From Holberg’s Time and the Norwegian Dances. Their easy-going boisterousness is art that disguises art, belying the concentrated effort of orchestra and conductor.

Understated, but never faceless, Abravanel’s conducting attractively frames the baritonal timbre of the Utah Symphony. Centered on oaken winds and plump, but not-too-succulent, brass, it makes one nostalgic for bygone times when orchestras sounded like orchestras, long before the faddish conceit of the ideal orchestra being a giant chamber ensemble had caught on. Vox’s production favors the middle and lower registers, imparting a rich, smooth bass that never turns boomy, with a touch of light glimmering at the high end. The informative original liner notes by Joseph Braunstein and Everett Helm have been retained.

Mahler alone among composers, Klaus Tennstedt once declared, required a conductor’s total devotion. With Grieg and his ilk, on the other hand, a conductor could basically grit their teeth, lie back, and go through the motions. As Abravanel elegantly rebuts on this release, however, it is not always the “immortal masterpieces”, but those smaller-scaled gems easy to take for granted—Sir Thomas Beecham’s beloved “lollipops”—that often need the most care to make them sing.

Néstor Castiglione

Buying this recording via a link below generates revenue for MWI, which helps the site remain free.