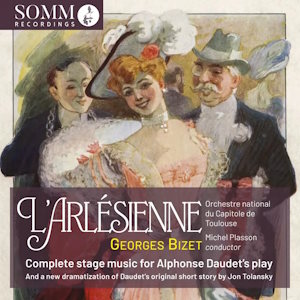

Georges Bizet (1838-1875)

L’Arlésienne, Op 23 (1872 version, including dramatised adaptation)

Jon Tolansky (speaker)

Orféon Donostiarra

Toulouse National Capitol Orchestra/Michel Plasson

rec. 1985, Halle-aux-Grains, Toulouse

SOMM Recordings SOMMCD0682 [73]

Before the nineteenth century composers who wrote incidental music for plays generally restricted themselves to overtures and dance movements between scenes, and the question of what do with the music when it was being performed in concerts away from the theatre generally did not arise. But after the time of Beethoven’s Egmont and Mendelssohn’s Midsummer Night’s Dream composers began to experiment with movements of melodrama, with frequently fragmentary passages of music co-existing with and illustrating spoken dialogue; and this caused problems when the concert promoters scheduled the pieces for non-dramatic performances. The brief snippets of scherzo material in the Mendelssohn score, for example, make no musical or dramatic sense when shorn of the verses they interrupt. Composers frequently addressed this problem by compiling suites of incidental music for concert presentation, often expanding the orchestration or combining sections of music into larger units – Grieg’s Peer Gynt proved a model for many examples by Sibelius. These suites also helped to keep music in circulation even after the plays for which they were originally written fell from the repertoire. Bizet was one such example, taking the fragmentary music written for a small pit-band for Daudet’s play L’Arlésienne and constructing a four-movement suite which achieved concert success even after the original play had vanished from the boards. After Bizet’s death his friend Ernest Guiraud constructed a second Arlésienne suite importing music from other sources and furnishing probably the best-known number of the score in his combination of the Farandole with the originally independent Prelude from Bizet’s theatre score (as distinct from the composer’s choral version). And for many years those two suites were all of Bizet’s L’Arlésienne that audiences ever heard, establishing themselves as one of Bizet’s most popular scores and garnering a whole heap of superb recordings.

It was only in the 1970s, as musical scholars began to investigate the scores of these bodies of theatrical music as originally written (Peer Gynt was another early candidate for such investigation), that conductors began to regularly perform the complete Bizet music (which had long been available in print but comprehensively neglected) or their own arrangements of the material. One of these pioneers was Michel Plasson, who produced a 1986 LP of the Bizet score in its version for small orchestra – both on physical and financial grounds, the theatre could only accommodate 26 players – and enabled us to hear much of the vocal music which had hitherto been almost totally unknown. Even so he made no attempt to furnish the dramatic context for which Bizet had originally composed his music. Indeed, it has only been in the last twenty years or so that record companies have attempted to supply this missing element in their recordings of incidental music, sometimes supplying new spoken material to illuminate the isolated passages of musical fragments even where the original dramas are beyond redemption or resuscitation – one thinks of Elgar’s Starlight Express.

And that is to a certain extent what has now been undertaken here. We are given first the Plasson recording of the complete score Bizet originally wrote for Daudet’s play. The drama itself may not have been totally beyond salvation – it was after all found suitable to provide a complete operatic libretto for Cilèa’s L’Arlesiana a few years later – but at the same time it is a ramshackle construction hampered by the fact that the titular heroine never actually makes an appearance on stage. As such it betrays its origins, which were not dramatic at all but a short story telling of obsession and confusion. When the music is played (as here) without the dialogue the results are not really very satisfactory. The chorus, which Bizet indicated should sing from behind the scenes, is here lent more prominence although its contributions and lyrics are not really essential; in the meantime, much of the remaining melodrama designed to accompany spoken voices sounds relatively feeble to anyone acquainted with the more substantial versions of the same music familiar from their inclusion in the suites. The music is played in an edition credited to Dominique Riffaud which is described as based on the original 1872 material; it differs in some minor respects from the version as published by Choudens, although the variations are generally minimal – apart from the truncation of the Carillon interlude familiar from Bizet’s own first suite, which is shorn of its final repeat given in full in the vocal score.

When Jon Tolansky enters on the final twenty-minute track to read his version of the original Daudet short story, however, his voice comes as rather a shock. In the first place it is recorded in a totally different acoustic to the musical contributions, resembling nothing more than an old-fashioned BBC studio with minimal reverberation and a close-to-the-microphone delivery which flattens out any sense of dramatic involvement. Secondly, after the performance of the overture as before, the music fades down as the voice begins, so that the sense of combination of the two media – dialogue and orchestral commentary – is totally sacrificed. Indeed, most of the melodrama material which was novel in the Plasson recording is eliminated in the heavily abridged version of the plot we are given here. And no attempt is made to let us hear any of the characters actually speaking their lines; instead Tolansky in his matter-of-fact way simply reports what we already know about the action. Bizet’s carefully designed interrelationship between words and music simply vanishes under these circumstances. The story itself is carefully pruned, and the suggestion of sentimentality that could so easily have surfaced is carefully circumvented; but there is nothing here that draws me back to either the story or the music.

Recordings of the suites from L’Arlésienne are of course legion, and I would hesitate to recommend any one in preference to any other although I still have a soft spot for Sir Thomas Beecham’s old 1950s version by which I first made the acquaintance of the music. That of course employs full orchestral forces; Plasson too seems in places to use a larger body of strings than in Bizet’s time, although this has its advantages in the more substantial numbers and he slims down the players to a single quartet in places during the background music of the melodramas. But there are a couple of alternative recordings of the complete incidental music which employ actors to speak Daudet’s lines over the music as the composer envisaged, going back to a vintage 1957 recording conducted by Albert Wolff available on both Accord and Naxos and (bizarrely) a more recent Capriccio disc with the dialogue in German. Christopher Hogwood produces his own edition of the score for chamber orchestra; but this is far from complete and omits the chorus, although it probably conforms most closely to the sound of Bizet’s original orchestration.

Plasson however remains the most clearly recommendable version on CD of Bizet’s incidental music in its original form. Indeed I would recommend it to anyone who loves the orchestral suites and would like to hear more of the original inspiration. And anyone who loves Bizet is surely accustomed by now to various forms of editorial entanglements. Somm’s publicity oddly describes the performance as “rare;” but the recording itself is still available on two different EMI downloads although neither have any coupling, and are therefore decidedly short measure at 51 minutes. This Tolansky “dramataied [sic, twice!] adaptation” of the short story does at least make some attempt to redress the dramatic balance, and this version appears to be the only currently listed as available on CD. An additional bonus comes in the shape of Tolansky’s own substantial booklet note, which appears to be considerably more informative than anything provided with previous issues of this recording.

It’s a pity, though, that Bizet’s short seven-bar coda for the final curtain is so utterly predictable.

Paul Corfield Godfrey

Buying this recording via a link below generates revenue for MWI, which helps the site remain free