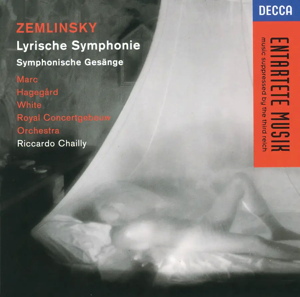

Alexander Zemlinsky (1871-1942)

Lyrische Symphonie, Op.18 (1923)

Symphonische Gesänge, Op.20 (1929)

Alessandra Marc (soprano), Håkan Hagegård (baritone), Willard White (bass-baritone), Royal Concertgebouw Orchestra / Riccardo Chailly

rec. 1993, Grotezaal, Concertgebouw, Amsterdam, The Netherlands

German texts & English translations included

Presto CD

Decca 443 569-2 [65]

In the late 1980s, Riccardo Chailly made for Decca a series of discs of music by Zemlinsky, including the early Symphony in B-flat and the fine Die Seejungfrau. I bought two of those discs but his subsequent recording of the Lyrische Symphonie eluded me, possibly because I already had Lorin Maazel’s 1981 DG recording in my collection. (I believe the Maazel version was subsequently licensed to Brilliant Classics – see review.) I’m very pleased, though, that Presto Classical have licensed this Chailly disc, originally released in 1994, for their catalogue of on-demand CDs. The disc was first issued as part of Decca’s important ‘Entartete Musik’ series. Subsequently, it was reissued in 2003, coupled with more Chailly recordings of Zemlinsky and Rob Barnett reviewed that release.

Lyrische Symphonie is a setting of poems (in German translation) from the 1913 collection of poems entitled The Gardener by the Bengali poet, Rabindranath Tagore (1861-1941). The work, which plays continuously, consists of seven poems set alternately for baritone and soprano soloists; they are accompanied by a substantial orchestra. In his exemplary booklet essay, Andrew Huth points out that it was Zemlinsky himself who drew a parallel between the Lyrische Symphonie and Mahler’s Das Lied von der Erde. However, Huth goes on to make an important distinction between the two works. “Mahler’s great song-symphony is above all a recollection of experience, with meticulous and lingering attention to the beauty and transience of the natural world. In Tagore’s verses there is yearning, but no nostalgia. Emotion is internalised rather than projected into the world of nature, which is here felt only as a shadowy nocturnal background to the poet’s dream-like experiences of love.” I’d take slight issue with that argument; it seems to me that, in addition, the emotions are far more ardently and directly expressed in the Tagore poems which Zemlinsky selected. Nonetheless, I think Huth is right to draw the distinction which he does between Mahler’s masterpiece and Lyrische Symphonie.

I’d not heard this performance before receiving the disc but I was impressed. Chailly has two fine soloists. As a matter of subjective taste, I prefer the contributions of Håkan Hagegård. That’s chiefly because though Alessandra Marc offers much ravishing tone, her vibrato often clouds the words. There are no such issues with Hagegård, whose voice is firm and clear; and he’s no less expressive than his soprano colleague. Hagegård is splendidly ardent in the often-volatile music of the first song and he has the requisite power for the hothouse sentiments of the fifth song. Arguably, he reserves his finest singing for the last movement which has, as Andrew Huth says, “the character of an epilogue”. The music takes its cue from the opening lines: ‘Friede, mein Herz, / laß die Zeit für das Scheiden süß sein.’ (Peace, my heart, / let the time for parting be sweet.’) Zemlinsky’s music is achingly beautiful and Hagegård rises to the occasion.

Though I have a reservation about her diction, I like Alessandra Marc’s performance in all other respects. In the second song she articulates with gorgeous tone the longing of a young girl for an unattainable prince. Even more impressive is her delivery of the fourth song. Zemlinsky’s vocal line is quite angular but Ms Marc makes it a thing of beauty – which is what the composer surely intended. Her final involvement is in the sixth song. Here, Zemlinsky pushes the boundaries of tonality to an extent that would surely have gained approval from his brother-in-law and sometime pupil, Schoenberg. The music is adventurous but Alessandra Marc’s delivery of the vocal line – and the feelings of despair in Tagore’s poem – is gorgeously done.

Riccardo Chailly conducts the work with great conviction. He’s helped by superb playing by the Royal Concertgebouw Orchestra, whose Chief Conductor he was at the time (1988 – 2004). The very opening of the work, potently projected, makes the listener sit up and pay attention. I also admired the playing during the busy passages of the third song, while the way the orchestra delivers the soft, subtle scoring of the fourth song leaves us in no doubt that this movement is the still centre of the work. The RCO also makes a distinguished contribution to the final song; the playing is very beautiful. At the end, when words can no longer express the emotions of the epilogue, the orchestra provides a wonderful postlude. Arguably, the resonance of what I presume was the empty Grotezaal in the Concertgebouw robs us of a degree of clarity in some of the more complex passages of scoring. On the other hand, the richness of the orchestral sound offers ample compensation.

This is a fine account of Lyrische Symphonie; I’m glad that thanks to Presto Classical I’ve been able to hear it and belatedly add it to my collection.

It’s the companion piece, the Symphonische Gesänge which really justified this disc’s inclusion in the ‘Entartete Musik’ series. Two things about this work would have enraged the Nazis when they achieved power in Germany not long after Zemlinsky had composed the score. One was his Jewish heritage, of course. But in the eyes of the Nazis, he compounded that offence by choosing to set poems by African-Americans. The seven poems which Zemlinsky selected cane from an anthology of poems by poets of the ‘Harlem Renaissance’. The collection was published in a German translation in 1929 under the title Afrika singt. Zemlinsky seems to have lost little time in setting seven of then – four by Langston Hughes (1901-1967) – to music.

The musical language of Symphonische Gesänge is a long way from the late ultra-romantic language of Lyrische Symphonie. As Andrew Huth points out, in Zemlinsky’s few compositions between the two works he had moved towards a leaner style; I find it hard to envisage the poetry of Langston Hughes and his colleagues lending itself to the sort of luscious musical idiom that worked for Tagore’s verses.

Symphonische Gesänge is a much tougher proposition than the Lyrische Symphonie. For one thing, the orchestral scoring is lean and fairly uncompromising.Much of the selected poetry is dark, even bitter; the final poem concerns the aftermath of a lynching in Georgia and there’s a grotesque irony both in the title ‘Arabesque’ and in the bitterly perky music to which Zemlinsky set the words of Frank Horne (1899-1974). Earlier in the set comes ‘Bad Man’, a setting of lines by Langston Hughes. Zemlinsky’s music is very punchy – appropriately so – and his setting is as sharply pointed as the words. In truth, most of the words and the music in Symphonische Gesänge deal in bitter emotions; there’s no room for lightness or levity here. The closest Zemlinsky comes to repose is in ‘A Brown Girl Dead’ by Countee Cullen (1903-1940). This is a sad song and Zemlinsky’s setting is all the more effective for its relative restraint; the emotions are dignified, both in terms of Cullen’s words and the way in which Zemlinsky clothes them in music.

Willard White is a very fine soloist and he’s backed up by acutely pointed orchestral accompaniments under Chailly’s direction.

Decca’s recordings are good. The sound for Symphonische Gesänge is quite close and tight, giving an immediacy which is very suitable for the music. As I said earlier, I have a mild reservation about the resonant acoustic when it comes to clarity in Lyrische Symphonie. However, this is a small point and should not deter any purchasers; in any case, tonal opulence, which the engineers have certainly produced, is very appropriate for this work. Andrew Huth’s notes guide the listener expertly through works that may be unfamiliar.

This is a very valuable disc of sharply contrasting scores by Zemlinsky and I’m delighted that it’s once again available, thanks to Presto Classical

Help us financially by purchasing from