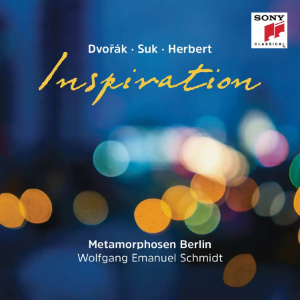

Inspiration

Josef Suk (1874-1935)

Serenade for Strings, Op. 6 [1892]

Love Song, Op. 7 [1898?, arr. Schmidt]

Victor Herbert (1859-1924)

Three Pieces for Cello and Strings [1900]

Antonin Dvořák (1841-1904)

Serenade for Strings, Op. 22 [1875]

Metamorphosen Berlin/Wolfgang Emanuel Schmidt (cello)

rec. 2013/15, Telefex Studio Berlin

Sony Classical 88875 130202 [71]

According to the booklet, Metamorphosen Berlin “was founded in 2010 by Indira Koch and Wolfgang Emanuel Schmidt”; this presumably accounts for the former’s receiving billing as “concertmaster,” though this program includes little prominent solo violin work.

The Dvořák Serenade, recorded in 2013, packs a wallop – not the first term you’d associate with it. The approach is flowing and straightforward, but rather intense, particularly in the outer movements. The first movement’s syncopated accompaniments push forward, with barely any transitional ritard before the brisker “B” section. The Finale, similarly, is taut; the opening tempo is bracing, with the contrasting episodes pushing faster. It’s brilliantly done, but a bit of a hard sell.

The other movements offer lovely insights along the way. The waltz is gracious, with an adept rubato marking off the main section, and surprisingly big, resonant forte cadences; the repeat of the “B” section is introspectively inflected. The Scherzo scurries without actually rushing, although the bassi can be unsubtle with the motif. There was room for more delicacy and restraint in the straightforward Larghetto, although at no point is it objectively “too loud.” In this context, the very short pauses – that between the last two movements excepted – seem an artistic choice rather than a careless production.

A few years later, everyone’s settled in a bit, and their unified Suk is less insistent, less determined to prove something. In the luminous first movement, Schmidt’s cantabile shaping enhances the brief pivots through the minor. The second movement has a waltzlike lift, with an unexpectedly turbulent lead-back from the “B” section; the sustained, reflective Adagio moves patiently through the melodic quavers. Just to show the players havcen’t lost their energy, the finale is brisk and incisive, with a lovely, saturated tone in the big homophonic chorale. The playing is beautiful, the commitment and musicianship undeniable. It seems almost churlish to suggest that, even putting native Czech practitioners aside, the normally stolid Münchinger (Decca Eloquence) captures more of the score’s Bohemian charm and nostalgia.

Collectors and completists may want the shorter works, but I’m not sure they add up to that much. In Schmidt’s arrangement of Suk’s piano piece Píseň lásky (Love Song), the bass pedal point seems uncharacteristic, but the conductor himself fills out the solo cello part with firm, ample tone, over supporting textures more soloistic than orchestral. Victor Herbert’s own arragements of three of his own piano pieces – an affirmative, thoughtful opener; an uplifting piece that becomes a cakewalk; the last, lyrical but unsettled – are pleasing but slight.

Given the intensity levels, the vivid, immediate sound might be too much of a good thing. The depth is impressive, but the peaks harden slightly, so watch your levels.

Stephen Francis Vasta

stevedisque.wordpress.com/blog

Help us financially by purchasing from