Sir Charles Villiers Stanford (1852-1924)

Shamus O’Brien (1895)

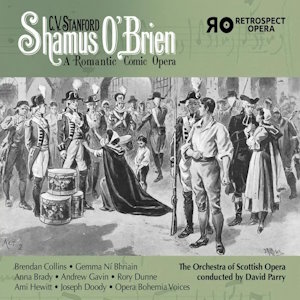

Brendan Collins (baritone) – Shamus O’Brien

Gemma Ní Bhriain (mezzo-soprano) – Nora O’Brien

Andrew Gavin (tenor) – Mike Murphy

Rory Dunne (bass-baritone) – Father O’Flynn

Ami Hewitt (soprano) – Kitty

Joseph Doody (tenor) – Captain Trevor

Catriona Clark (soprano) – The Banshee

David Parry – Sergeant Cox

Opera Bohemia Voices/The Orchestra of Scottish Opera/David Parry

rec. 2023, Silver Cloud Studios, Glasgow; Champs Hill, UK

Libretto included

Retrospect Opera RO011 [2 Cds: 137]

This release has already been excellently reviewed by my colleague John Quinn so it would be foolish to go over the same ground, as he has laid out the historical and musical situation so admirably.

I am still reeling from reviewing Somm’s recent collection of Stanford’s Irish songs which were so inconsequential, so inane and so dull – with a few exceptions – that it was a real trial listening to them. Given that Shamus O’Brien is an unashamedly ‘Irish’ opera, my critical expectations were set to zero. However, the romantic comic opera’s overture was recorded back in 1916 when Stanford went into the Columbia studios to record four sides of his music, and it gave some idea of the work’s vivacity. The question has always been whether the overture, which does promise rich lustre and heralds a stirring brassy theme, sets up expectations that could not be realised.

Act 1 opens with a song from one of the main characters, Father O’Flynn (of course), accompanied by a jog-trotting chorus of some tunefulness. We are introduced to the characters with rapidity, but there are sign that Stanford’s orchestral imagination is operating at a level beyond the merely commonplace – there’s an evocatively winding clarinet, for example, in the ‘Sortie’ though the main ethos remains that of the intended nature of the work, Opéra comique, as one can plainly hear in ‘Well, he’d take me by the hand’ a duet for two of the characters who, blinded by a coup de foudre, flirt and fall in love. There are the expected chest-swelling martial declarations of defiance in defence of Old Erin from the central character, Shamus, in ‘I’ve sharpened the sword’ though it’s soon followed by an indefensibly tedious scene full of predictable ensembles and orchestration, which dissipates any tension.

The final two scenes of the Act are rather revealing of Stanford’s dilemma. Baleful brass figures as Nora, Shamus’ wife, reflects on the Banshee, suggests a darker opera working in parallel that could have moved closer to Dvořák but the long finale – over 13 minutes – is a terrible let-down after this, with the introduction of the Uilleann pipes, an offstage Banshee, and utterly undistinguished other than for Shamus’ ‘Darlint adieu’ which Brendan Collins sings with appropriate elegance.

The villain is Mike Murphy, sung with oily self-justification by Andrew Gavin, though opportunities for self-pity in Act II (‘Ochone, when I used to be young’) could have developed characterisation – opportunities that Stanford could not pursue, even had he wanted to, so hemmed in was he by the nature of the genre. Stanford is on autopilot during much of the middle of the second act but the tone does darken as the work hastens to its rather precipitate end. This unevenness of tone at the most dramatically intense moments of both Acts is more than a nod to theatrical convention and does suggest – at least suggests to me – that whilst Stanford was happy enough to bow to the dictates of a rollicking comic piece, he could not quite suppress his natural sense of drama.

The singers are all of a fine standard. Anna Brady speaks the dialogue for mezzo Gemma Ní Bhriain, the only such occasion of someone filling in – much in the way old opera sets used to work – but Brady is a first-class speaker and one doesn’t notice the ‘join’. Ní Bhriain sings the role of Shamus’ wife, Nora, excellently. Joseph Doody is the British Captain Trevor and I have to agree with John Quinn. He sings finely but he has clearly been encouraged to speak his dialogue as a twit and sounds uncomfortable doing so, as well he might. The other lamentable and ever-present element is George H Jessop’s libretto which is of the ‘You couldn’t blame us/We must see Shamus’ variety (that is a direct quotation but there are dozens like it). The risible rhymes fall as lightly on the expectant ear as a ten-ton weight.

In this opera Stanford was looking back to mid-century precedent – Alfred Cellier is the most obvious, though there are French operettas on which he drew as well. He didn’t have recourse to G & S patter songs though Stanford could here be situated in Sullivan’s wake, I suppose. So does the overture, recorded back in 1916 by Stanford, set up unrealistic expectations? I’m afraid so. There’s no law, written or unwritten, that says that comic opera should not include moments of heightened drama the better to convey an ultimately happy resolution – indeed it’s a feature of some comic operas. Whilst there are a number of diverting elements here and whilst the opera is considerably better than I feared, it fails because one feels Stanford is most engaged by the dramatic potential of the action (which he is least able to develop) and is least engaged by the frivolous workings out of the plot, such as it is.

That’s to take nothing away from the performers, or from conductor David Parry who moonlights as the character of Sergeant Cox, a spoken role. The booklet documentation is compendious and excellent, giving a wealth of information about the work, its historical context and comes complete with libretto. Shamus O’Brien was Stanford’s most popular opera, but what about The Critic, of which he also recorded the Masque in that 1916 session? I wonder if there’s mileage in that?

Jonathan Woolf

Previous review: John Quinn (March 2023)

Help us financially by purchasing from