Arvo Pärt (b. 1935)

De Profundis (1980/2008)

Dmitri Shostakovich (1906–1975)

Symphony No. 13, Op. 113 “Babiy Yar” (1962)

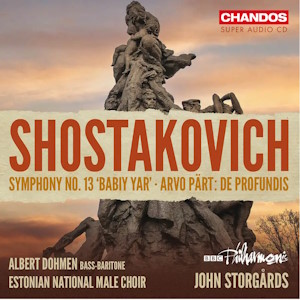

Albert Dohmen (bass-baritone)

Estonian National Male Choir

BBC Philharmonic/John Storgårds

rec. 2023, MediaCityUK, Salford, UK

Chandos CHSA5335 SACD [70]

Dmitri Shostakovich’s Symphony No. 13 has been unlucky on records since the splendid recordings conducted by Kirill Karabits (Pentatone, PTC5186618) and Riccardo Muti (CSO Resound, CSOOR9011901), both released in 2020. As its condemnations of racism and authoritarian manipulation of truth, along with celebration of humor’s endless capacity to subvert both have increased in relevance, singers capable of suitably conveying the work’s power appear to have decreased. Matthias Goerne’s 2023 recording is perhaps the symphony’s discographical nadir; his voice sounding hopelessly overwhelmed by the music, with the habitually lackadaisical Andris Nelsons doing little to help. This recording, sung by Albert Dohmen, is better, but not by much. Simply put: music and voice are fundamentally mismatched.

Composed at the height of Shostakovich’s neo-Mussorgskian phase, the Symphony No. 13 requires the soloist to assume the role of secular evangelist declaiming the Truth to his audience, as if Pimen from Boris Godunov had been reimagined for the Atomic Age. It was that activist quality in Yevgeny Yevtushenko’s verses that immediately captivated Shostakovich, but provoked bemusement and hostility from others. Although ideological disputes with Soviet officialdom about the opening movement, “Babi Yar”, were certainly the main cause of the symphony’s troubled reception at home, the detestation the composer’s friends and colleagues felt towards poems whose noble intentions they felt could not compensate for their artlessness unto gracelessness was also sincere. Puzzled non-Russian speakers may gain better understanding from Ian MacDonald, who memorably described Yevtushenko’s “ramshackle apocalyptic irony being very much like that of a Soviet Bob Dylan”, then recall the controversy that erupted among belletrists when the author of “Blowin’ in the Wind” was awarded the Nobel Prize for Literature in 2016.

Suavity and elegance are the foremost attributes of Dohmen’s interpretation—acceptable for Hugo Wolf or Gustav Mahler, perhaps, but entirely missing the point of this denunciative work. His all-too smooth delivery in “In the Store” of “Zyabnu, dolgo v kassu stoya” (“I am shivering, waiting in line at the cashier for a long while”), for example, sounds as if he were observing the doings at the local Aldi, rather than the miserable, shortage-plagued Soviet stores that Yevtushenko had in mind. “Humor” is improbably lacking in its namesake trait, with the flat-footed Dohmen tending more towards hoariness than hilarity. He is at his best in the final movement, “A Career”, where its more inward character—and faint hints of Shostakovich’s late style to come in the coda—seems better fitted to his voice. Less endearing is his affectation of beginning certain sustained open syllables without vibrato, then switching course mid-way.

Storgårds and the BBC Philharmonic, as elsewhere in this mini-cycle of Shostakovich’s later symphonies, are very fine, often excellent, supported as always by the rich Chandos production. Brass and winds aptly characterize the galumphing mobs in the quickstep that follows the opening section of “Babi Yar”, with plodding tuba imparting menace and rube brutality. Strings shimmer ominously in their conjuration of the claustrophobic paranoia of “In the Store” and “Fears”, with maliciously chattering muted trumpets cutting through the latter. The Estonian National Male Choir, no strangers to this work, sing superbly.

Preceding the Shostakovich is Arvo Pärt’s De Profundis from 1980, programmed here in its 2008 arrangement for male chorus and chamber orchestra. Although David Fanning in his liner notes unconvincingly attempts to make a case for its relevance to the Shostakovich, Pärt’s idiom and especially its Christian mysticism make it an incongruous discmate. Had Storgårds opted for the comparatively swifter tempi of Karabits’ recording, it would have been possible to program in place of the Pärt another, more appropriate work composed in the same year by a fellow Estonian: Boris Parsadanian’s Symphony No. 7. A one-movement symphonic eulogy to Aram Khachaturian scored for slightly larger forces than the Shostakovich (plus organ, minus vocal soloist), with an evocative male choral part that seems to call forth from the beyond, it is one of the exemplars of late Soviet symphonism. That something like Pärt’s De Profundis was chosen instead is consistent with this album’s inconsistencies.

Néstor Castiglione

Help us financially by purchasing from