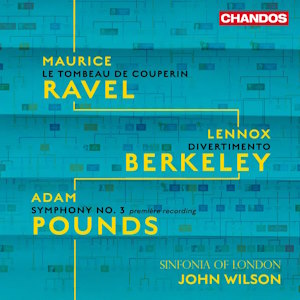

Maurice Ravel (1875-1937)

Le Tombeau de Couperin (1914-1919)

Lennox Berkeley (1903-1989)

Divertimento in B flat major, Op.18 (1943)

Adam Pounds (b. 1954)

Symphony No.3 (2021)

Sinfonia of London/John Wilson

rec. 2022, Church of St Augustine, Kilburn, London

Chandos CHSA5324 SACD [66]

The reason to get this disc is for the recording of Maurice Ravel’s Le Tombeau de Couperin; a finely-etched, balletic interpretation that is virtually a digital recreation of Jean Martinon’s treasurable reading with the London Philharmonic set down back in the twilight of shellac (currently available as part of the Decca Conductors’ Gallery box set, Eloquence 4842117). Laurence Davies in his 1970 overview of the composer’s orchestral music was ambivalent about this transcription’s virtues over the piano original. Had he heard this dapper interpretation by John Wilson and the Sinfonia of London, he may have come around to embracing it unreservedly, so persuasive and immaculately Ravelian it is. Their “Prélude” is swift, but never harried. Woodwinds soar in delicate play of interlacing textures, never once disclosing to the listener the formidable challenges in breath control this movement poses. For once its gently nostalgic evocation of the clavecin is preserved in its orchestral guise; its wistful longing for le Roi Soleil-era innocence, viewed from the trenches of the Great War, made all the more moving for it. Ravelian, too, is Wilson’s light-footed “Forlane”; here a nimble fluttering of irony and pathos, a cryptic smile traced on a mask. Oboist Tom Blomfield’s sweetly plangent playing embroiders the “Menuet”; and after the shadows cast by its G-minor musette are dispelled, his instrument’s touching refrain of the movement’s theme wipes away the face paint, revealing that the music’s sentiment is sincere after all, its tears genuine. The “Rigaudon” that closes the suite is vernal, bouncy; not the over-loud bumbling one typically hears. Phrasing is impeccably detailed, instrumental layers deftly terraced, and all of it sings as if with the naturalness of breathing. Wilson’s interpretation reminds one why every new recording conducted by him feels like a little Christmas to collectors.

Less convincing is this album’s loose theme around Nadia Boulanger and her school of corporate neoclassicism, which tended to confuse surface with substance, resulting in an internationalist school that subordinated the spontaneous to Fordian principles of mass-production.

Interestingly, as Mervyn Cooke’s fine liner notes explain, Lennox Berkeley solicited private lessons from Ravel, who apparently admired the “sensuous side” of the Englishman’s music, but rejected him as a student because of his lack of “technical finesse”. By the time of Berkeley’s 1943 Divertimento, which follows the Ravel on this album, he had more than made up for this perceived deficiency, but one wonders whether something more valuable was lost in the process. Efficient, sturdy, and pleasant, it also could have been cranked out by any one of the Boulangerist gatekeepers of music that once ruled both sides of the Atlantic. Whatever “fun” may exist in this misleadingly titled work is of the sort made by timid school children whose activities are sempiternally monitored by a domineering headmaster.

Adam Pounds’ Symphony No. 3, which concludes this program, follows the Berkeley with such stylistic immutability that one can hardly believe it was composed nearly 80 years later. Not surprising, therefore, that Pounds was Berkeley’s pupil, although hearing chronic Boulangerism this deep into the 21st century is about as incongruous as seeing a Berliet Dauphine cutting through traffic in the age of Teslas and Rivians. A polished and well-ordered illustration of “play” and “emotion”, Pounds’ symphony, which is dedicated to Wilson, was fashioned as a response to the COVID-19 lockdowns of 2020–2021. There is no explicit program, but neither is there anything distinctive about the music itself; an impression augmented by its reliance on postmodern pastiche, whose clever mimicry sounds like makeshift placeholders for gaps that should have been filled with intrinsically interesting and original music. Bruckner is specifically invoked in the slow movement, but the finale almost sounds like it could have been a discarded draft for the opening of Rachmaninoff’s Symphonic Dances. On my fourth listening of the symphony, I was trying to pinpoint what the Shostakovichian scherzo reminded me of. Then it hit me: the “Waltz” from Boris Tchaikovsky’s Sinfonietta for strings.

Immediately, I took the disc out and played the Tchaikovsky instead.

Néstor Castiglione

Previous reviews: John France (February 2024) ~ Paul RW Jackson (March 2024)

Help us financially by purchasing from