Déjà Review: this review was first published in April 2003 and the recording is still available.

Felix Mendelssohn (1809-1847)

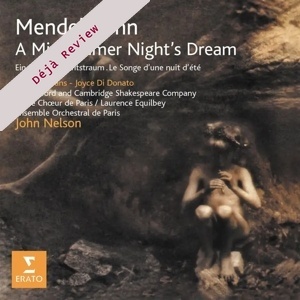

A Midsummer Night’s Dream: Overture (1826) and Incidental Music (1843)

Ruy Blas Overture (1839)

Rebecca Evans (soprano)

Joyce di Donato (mezzo-soprano)

The Oxford and Cambridge Theatre Company

Le Jeune Choeur de Paris

Ensemble Orchestral de Paris/John Nelson

rec. 2001, Orchestre National d’Ile de France, Alfortville, France

Originally reviewed as a Virgin Classics release

Erato 5455322 [77]

Mendelssohn followed the trend of many of his contemporaries – Liszt and Berlioz, for instance – by responding to the creative possibilities offered by literary and pictorial sources. The Overture was therefore an important type of composition for him, gaining an independence away from the context of preceding an opera or other stage work.

While this interest in the concert overture is certainly the general trend in Mendelssohn’s approach, the Overture to Victor Hugo’s drama Ruy Blas has definite links with the theatre, even if it has subsequently achieved an independent status in the concert hall. So too, of course, the link with Shakespeare’s Midsummer Night’s Dream, though in that case the incidental music for the theatre followed the original concert overture by a distance of 17 years. Not that the listener would discern this from the music.

Of all composers Mendelssohn was surely the greatest prodigy as a teenager, this overture and the Octet the supreme examples of his youthful genius. However, it is wrong to dwell on the fact that this music was written by so young a composer, since that deflects us towards astonishment at his precocity, when we should be concentrating on the extraordinary nature of the music itself.

The translation of Shakespeare was one of the most significant literary developments in Germany during the first half of the 19th century, capturing the imaginations of writers, artists and composers alike. The Overture and Incidental Music to A Midsummer Night’s Dream are the quintessential example of Mendelssohn’s ‘fairy music’, and therefore the score poses particular challenges to the performers even today, in terms of dexterity and intonation and style.

John Nelson and his Parisian forces respond with enthusiasm and consummate skill. The conductor has centred much of his career in France and is a noted Berlioz interpreter. He also knows his musicians and directs them with rare sympathy. The sparkling performance of the Overture reflects all this, helped as it is by a clear and atmospheric recording. Tempi and articulation are beautifully judged.

These features are carried over into the succeeding Scherzo (another tour-de-force of ‘fairy music’, and into the other items which follow. Some are substantial movements, whereas others are shorter and serve in close tandem with scenes from the play. It is here that the special nature of this recording comes in, since extracts of the play are used in combination with the music. The vocal projections are clear in enunciation, and the pacing of music and drama is well directed and therefore effective. If there is a criticism to be made, it is in the organisation of the cue points and spacings relative to these things; sometimes the words begin immediately upon the music, making it hard for the technically inclined listener to programme his CD player to his preference.

Mendelssohn was commissioned to write the music for Ruy Blas in 1839, in connection with a Leipzig production of the play. This typical Hugo tragedy, with passionate emotions and irreconcilable conflicts, was ‘cordially disliked’ by the composer; but that did not prevent him from creating one of his most stirring and effective orchestral works, whose stature is apparent from the initial sonorous chorale statement, setting the tone for the whole. This dramatic rendition completes this most appealing new issue, a splendid addition to the catalogue.

Terry Barfoot

Help us financially by purchasing from