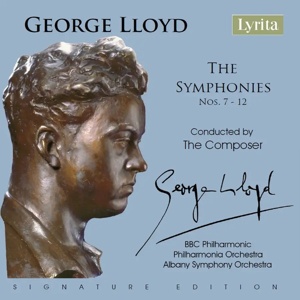

George Lloyd (1913-1998)

Symphony No.7 ‘Proserpine’ (1957-59)

Symphony No.8 (1961 orch 1965)

Symphony No.9 (1969)

Symphony No.10 ‘November Journeys’ (1981-82)

Symphony No.11 (1985)

Symphony No.12 (1989)

Orchestral Suite No.1 from The Serf (1938 arr 1997)

BBC Philharmonic Orchestra, BBC Philharmonic Brass, Philharmonia Orchestra, Albany Symphony Orchestra/George Lloyd

rec. 1984-2000, New Broadcasting House, Manchester, Watford Town Hall, London; Troy Savings Bank Music Hall, Troy, UK

Lyrita SRCD 2418 [4 CDs: 292]

As I wrote in my review of the first volume of these reissues, Lyrita and the George Lloyd Society have reached an agreement by which Lyrita has taken over the sale and hire of all the scores held by the Lloyd Society as well as recordings conducted by Lloyd in the 1990s. This ‘signature edition’ will initially arrive in two big boxes that contain his entire symphonic canon, all twelve symphonies, and this is the second of the two boxes, symphonies seven to twelve with the Orchestral Suite No.1 from his opera The Serf also included.

The final six symphonies occupied Lloyd from 1957-59 to 1989, a three-decade period during which he still found new things to say and found structures malleable enough to craft works of character, colour and depth. Symphony No.7 was only premiered in 1979, though it had been composed twenty years earlier, in a performance preserved by Lyrita itself on REAM.1135 (review) where Edward Downes conducts the BBC Northern Symphony Orchestra, which later became the BBC Philharmonic, the orchestra that plays it for Lloyd in 1986. The continuity therefore is strong and the differences between the two performances, at least in timing terms, minimal to non-existent. For the symphony Lloyd drew on large orchestral forces and in the opening movement of the three-movement work unleashed a rich tapestry of terpsichorean writing buttressed by percussive vitality and small cell-like military calls. He subtitled the symphony ‘Proserpine’ taken from Greek mythology, and it’s the central Lento that draws from Lloyd his most serene writing, which in its absorption of the solemn also brings with it melancholy elements too: possibly he was reflecting his experiences in the War. The grand wind tracery here and the eloquent horn writing become part of one of his memorable pulsing tunes – so distinctively Lloydian – in a movement that is also as richly Straussian as it is operatic – it’s a kind of extended operatic intermezzo in places. For the Agitato finale Lloyd is terse with stirring thematic material, ratcheting the tension through cumulative drive punctuated by insouciant paragraphs – an ingenious mechanism to redouble the vehemence and then to wind down slowly.

Symphony No.8 was composed in 1961 and orchestrated four years later and it too takes a three-movement form, again with a central Lento. Once again Edward Downes, with the Philharmonia this time, recorded this commercially for Lyrita. He’s a touch faster in the opening movement but otherwise, once again, there are no structural dissimilarities between the conceptions, unsurprisingly as Lloyd conducts the same orchestra. Lyricism and the dance saturate the first movement – Lloyd was well-known as an operatic composer earlier in his career but it’s clear to me that he would have flourished as a ballet composer – and there is a considerable amount of colour and contrast, full of sectional dynamism and characterful colour. Listen to the percussion writing as well, which Lloyd inevitably handled with panache, and to a memorable tune that emerges after some symphonic strife. The Funeral march in the central movement emerges wraith-like though once again Lloyd’s gift for melodic efflorescence irradiates this movement. The thistledown finale is rather Mendelssohnian in inspiration, as Lloyd admitted to Lewis Foreman in the notes for the Downes recording, quoted by Paul Conway in his majestic booklet notes.

The Ninth dates from 1969. It’s a cheery retrenchment from the previous two symphonies with typically uplifting melodies, rich coloration and sonority – and also a lot more compact – but even here the central movement shows terse and even glowering evidence that not all is well, and that Lloyd was incapable of writing predictable music. The use of the solo flute in this central movement is distinctive. The finale’s frantic would-be triumphalism has an echo of Shostakovich about it – those fanfare figures and exuberance create a heightened mood of uncertainty; what precisely is being celebrated? One can take it seriously or one can accept the hijinks but were we able still to reference bipolarism, that’s precisely how I’d characterise this work.

Symphony No.10 is subtitled ‘November Journeys’ and is written for brass, here played by the BBC Philharmonic Brass in this May 1988 recording. The work has most recently been taken up by Abbey Brass under Tony Hindley, a very personable reading which I reviewed here, and by the London Collegiate Brass under James Stobart, who made the first recording, shortly before this Lloyd-directed one. Stobart also made a fine job of it. It’s the Lloyd symphony that has drawn most conductors to it, principally because of its specialist brass nature, which sites it securely in the British tradition. Listening to it again, I was struck by the mobile nobility of the Calma second movement and by Lloyd’s deft direction.

I’ve never been especially convinced by Symphony No.11 though others think very highly of it. It dates from 1985, lasts 59 minutes, and is cast in five movements. Certainly, it’s colourful and draws from Lloyd his habitually vivid use of sectional colour both in the fiery and the lyrical episodes. The Lento generates powerful intensity but one finds – well, I find – it lacks a true sense of motivation and there’s something – uniquely for Lloyd – oddly Iberian about the succeeding scherzo. The Grave fourth movement is strongly threnodic but sounds too Holstian in places and whilst those echoes of Mars pass quite quickly – and may, again, reflect echoes of his catastrophic wartime experiences – they sound to me insufficiently embedded in the fabric of the music. To balance the big opening movement we have a similarly big finale. Here Lloyd shows his compositional mastery in his use of motto themes, sonority and colour once again, control of metres, and use of insouciantly whistling tunes – all with the age of anxiety passages – that gradually coalesce in a most satisfying conclusion. To me, though, it is one of his more unfocused symphonies, notwithstanding its richness.

The one-movement No.12 subdivides into three – an Introduction and Variations, followed by an Adagio and Allegro finale. It was written in 1989. The Introduction is unusually gentle, with a liquid clarinet line and gauzy strings supporting. The variations are ingeniously varied, some of which are strongly rooted in popular song – or so it seems to me. The colour and intimate expression continues into the slow section before Lloyd unleashes a quiet start to the finale which gathers – through incremental use of percussion, as well as frolicsome, lighter winds – in richness. Characteristic Lloydian melodic distinction leads to a glorious, exultant bell-flacked peroration, after which the music muses quietly to the end. Whatever structures he uses, Lloyd always gave primacy to vivid themes, to maximum contrasts, and to his full powers of orchestration, prominent among which was his handling of percussion. Some composers are shy of it but not Lloyd.

The other work in the set is the Orchestral Suite from The Serf, written in 1938 but arranged decades later in 1997, the year before his death. Both it and the 12th are played by the Albany Symphony, who also play No.11. There are seven ‘scenes’ and reveal his indebtedness to, and love of, Italian operatic models. His writing here is richly upholstered and direct, with a beautiful love duet that is not, however, untainted by unease, a lithe panel where jagged rhythms alternate with his trademark insouciance. Elsewhere we find a full complement of his gift for characterisation. In the absence of a recording of the opera, the suite serves to suggest what we might be missing.

I realise I’ve already saluted Paul Conway’s notes but it deserves to be done again. As before, an inevitable loss is the LP sleeve art and I regret not being able to see D. G. Rossetti’s Proserpine which adorns the Conifer LP of No.7 so beautifully, the lonely Munch on the cover of Symphonies 9 and 2, and the 1814 view of Albany by James Eights on the cover of No.11. Still, Time rolls on and bears all its sons and daughters away. Note that the photographic booklet – Lloyd in pictures – is in the earlier box.

If you missed Lloyd’s symphonies or if you bought some piecemeal as they were released and have given away your LPs or if you’ve since caught up with some CDs but not nearly all the symphonic canon, here is your chance. You will be well rewarded. Lloyd’s music is direct even when elusive, commanding even when equivocal, and is strongly lyrical – some of his lyricism is simply unforgettable. It is also richly, ripely and colourfully orchestrated.

Here it is in two competitively priced boxes.

Jonathan Woolf

Help us financially by purchasing from