Frédéric Chopin (1810-1849)

Études, Op.10 and Op.25

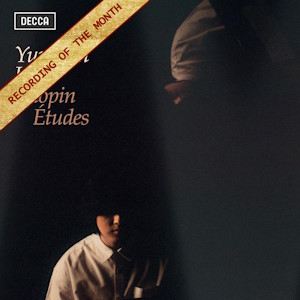

Yunchan Lim (piano)

rec. 2023, Henry Wood Hall, London

Decca 487 0122 [58]

Walter Pater once wrote that all art aspires to the condition of music; for Yunchan Lim the opposite may be true. For this pianist, Chopin’s Études find their inspiration in Shakespeare, Rilke and Greek Myth – and if not there in fountains of colour or dance, spiritualism, philosophy and science. They begin from the moment of Creation itself to absorb the emotions of desolation, loneliness, pain and desperation – they are a narrative of both the Universe and the Human. Lim’s Chopin is, unsurprisingly, not in the least static – rather it follows an infinite range, and this is sometimes difficult to square with the music – or Chopin – itself. But they are, it should be said, endlessly creative and imaginative performances that have required a little more thinking about than most recordings of the Études I have come across. This might be as much an interpretation of Yunchan Lim’s Chopin as it is a review of his recording.

If all great musicians have one thing in common it is their mutability; their interpretations are organic rather than the opposite. Originally, I was to have reviewed this disc in parallel with Lim’s recital of the Études at Wigmore Hall but the cancellation of his European Tour because of a hand injury made that impossible. I wondered, however, whether I might even recognise the two performances; this pianist’s proclivity for interpretative change (already there in his Rachmaninoff) is all but acknowledged at the end of the interview in the booklet note: “These imaginings have helped my interpretations, but they change every day. I’m sure that tomorrow I’ll have other ideas!”

I think mutability is more often a reflection of an artist’s search for perfection, an often unattainable one. Both Vladimir Ashkenazy and Maurizio Pollini whose greatest versions of the Études were done in 1959/60 and 1960 [on Melodiya and Testament, respectively] never bettered them in later recordings. The early Pollini recording is perhaps a slightly more interesting one historically having been made after the pianist won the Chopin Competition in 1960 but which he withheld from publication. This coincided with a decade where Pollini reconsidered his identity with the music he played and partly avoided Chopin entirely. (Pollini radically changed his view of the Études, too, since the EMI sessions remained unpublished for 50-years even though subsequent recordings were issued.) Yunchan Lim has by no means done this with Rachmaninoff – but it is perhaps revealing his first studio recording should not be of that composer.

Yunchan Lim’s Chopin is neither better – nor for that matter worse – than either the early Ashkenazy or Pollini. Nor is it particularly similar to either. But it is historically informed. The most interesting pianist he mentions in the interview in the booklet is the Russian Youri Egorov. Egorov died aged 33 in April 1988. There are at least five recordings of him playing the Chopin Études in existence, although most are of the Op.10 set; the only complete one can be found in the Et’cetera box set which was released in 2015. Egorov – like Alfred Cortot, another of the pianists that Lim cites – brought breathtaking poetic beauty to Chopin. He was, however, better caught live and any one of the Op.10 from Egorov’s recital from Nohant in 1982 or from the Op.25 from Pasadena in 1980 are crystalline jewels played with the most originally phrased beauty of tone. His technique sometimes lacks the precision of Lim’s but this hardly matters (as this also does in both the Cortot sets from 1933 and 1942). What perhaps makes Egorov’s Chopin so special is a sense of freedom and spontaneity that coexists with great tenderness and romance. But the exile he had to endure to attain what we hear in his playing also makes his performances of the Études both darker and more unsettling. Egorov’s interpretations are powered by very private intuitions – and that is something that is deeply ingrained within Yunchan Lim’s recording as well.

If Egorov and Cortot have rubbed off on Lim, and Vladimir Horowitz lurks somewhere too, like a ghost at the banquet, these are incidental influences, however – the Chopin we get on these recordings is very much of Lim’s making. One reason I am not particularly reminded of either the early Pollini or the Ashkenazy – or for that matter Stanislav Bunin’s recording on EMI – is because these all have a very direct musicality (and with Bunin – winner of the Chopin Competition in 1985 – a greater sensitivity in the lines he creates). Neither of the early recordings by Ashkenazy/Pollini are notably large-scale in their approach –although Pollini would become so in the 1970s, and Ashkenazy in his later Decca recording, too.

The Études, of course, begin with their technical challenges before the interpretative ones and these are as evenly spread through the Op.10 as they are through the Op.25. Nos. 1 of both sets are notable for arpeggios; Nos. 4, 9 and 10 of the Op.25 for chords and octaves. The Op.10 Nos. 3, 6 and 9 and the Op.25 No. 7 are the most lyrical of the sets requiring the most legato playing. But the greatest of pianists mask the difficulties with invention: in the Op.10 No.1 the leggiero voices and fluid stretch should perhaps be a reflection of what it has become known as, ‘Waterfall’; the Op.25 No.12 should make you forget entirely about the reams of arpeggios as it unravels into tragedy.

I did, as it happens, find some lack of balance in Lim’s Op.10 No.1 – it rather seemed to swell and dip in dual-tones, almost as if he had taken his description of this étude’s “cold expanse” to a near-literal degree. Vastness might be slightly misapplied, too, given the briskness he takes it at. However, on a second listening there is rather more depth to his playing, and not just in the formidable bass of the left-hand. There is a suppleness to the leggiero lines, although I think the resonant acoustic of Henry Wood Hall (or close balance of microphones) – or perhaps a combination of both – makes this sound a more apocalyptic reading than many. The water flows here with ferocious power rather than any kind of liquid-like fluidity, even given Lim’s meticulously played arpeggios – it’s a rather antithetical performance to the one by Egorov in 1982 which is as sublime as one gets in this piece.

But if there is a straightforward kind of thinking to the Op.10 No.1 that is not the case in the Op.25 No.5, for example. Lim’s ‘Wrong Note’ Étude is remarkable for its tenderness and expressiveness; the legato is often achieved by a perfect balance of pedalling and keyboard playing. The soul of the work is rendered through cantabile playing of the highest order. What exercised my mind during Lim’s playing of this Étude was his linking of it to the German poet Rainer Maria Rilke. A poet who sometimes embraced Nietzschean thought, new language and philosophy into an anti-Christian sentiment, Rilke held to a belief that poetry could reconcile beauty and suffering into art. The summit of Mahler’s ‘Resurrection’ Symphony seems Rilke’s destiny. Listen to this Étude as played here and one might think that Rilke and Lim are interchangeable.

Somewhere between these two – which might represent the creation and ascension in Yunchan Lim’s universe of Chopin’s Études – comes the rest of the pieces. There are, however, some simpler things that catch the breath – or perhaps require much less thinking in these. The Op.10 No.3 might not be one of these, however. Lim says it’s about “longing” – which resonates with its nickname ‘Tristesse’ – but I found this performance opens with harrowing, gaunt and almost severe phrasing. It begins in grief before reaching any sense of desire or yearning. There is certainly no lack of delicacy in the legato, nor a lustre in the tone; cantabile, if anything, is broadly understated. It’s gripping because the rubato is so flexible; and from this the emotional drama flows with perceptive meaning. Egorov, in his earliest recording of this piece from 11 November 1976, done in the studio in the Hilversum in the Netherlands, is certainly more conventional; Bunin more searingly tragic (and considerably more expansive with it).

The Op.10 No.12, the ‘Revolutionary’, was written by Chopin during the failed November Uprising of 1831. The Cadet Revolution was an armed rebellion between partitioned Poland and Tsar Nicholas I’s Russia eventually leading to Poland’s integration into the Russian Empire. Yunchan Lim finds his inspiration for this Étude more than two-thousand years earlier in Helen of Argos, whose abduction by Paris of Troy was the immediate cause of the Trojan War in the 12th Century BCE.

Lim was born to play the tempestuous key of C minor, in which this Étude is written. The ‘Revolutionary’ is brawny, but it is also passionate (appassionato). Some of the writing is con forza; the tempo Allegro con fuoco. Rather than the power mostly coming from the left hand it does so from the right one. Where you might normally expect more agility at the top end of the keyboard the reverse is often the case. What is perhaps unsettling about this piece is that it has no definite conclusion with no victory in sight. Lim’s performance is superb, gravitating to a more early twentieth-century performance such as that by Ignaz Friedman (whose recording is titanic) rather than Cortot or Egorov. The right-hand octaves are particularly explosive, the general tenor of the playing seismic in its flow. The stretto playing in the left-hand is like gunshot, but when bass is needed sounds like cannon fire. It is a performance that presses forward, often taking risks that pay off.

It’s probably the high point of the Op.10 set, but you get equally blistering playing in the No.2 and the No.4 Études where the attention to detail is phenomenally precise. There are different perspectives in the No.5 and No.10 of eastern and western colour.

The Op.25 Études are considerably more private works and quite possibly find this pianist in more comfortable territory – albeit more difficult one. As dazzling as he is as a pianist live in recitals, I have not found him to always be a particularly engaging one. If his performances tell us anything it is largely of half-written chapters, or of closed ones that he wishes to keep to himself. He can be a solitary young man, although when the inwardness slips open the revelations are often remarkable. These last twelve Études follow a similar journey; there is both discovery and restraint.

As with the Op.10 No.1 the first of the Op.25 ‘Aeolian Harp’ is arpeggio dominant. Another pianist I enjoy equally as much as Lim in this Étude is another South Korean – Julius-Jeongwon Kim (whose recording is on Stomp Music). Both not only achieve a miraculous intricacy, they also manage to conjure up a world of spectral and lightweight tone that succeeds in making the technique seem entirely superfluous to the poetry surrounding the music. (Lim also gives us a piano of magical delicacy in the opening bar.)

Op.25 No.4 presents one particular challenge and that is Chopin’s metronome marking of the quarter note being 160. Lim is one of the few pianists who comes close to this, although Vladimir Ashkenazy in his 1959/60 recording (the No.4 was recorded in 1960) is sensational: it’s a vortex of virtuosity and fluidity. If the technique with Ashkenazy is flawless it is partly because his smaller hand size gives him the agility to do this. Technically Lim is superb managing staccato passages with sharpness and precision. Are there hints of feverish desperation here, of hanging on by the coattails to something that is about to be lost? Perhaps. Pollini (1960) is almost resolved to resignation, Bunin in a performance of crippling slowness to something else entirely.

Staying with the magnificent Ashkenazy set, when it comes to the Op.25 No.6 it is again the flawless dexterity that allows this pianist to project a rather different view of the Étude. Rather than Yunchan Lim’s “gust” of wind that blows through this piece, albeit with superbly drilled trills written in thirds, Ashkenazy gives us a storm of them that has a Russian winter frost. Again, it is the Ignaz Friedman recording from the mid 1920s that hovers around the Lim performance – although Lim is more attuned to Chopin’s sotto voce voice, Friedman more inclined to produce a fuller sound.

Lim sees the Op.25 No.7 (nicknamed ‘The Cello’) as the “heart” of all the Études – and also the one that he found the most challenging and that gave him both the “greatest hardship and happiness”. It is by some margin the longest of the Études, with most pianists taking around 5’30 – except Cortot who takes 4’47 (1933) and 4’30 (1942). Vladimir Ashkenazy’s 1959 recording is a devastating performance: unlike a single photograph, this is like a series or album of them, colour, chromatic or sepia, faded or new. Balance and tone are almost microscopically detailed, the volume at pianissimo shaped like the floating of a bow across a cello’s string.

Yunchan Lim, I think, takes a different view of the No.7. The closing bars are remarkable – they don’t just dissolve, they vanish into a kind of misty invisibility. But to get to this point Lim is more uneven in his interpretation of dynamics. If the crescendo and decrescendo at the beginning are in balance the left-hand volume is often less in balance with the right-hand melody. Lim’s narration of this Étude makes this work only because these shifting dynamics are like piercing arrows. This cello is darker because it sings of pain.

The Op.12 No.12 kind of takes us full circle, and certainly does to the Op.10 set in that, as with the No.12 of that one, ‘The Revolutionary’, it is in the heroic key of C minor. Unlike the Op.10 No.1 ‘Waterfall’ this one is ‘The Ocean’ – its tsunami of arpeggios razing everything before it. Although I largely prefer a quicker tempo in this Étude (Stanislav Bunin is just on the slower side but is enormously powerful – the left-hand chords simply huge) Lim’s trajectory is on a far bigger scale than Vladimir Ashkenazy (curiously understated) and as impressively sweeping in its torrential swell, sharp accents and muscular pulse. It seems to end with the tragic collapse of everything that began in the opening bars of the Op.10. No.1.

So, what to make of Yunchan Lim’s new recording of the Études? If we begin with some of the language he uses to describe each of them a theme emerges. Words, or some derivative of them, are repeated throughout his interview in the booklet: Loneliness occurs three times, pain three times, desolate twice. Then there is: fear, rage, solitude, tears and regret. When Lim speaks of loneliness it is specifically about men: Chopin himself, Rilke (Op.25 No.5) and the old man overcoming his regrets and pain by recalling his young lover who fades away to nothingness in Op.25 No.7. The Études begin for Lim at Creation and end in song at the end of the world. They take in nature, literature and human emotions on an epic scale. These are in no sense whatsoever your usual recording of these piano pieces because the pianist has pretty much told us what each one means to him which invariably is never the case with other recordings. How far that relates to each Étude is down to how each listener responds to Lim’s performance of it – and in some cases he is vague enough to leave us asking questions we could probably never answer (such as in Op.10 No.9 where he refers simply to Shakespeare’s The Tempest – well, I could write a book on Prospero alone).

If we strip out all the background behind this recording it leaves it on a more equal footing with some of the other ones I have compared it with. I have largely found Lim’s playing to be on a slightly more Romantic scale – and if the freshness and brilliance of sound is very much his own, there is also a nod towards some of the great Chopin players of the past. Ignaz Friedman only left five recordings of the Études from 1925/6 (two from Op.25, three from Op.10) and they play for just under nine-minutes but almost certainly the Op.10 No.12 cannot failed to have made an impression upon him, as the Op.10 No.7 did on Vladimir Horowitz. Likewise, the poetic beauty and long lines you hear in Youri Egorov are equally there in Yunchan Lim’s recording. There are risks – the tempo for the Op.25 No.4 is unusual, but pays off. The more profound Études (Op.25 Nos. 5 and 7) are magnificent, complex in their intellectual thinking, and deeply personal in their meaning.

The recorded sound for this disc is very fine. It took me some weeks to be able to listen to this disc through my preferred medium (headphones) but the Henry Wood Hall acoustic is less of a problem than I had originally thought – Études such as the Op.10 No.2, where the finger work is of such crystalline precision, now make this perfectly clear. (Any of the Études with arpeggios, trills or scales sound phenomenally detailed on this recording.)

Yunchan Lim’s Chopin Études is a disc I will return to – not least because I think I have more to discover in it. It is a journey through these works, and something of a shared experience; an insight into a pianist’s thinking at the time they were recorded, even if we know it is a mutable one. If it does not displace the great Ashkenazy set made when he was 22, Lim’s can happily sit beside it.

Marc Bridle

Help us financially by purchasing from