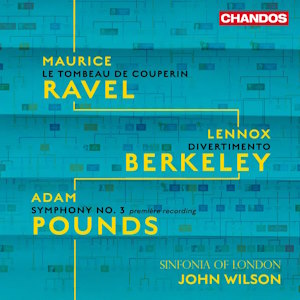

Maurice Ravel (1875-1937)

Le Tombeau de Couperin (1914-1919)

Lennox Berkeley (1903-1989)

Divertimento in B flat major, Op.18 (1943)

Adam Pounds (b. 1954)

Symphony No.3 (2021)

Sinfonia of London/John Wilson

rec. 2022, Church of St Augustine, Kilburn, London

Chandos CHSA5324 SACD [66]

Maurice Ravel declined to teach the young Francophile Lennox Berkeley, suggesting instead that he study with the great pedagogue Nadia Boulanger, which he did. Berkeley did take the young Adam Pounds as a private pupil in the late 70s, so there is a tenuous link among the three composers here, stretching over a century. Berkeley learned a great deal from studying Ravel’s scores and the elegance and clarity we find there we also find in Berkeley’s music. Likewise, there is great clarity in the writing of Adam Pounds, a composer new to me, alongside impeccable orchestration.

Ravel’s Le Tombeau de Couperin is an arrangement of four movements from the six-movement piano suite of the same name written in 1917. Each movement is named after a Baroque dance form, and each is dedicated to the memory of a friend killed in WW1. The piano suite is technically demanding and so, too, is the orchestral version which in its demands is like a small concerto for orchestra. The woodwind all have virtuoso solos throughout and the work is not one that could be attempted by amateurs. No amateurs are present here and all rise to the immense challenges of the piece.

I thought Mr Wilson’s tempi were on the fast side but checking with score and metronome found them to be spot on Ravel’s markings and that most other conductors are on the slow side. My go-to recording for many years has been Jean Martinon and the Orchestre de Paris, released in many versions on EMI. His opening movement is almost thirty seconds slower than here. These brisk tempi must have kept the players on their toes and the whole work sounds fresh and exciting.

Berkeley’s Divertimento was premiered in 1943, though there is no hint of wartime angst in the work. It is, as is all of Berkeley’s work, elegant and refined, and each movement is perfectly balanced in form and content. The sweetness of the melodies is tempered by some naughty dissonances that add a piquancy to the musical mix. The sound-world of French composers such as Poulenc, Sauget and of course Ravel is conjured up in the works four movements. Berkeley is, however, his own man, and the scherzo third movement could not have been written by anyone else. Once again, there is much virtuoso solo writing, again handled beautifully. The many in-movement tempo changes are smoothly and elegantly managed by the conductor. This and his Serenade for Strings (1939) are among my favourite Berkeley works and it is great to have another recording of this neglected gem.

BBC Radio 3 recently broadcast a performance of Howard Skempton’s piano concerto which they described as ‘daringly melodic’. I think there is something sad when writing melody is seen as ‘daring’. Adam Pound’s music is indeed very melodic, tuneful even, and following the BBC’s thinking he must be very daring. His Symphony No. 3 was completed in 2021 at the height of the Covid pandemic. The composer says that the work aims to reflect the “sadness, humour, determination and defiance” which was felt by the populace during that dark time.

The piece is in a very approachable mid-twentieth century style and covers a wide range of emotions. The first movement follows on naturally from the Berkeley work and is permeated by a sense of unease. The second movement is a sardonic waltz very much reminiscent of Shostakovich’s ventures into the genre. It is not joyous but very much a dance of death, conjuring up images of whirling spectres or lost dreams. The following Elegy ‘Homage to Anton Bruckner’ is beautifully constructed and touching in feeling. There is some wonderfully sonorous writing for the brass, which evokes the sound world of the master. The driving finale is once again reminiscent of Shostakovich, here in heroic mood joined at times by John Williams. There is something cinematic about the whole work and that is no bad thing. There was a time that comparing symphonic music to film music was seen as pejorative, but film music communicates instantly with its audience and so, too, does Mr Pounds. We need music like this today, music that communicates and is not hidden within magic squares and arcane formula. We also need music like this in the concert hall, so let us hope Mr Wilson is able to programme the work some time in the future. It is thrilling on disc and would be doubly so live. The symphony is dedicated to these performers, and I am sure the composer could not have wished for better champions.

The liner notes by Mervyn Cooke are detailed, very readable and appear in English, French and German. The recorded sound is up to Chandos’ usual, improbably high standards.

Paul RW Jackson

Previous review: John France (February 2024)

Help us financially by purchasing from