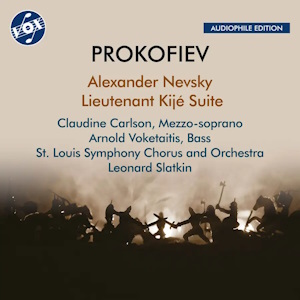

Sergei Prokofiev (1891-1953)

Alexander Nevsky (Cantata), Op 78 (1938/9)

Lieutenant Kijé Suite, Op 60 (1933/4)

Claudine Carlson (mezzo-soprano), Arnold Voketaitis (bass)

St. Louis Symphony Orchestra and Chorus/Leonard Slatkin

rec. 1977/79, Powell Hall, St. Louis, USA

Texts, translations included

VOX VOX-NX-3033CD [59]

For those who may not be aware, Prokofiev extracted a cantata from his film score for Sergei Eisenstein’s Alexander Nevsky and a suite from his score for Alexander Feinzimmer’s film Lieutenant Kije, thus accounting for the two works we have on this CD. The performance of the Alexander Nevsky cantata here was originally released in LP format in 1977 on Candide, which was, along with Turnabout, a Vox label. It then was reissued in 1981 with this Lt. Kije Suite and Ivan the Terrible on a three-LP set on Vox entitled Prokofiev – Music from the Films. All three works were next released on a double-CD set in 1990 on Vox, this time labeled as Prokofiev – The Film Music. I obtained all three of these incarnations when they came out. This new reissue contains the best sound of all of them, undoubtedly because of the excellent remastering of Andrew Walton and tape transfers of Mike Clements. The original recordings were of superior quality to begin with, being the work of Marc Aubort and Joanna Nickrenz, who were well known for their fine recording productions. (Note: there was a 2005 Mobile Fidelity SACD of this Nevsky and Kije that I’ve never heard.)

I reviewed Thierry Fischer’s recording of the Alexander Nevsky cantata and Lt. Kije Suite back in January, 2020 here and did not mention Slatkin’s go at these works when I made comparisons with the competition because it was unavailable at the time. Now it enters the field in this brilliant remastering and certainly warrants inclusion among the very finest Nevskys on record.

The opening movement, Russia Under the Mongolian Yoke, brims with ominous atmosphere as it exudes both a sense of oppression and anger. The chorus sing the ensuing Song about Alexander Nevsky beautifully in the outer sections, while the interior portion has plenty of spirit and energy. Here and throughout the work one notices that Slatkin’s tempos are consistently well chosen and other aspects of phasing always seem to capture the mood and emotional tenor of the music. The Crusaders in Pskov is one of the finest renderings of this movement on record: the low brass snarl and percussion roar while the chorus emit their repetitive chant, “Peregrinus expectavi pedes meos in cymbalis est”, that grows from a quiet, robotic utterance to a profoundly imperious torment.

The brief Arise, Ye Russian People is sung with zest and confidence, while the orchestra infuses much vigor into Prokofiev’s iridescent scoring. The Battle on the Ice, the centerpiece of the work, begins with the appropriate dark atmosphere from quivering and slithering strings and then develops into a juggernaut of orchestral and choral forces charging ahead for battle. I think I can say this account of the whole movement is unsurpassed by any other recorded performance I know of. Claudine Carlson delivers a heartfelt account of the Field of the Dead with her dark and lovely mezzo voice. Alexander’s Entry into Pskov brims with triumph and joy as the gong and bells roar and the chorus sing with a celestial fervor, especially in the ending. My only quibble is that I wish the chorus had been miked a little more closely, because in loud passages the orchestra, in vivid detail, often dominates the sound field.

The Lt. Kije Suite also gets a splendid performance: I could run through each of its five movements and find little to criticize. Again, the sound is very detailed and powerful, especially for its late-1970s vintage. But there is one aspect to this performance that might limit its appeal: Romance (No. 2) and Troika (No. 4) are presented in their vocal versions. Arnold Voketaitis sings well in both, though his voice is quite overwhelming in parts of Romance and thus may be miked a little too closely. Still, Romance comes off quite well, but Troika, despite Voketaitis’ fine singing, is missing the verve and color of the orchestral rendition. Let’s face it, this music is so well known in its orchestral version that many listeners won’t accept another way of hearing it. For one thing, a very popular Christmastime instrumental version of it is commonly played here in the US and North America, and probably in many countries across the globe. Anyway, Slatkin’s interpretation, especially in his tempo choices and sensitive shaping of the score, is just fine throughout the work and he draws excellent performances from the orchestra.

The album notes by the late Richard Freed are quite informative, though I must take issue with a comment he makes about Prokofiev’s orchestration (see below*). As for the competition on record in these two works, there is a plethora of it. In fact, there are many recordings to choose from with these couplings. Abbado/LSO on DG has both as well as the Scythian Suite. He’s very good in all works, though I would give the edge to Slatkin in Nevsky. Previn/LA Philharmonic on Telarc, is quite convincing in both Nevsky and Kije, though again I would favor Slatkin in Nevsky: Previn’s 1986 sound reproduction is impressive but the performances of the The Crusaders in Pskov and Battle on the Ice are a bit less grim and not quite as vital. The aforementioned Thierry Fischer/Utah SO on Reference Recordings Fresh is also quite good, though comparatively tame alongside Slatkin. Reiner/CSO on RCA is also quite good but has somewhat dated sound, and again Slatkin has the edge in Nevsky.

Verdict: if the vocal version of Lt. Kije is acceptable to you, then Slatkin could be placed at the top of the heap in these works. Only Abbado might be a better acquisition for potential buyers, because he includes the Scythian Suite. Despite that advantage, I’ll still go with Slatkin.

Robert Cummings

Help us financially by purchasing from

Note

*In a footnote Richard Freed writes that “Prokofiev did not orchestrate his music for the Eisenstein films himself.” (The referenced films are Alexander Nevsky and Ivan the Terrible.) Freed goes on to identify Pavel Alexandrovich Lamm as the orchestrator, whom he says also did the orchestration for other Prokofiev works including the operas Betrothal in a Monastery and War and Peace. I’ve read elsewhere of these claims that Prokofiev had ghost orchestrators, so let me set the record straight. Prokofiev, who was a master orchestrator, as demonstrated by early works like the Scythian Suite, was also very prolific. It is pretty well known, or so I thought, that in the latter part of his career he developed a unique method of orchestration by reducing it to a sort of “short-hand” form, and then having a paid assistant convert it to “long-hand”, to conventional orchestration, that is. That way, the busy Prokofiev could quickly move on to his next project.

To cite just one authoritative source, in the book Sergei Prokofiev – Materials, Articles, Interviews – compiled by Vladimir Blok (Progress Publishers, 1978), Russian composer and musicologist Dmitry Rogal-Levitsky relates an encounter with Prokofiev regarding the manuscript of War and Peace: “He [Prokofiev] handed me several sheets of music paper covered in music written in his firm hand. The manuscript was an extremely detailed score written on several lines, as many as ten or more in places. Everywhere there were notes indicating which instruments should play which passages.” When Rogal-Levitsky said it was complicated, Prokofiev replied, “Not at all! All that has to be done now is to write the parts out on separate sheets of music and everything will be ready. I usually indicate the minutest details in a score like this, and Pavel Alexandrovich [Lamm] simply follows my indications.”