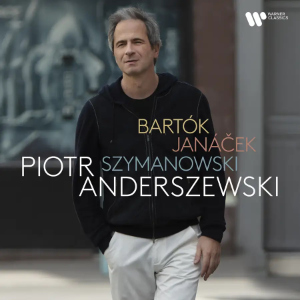

Leoš Janáček (1854-1928)

On an Overgrown Path, JW 8/17 – Book 2 (1908-1912)

Karol Szymanowski (1882-1937)

Mazurkas, Op. 50 – Nos. 3, 4, 5, 7, 8, 10 (1924-1925)

Béla Bartók (1881-1945)

14 Bagatelles, Op. 6, Sz. 38 (1908)

Piotr Anderszewski (piano)

rec. 2016, Polish Radio, Warsaw, Poland (Janáček); 2023, Teldex Studio, Berlin, Germany (Bartók, Szymanowski)

Warner Classics 5419789127 [63]

Piotr Anderszewski committed Karol Szymanowski’s major works to disc twenty years ago: he recorded Masques, Métopes and Third Piano Sonata for Erato. He has waited until now to add to his Szymanowski discography. This interesting programme also contains apposite pieces by Bartók and Janáček. I only wish he would have included more of the Polish composer’s Mazurkas, because there is room on the disc. Anderszewski plays this music to the manner born, and is equally convincing in Bartók’s Bagatelles, but I have a few issues with his Janáček.

Janáček composed ten character pieces with the overall title On an Overgrown Path in 1901-1908, each with a descriptive title. He then decided to add five pieces without such titles. He completed the first two to his satisfaction, while the others were left in sketches. Few pianists perform Book 2, so it is good then to have it: it is every bit as fine as the first set. One can concentrate on them without being influenced by the more familiar Book 1.

The pieces were composed in the period of Jenůfa, of Janáček’s early maturity, before he developed his later, trenchant style. On an Overgrown Path may be described as quasi-impressionistic, unlike his spikier later works. The pianist should not overdo the dynamics, especially on the higher end of the scale. This is the one place I feel Anderszewski falls a bit short. He follows the score, so whenever Janáček indicates ff, Anderszewski really hits the keys with vehemence. I find this less appealing than the more idiomatic interpretations of Czech advocates. The authoritative Rudolf Firkušný studied with the composer (recordings on DG or RCA). Jan Bartoš included only the first two pieces of Book 2 (on Supraphon – review). Anderszewski reorders these pieces: the longest and most imposing is placed last rather than fourth. That convinces by creating a decisive conclusion to his cycle.

Anderszewski’s Szymanowski and Bartók, on the other hand, are superb in every respect. I can readily take his bolder approach. The Mazurkas come from the later part the Szymanowski’s career, when he became influenced by the folk music of the Tatra Mountains. The greater dissonance of these works may also be traced to his interest in the music of Stravinsky. Some of the Mazurkas sound rather primitive, even barbaric, with drone effects. They are constructed with the unmistakable folk rhythms of the mazurka in triple time, even if this is not always apparent at the outset of a piece. The pianist has also chosen his own sequence here, Nos. 3, 7, 8, 10, 5 and 4. He begins quietly with No. 3 with its repeated notes, but without a mazurka rhythm until after the first thirty seconds. He concludes his series with what for me is the most approachable of the selections here, No. 4, less dissonant and more tonal than some of the others. Its emphatic chords contrasting with quiet passages are most effective. It concludes on sonorous octave notes in the tonic key. Chopin was undoubtedly influential here, but Szymanowski composed the Mazurkas with his own original voice. It is a pity Anderszewski did not include more of them here.

Anderszewski gives us the full set of Bartók’s Bagatelles, though. For me, they are the high point of this disc. Most of these pieces are very brief (the longest No. 12 takes around four minutes), but there is a great deal of variety. Bartókcomposed them before Bluebeard’s Castle, but they already display the modernist streak that he was to develop later in his piano works. As has been pointed out elsewhere, the first Bagatelle even has each hand in a separate key, four sharps vs. four flats. The piece begins with single notes played simply and slowly. The second Bagatelle is fast, with repeated notes, before becoming more elaborate. The music can be mysterious and haunting, as in the third Bagatelle, or big and powerful in the next one, marked Grave. That fourth one reminded me of Debussy’s La Cathédrale engloutie.

The pieces tend to be contrasted, as when No. 5 Vivo is followed by Lento of the sixth Bagatelle. Many of them are extremely short. For example, Nos. 2 and 4 each under a minute long. Even so, they present a real challenge to the pianist in their virtuoso requirements. Anderszewski meets it handily.

Bartók arranged for orchestra the last Bagatelle Valse: Ma mie qui danse – Presto. It is the second movement of Two Portraits; he borrowed the first from his earlier Violin Concerto. I find the original piano version of this Bagatelle more convincing than the orchestral one.

The Bagatelles suit Anderszewski’s exceptional technique and detail-oriented approach to a tee. The recorded sound, bright and transparent. also compliments these pieces, as it does Szymanowski’s Mazurkas. The Bartók makes this disc well worth having, as does the rather small selection of Mazurkas. I would seek out other recordings of the Janáček for the complete series of On the Overgrown Path by a pianist better attuned to the composer’s style. The main shortcoming of this disc is Anderszewski’s very brief note in the booklet that tells us in three languages nothing worthwhile about the music and nothing about himself.

Leslie Wright

Help us financially by purchasing from