Déjà Review: this review was first published in March 2002 and the recordings are still available.

Nikolai Myaskovsky (1881-1950)

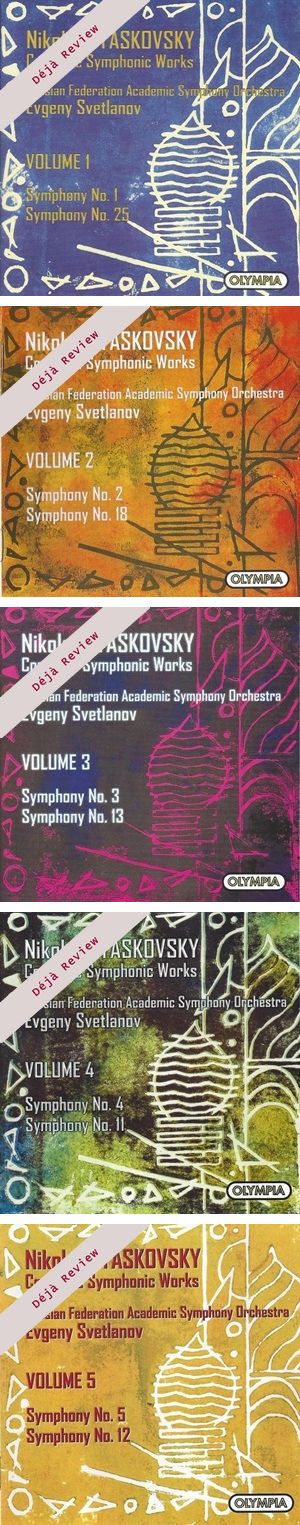

The Complete Symphonic Works, Volumes 1-5

Volume 1

Symphony No 1 in C minor, Op 3 (1908 rev 1921)

Symphony No 25 in D-flat major, Op 69 (1946 rev 1949)

Russian Federation Academic Symphony Orchestra/Evgeny Svetlanov

rec. 1991-3, Great Hall of the Moscow Conservatory, Russia. DDD

Olympia OCD 731 [78]

Volume 2

Symphony No 2 in C-sharp minor, Op 11 (1911)

Symphony No 18 in C major, Op 42 (1937)

Russian Federation Academic Symphony Orchestra/Evgeny Svetlanov

rec. 1991-3, Great Hall of the Moscow Conservatory, Russia. DDD

Olympia OCD 732 [72]

Volume 3

Symphony No 3 in A minor, Op 15 (1914)

Symphony No 13 in B-flat minor, Op 36 (1933)

Russian Federation Academic Symphony Orchestra/Evgeny Svetlanov

rec 1965 (3) ADD, 1991-3 (13) DDD, Great Hall of the Moscow Conservatory, Russia.

Olympia OCD 733 [68]

Volume 4

Symphony No 4 in E minor, Op 17 (1918)

Symphony No 11 in B-flat minor, Op 34 (1932)

Russian Federation Academic Symphony Orchestra/Evgeny Svetlanov

rec: 1991-3, Great Hall of the Moscow Conservatory, Russia. DDD

Olympia OCD 734 [77]

Volume 5

Symphony No 5 in D major, Op 18 (1919)

Symphony No 12 in G minor, Op 35 ‘Kolkhoznaya’ (Collective Farm) (1931-2)

Russian Federation Academic Symphony Orchestra/Evgeny Svetlanov

rec: 1991-3, Great Hall of the Moscow Conservatory, Russia. DDD

Olympia OCD 735 [78]

The first five volumes of this heroic project have now arrived in the shops. It is typical that it should be through the enterprise of Olympia – one of the ‘non-majors’ – that these digital recordings made a decade ago in Moscow should have found their way into general circulation.

This is a historically significant set, being the first single conductor-single orchestra traversal of the twenty-seven symphonies of Miaskovsky. By the way, am I wrong to render the name as ‘Miaskovsky’ rather than Olympia’s ‘Myaskovsky’? My preference follows the BBC style.

Leaving aside a small ‘print-run’ boxed set, with scanty notes, Olympia are responsible for issuing these premiere commercial recordings of symphonies 4, 13, 14 and 20. The others have been available in other versions on a tatterdemalion panoply of cassette, CD and LP over the years. The Thirteenth will be familiar, to those ‘in the know’, via an off-air recording of a BBC Radio 3 evening concert by the BBC Welsh Symphony conducted by Tadaaki Otaka on 9 November 1994. That fine scholar of Russian music, David Fanning, gave the introduction.

On the showing of these discs, newcomers to Miaskovsky as well as long-time adherents can place their faith in the series. The recordings are mostly digital, cavernously dramatic or honeyed, as in the great and sweetly sorrowing string hymn in the first movement of No 25. Svetlanov is pretty broad in his tempi and this has provoked criticism in some quarters. It has not troubled me except in the case of the Fifth, although I would be interested to have comments from those who know the full scores of the symphonies.

The First Symphony is Tchaikovskian. This is the stygian darker Tchaikovsky of Manfred (a work in which Svetlanov’s 1960s BMG-Melodiya recording with the USSRSO has yet to be beaten, though Yuri Ahronovich’s unissued LSO concert performance at the RFH in on 19 September 1978 came close. The same concert included one of the all-time great Francescas – any chance BBC Legends?). It is played with here out-and-out commitment typical of these Russians. Listen to the rasping crackling brass at 10:20 and 16:09 in the first movement – the rising of a tragic sun from deepest gloom. Miaskovsky was good at bass-heavy gloom (try the Seventh, Tenth and Thirteenth symphonies). Overall, the work reminded me somewhat of Scriabin’s six movement First Symphony. The larghetto is languidly paced – as is Svetlanov’s wont – and he paces the music appositely. The Allegro assai strides along athletic and hoarsely proud and without bombast. Nice stereo separation in the violin dialogue at 2:43. There is a great peroration to the finale, but earlier parts of it seem to be going through the motions. Otherwise, this is freshly envisioned music.

Symphony No. 25 (a work much under the shadow of the war with Germany) has a real charging attack in the allegro impetuoso third movement. This vigour is offset by a lovingly shaped and lovely melancholy at 02:15 et seq. Listen to the thunderous rap of the drum impact at 3:38 and the calamitously screaming trumpets emulating garish bugle calls at 6:30. This is definitely one of the works to return to among the twenty-seven. This digital version was issued, not long after the recording sessions, on Melodiya SUCD 10-00474 coupled with Symphony No 24. The only other of these Svetlanov digital tapes previously to surface commercially was that of Symphony No 17 – yet to be issued by Olympia. Neither of these old SUCD Melodiyas had widespread distribution. I managed to hunt them down via friends in the USA where there were still a few copies in the bigger shops. That apart, there is also a very old Melodiya LP of No 25 conducted by Konstantin Ivanov.

A sharply trudging, accented rhythm launches the first movement of the Second Symphony. This is a work from his time in Moscow at the end of his formal studies. It was not premiered until April 1915 by which time he was in action with the Russian Army. The concert was in St Petersburg with the Court Orchestra conducted by Hugo Warlich. This was quite a Miaskovsky event, as the tone poem Silence was also premiered on the same programme. The music has that archetypical black swooning, acid-hailing hysteria and craggy gait so characteristic of the composer and redolent of Rachmaninov’s Isle of the Dead, Tchaikovsky’s Fifth Symphony and Francesca (listen to the last five minutes of the first movement) and of Mussorgsky. The Adagio serioso is hesitant, melancholic and reflective with some recall, along the way, of the big slow movement of Rachmaninov’s Second Symphony. This disc has competition from Gottfried Rabl and the Vienna SO (Orfeo C 496 991 A) and a deleted Russian Revelation RV 10068 with Rozhdestvensky. Rabl is quick – 13:00, 13:44, 15:28. Rozhdestvensky – 14:05, 14:56, 15:23. Svetlanov – 13:52, 16:21, 16:41. I am not all sure about the ending of the work – rather perfunctory and abrupt – but this is an issue with the work, not with Svetlanov’s exegesis.

Three weeks to write in piano score and one week to orchestrate saw the Eighteenth Symphony emerge into a world racked with disappearances and show trials. Its mood is rambunctious like a boozy country fair, with echoes of Balakirev’s concert overtures and Mussorgsky’s Neva melancholy. There is also the jauntiness of Bax’s fake Slav Gopak and an ungenteel uproar that does remind you of Copland’s Rodeo and Billy the Kid more often than you might think. The idyll of the long lento (longer than the other two movements put together) gives way to a return to folksy capering and the gentle musing of the silver birch trees. The work was very popular in the Soviet Union and travelled far and wide, carrying its dedication to the twentieth anniversary of the October Revolution. It was even arranged for military band – a version that so impressed the composer that the Nineteenth was actually written for military band. A world away the British composer Joseph Holbrooke, during the same decade, wrote his Fifth (Wild Wales) and Sixth (Old England) Symphonies for brass band and military band respectively. Both made heavy use of national folksong.

The Third Symphony shudders forward, aggressive and driven with resentment and bitter bile. Melancholy even tinges the hints of brightness, as at 3:31 in the first movement. And in those trumpet gestures clawing upwards in spavined splendour we see both an inheritance from Scriabin and a legacy unmistakably embraced by Miaskovsky pupil, Khachaturian. If you know the emotional slough in which Bax’s Second Symphony heroically basks and rises from much of the first of the two movements will be familiar. It is at the same time both tense and pessimistic. The gloom has a tendency to stifle. Finally, listen to the rattle and gripe of the brass as the work stutters to the end of the 25 minute second and final movement. I compared the 1965 sound of this disc with the original Olympia Melodiya licensed disc OCD 177 and the deeper brass sounded noticeably better in the new transfer, but the slavonic steel soprano tones of the trumpet benches seem identical. There probably isn’t much in it. OCD 177 was AAD. This issue is ADD.

Until the mid-1990s few people knew anything about the Thirteenth Symphony except that it probably had to exist as there was a Twelfth and a Fifteeenth (both had been recorded). The Fourteenth had to wait until the Svetlanov set was issued to stagger blinking into the sunlight. The BBC commissioned the first performance in modern times from the BBC Welsh Symphony Orchestra conducted by Nimbus Rachmaninov and Mathias specialist, Tadaaki Otaka. It was revealed as a soul brother to No 3: equally gloomy of mien but tonally adventurous – so much so that, its clarity of orchestration aside, it suggests Bernard van Dieren in the Chinese Symphony. Frank Bridge (There is a Willow and Phantasm), Bax (specifically with reference to the Second Northern Ballad) and Berg are other triangulation points. Svetlanov gives us the world’s first ever commercial recording and makes what I take to be an expressionist success of it. This is a twenty-minute single movement essay in contemplation and stormy hammerhead clouds. The scurry of the strings and the crump and grump of the brass are impressive. Do not expect Tchaikovskian dramatics. This work is a denizen of the lower registers. Its length is comparable with the much more prominent Twenty-First, but otherwise there are few parallels. There is a studio cough at 11:55 in the second movement. Miaskovsky also regales us with a somnolent yet magisterial brass chorale, like a hymn to something without a garish atom in its being. The slowly melting relentlessly drift icy sheets of string sound (17:55) recall Pettersson – another pessimist or at least a traveller in the underworld with a mission to find moonlight; certainly not the dazzling glare of the sun. Yes, Petterssonians will want this fix of Miaskovsky. When the work ends (peters out really) it evokes the bedraggled motion of a fatigued clock. This is Lemminkainen in Tuonela without the Swan, without the high jinks of the Homecoming and with none of the amorous adventures with the Maidens of Saari.

Volume 4 again couples a great rarity with a work that is familiar, at least to Miaskovskians. The Fourth Symphony was planned as a work ‘quiet, simple and humble’. These qualities must have been channelled through a charcoaled mirror, for the mood is typically subdued for the first five minutes before rushing along in one of Miaskovsky’s scurrying scherzos – one part Rimsky and two parts utterly original Miaskovsky. The Sibelian upward striking flute glissandi amid brass calls are highly original. Note also the fractured trumpet fanfares echoing and the Sibelian woodwind at I – 9:40. This is a really striking coup. Listen also to how he unleashes the furies at 13:43. The Fourth is determined and stern, even when it moves with speed and fury. In track 3 at 18:00 Kaschei’s ecstasy is referred to – a momentary revelation. The work fascinates also for the first stirrings (5:48 track 3) of material to be developed in the tragic-heroic Fifth. These can be heard in the allegro energico finale. Also notable is some utterly unique dialoguing between dour brass and Sibelian woodwind. It ends with a totally surprising positive major key ‘blare’ right out of Tchaikovsky 5 and Rimsky-Korsakov.

The Svetlanov Eleventh Symphony ‘competes’ with Veronika Dudarova’s Moscow SO version on another time-expired Olympia (OCD133, issued in 1987!). Dudarova later recorded a respectable digital Sixth for Olympia in the 1990s, but she also gave the world a rather sleepy Glazunov Oriental Fantasy – not the best of Glazunov anyway. Dudarova’s Eleventh goes at a smarter clip than Svetlanov’s (31:09 rather than 34:46). The Symphony is certainly worth having and Svetlanov does it very well indeed. He breathes a ruddy life into the work, which is written in Miaskovsky’s most accessible style. The horn-lofted theme at 3:45 is tossed from section to section of the orchestra with confident abandon and it works … in spades. The offbeat strokes and stutters of the end of the first movement demonstrate Miaskovsky’s originality and his judgement. The Andante is delicate and warming, using the nostalgic Grieg-like sound familiar from the string serenades and Sinfonietta. The theme is a variant of the hurrying scherzo element from the first movement. The Precipitato-Allegro is in ingenious variation form – tightly put together rather than loquacious. The premiere was in Moscow on 16 January 1933. It is dedicated to Maximilian Steinberg, the son-in-law of Rimsky-Korsakov and no mean symphonist himself. His five are gradually being recorded by DG with Neeme Järvi directing. The First and Second are already available. And I wonder if John Williams got the threatening shark figure from Jaws through hearing the Lento preamble to the Allegro Agitato.

The Fifth Symphony (with the Violin Concerto) is the Miaskovsky work I would propose to ‘unbelievers’ and to those curious about the composer. Neither the Cello Concerto nor the famed Twenty-First matches its power of utterance. Unfortunately Svetlanov takes the work at a lumbering pace which, although revealing details often subsumed in drama, rather saps the work’s power except in the case of the Baba Yaga (Liadov) brevity of the folksy Allegro Burlando (III). The worst effect comes in the Allegro risoluto (IV) which for most of its 10:52 sounds tired. This is certainly the best recorded sound and the orchestral contribution is matchless, even in subtlety. Just listen to the long diminuendo at the end of the first movement. However, as a whole its incredibly distended 44:05 just does not cohere as it should. My preference would be for the 1980s Olympia (OCD133) of Konstantin Ivanov, in which the music moves with urgency (36:00) and is given a dramatic cutting edge. Only slightly behind comes the Balkanton CD 030078 at c 38:00, but you will have your work cut out finding this. It is worth it though. This has the work played by the Plovdiv PO/Dimiter Manolov. Then there is the Marco Polo 8.223499 – BBCPO/Edward Downes. This is the quickest of all at just short of 36:00 and is much easier to get.

The Fifth is the sort of work that would have you egging the orchestra on in front of your loudspeakers for all the world, like Beecham bellowing exhortation in his live BBCSO performance of the Sibelius Second. Think of Svetlanov’s interpretation as the counterpart of Bernstein’s 1980s Enigma. You will learn new things about the work, but you will miss its essential character.

The Twelfth Symphony was premiered in Moscow under the baton of Albert Coates who paid scant regard to the composer’s tempi. Illness kept the composer from the premiere – but perhaps fear of suffering at the hands of Coates what Rachmaninov had suffered from Glazunov at the first performance of the First Symphony had more to do with it. This is in the usual three movements, rather than the Fifth’s four. It has been recorded once before on Marco Polo with Stankovsky and the Czecho-Slovak RSO (8.223302). A dancing and sometimes poetic Slavonic folksiness (part Copland, part Glazunov, part Rimsky, part Bliss at 7:40 of the finale) plays through the pages of the big first movement rather paralleling the Eighteenth and Twenty-Sixth Symphonies and the third movement of the Fifth. The three movements have a programme appended: i. before the October Revolution, ii. the Struggle for new life and iii. Victory over the Kulak (wealthy landed classes) supremacy. Levon Hakobian attributes the bleak pessimism of the Thirteenth Symphony to Miaskovsky’s shame over the political compromises he made over the Twelfth. If there is a problem it is with the gauche programme not so much with the music which is alive with a well-lit imagination, though bombast puts in an appearance once too often in the Presto Agitato (II). Listen to the wind and string shivers at the end of the first movement for a few of the strengths and to the plainchant earnestness of the Allegro festivo (III, 3.40). Svetlanov makes more of this than Stankovsky. It is not top-notch Miaskovsky, but it is a not unattractive work if you are into 20th century celebratory Russian nationalism. It escapes the accidie of the conductor’s approach to the Fifth Symphony.

Economically, the digital recording sessions elided the works Svetlanov had already recorded. In the case of these five volumes this means that Symphony No 3 on OCD 733 is the 1965 Melodiya recording and is, of course, ADD rather than the predominant DDD norm for the cycle. This leaves the way clear for anyone who would like to offer the first complete digital cycle, but I don’t see that happening anytime soon.

This is a uniform edition with the stylised onion-dome cover illustration by Peter Schoenecker. Each volume will be identified by a different tint. Discographical details are pretty decently tackled, even if I could have wished that exact dates for the various sessions had been given. The best we get for the new digital series is 1991-1993. The analogue origins of the tapes of Symphony No 3 is declared with enviable candour twice over and you need not give it a second thought.

I noticed Olympia’s attention to accuracy when they call the series ‘The Complete Symphonic Works’. The two concertos are not included. The Cello Concerto is well known and multiply recorded, including by the world’s finest cellists. Olympia already have this work in their catalogue with the two cello sonatas. The glorious violin concerto used to be in the Olympia stable but toppled under the headman’s axe long ago. If you see the disc (Olympia OCD 134) second hand, don’t hesitate. Grigori Feigin (Karkhov-born and a David Oistrakh pupil) gives a grand performance and he is richly recorded in stereo. Oistrakh premiered the work and his 1940s mono recording is to be had on Pearl – and it sounds very good indeed from Decca shellac.

Olympia will now, I hope, look at completing their Vainberg cycle. There are quite a few gaps in the symphonic sequence. I also wonder if they could be persuaded to record the symphonies of Lev Knipper. Yuri Shaporin’s Russian nationalist Symphony of the early 1930s has compelling claims to attention, as also does Shaporin’s reputed masterwork – the major choral/orchestral piece On the Field of Kulikovo (the latter to words by Alexandr Blok). Svetlanov recorded that work on Melodiya …… The two symphonies of Lev Revutsky (recorded by Melodiya in the nineteen-sixties) should be worth dusting off, as should the two piano concertos by Ivan Dzerzhinsky.

Back to Miaskovsky … laurels and palms should be strewn under Olympia’s feet. When the Miaskovsky cycle is complete, it will outpoint the limited edition produced by Records International (RI). They will take one disc more than Jeff Joneikis’s RI box – seventeen rather than sixteen CDs. The notes (in French and German as well as English) are scrupulously written by Olympia’s regular, Per Skans. With such neglected music, we are greatly in Mr Skans’ debt.

Francis Wilson tells me that the plan is to issue the seventeen discs at the rate of two a month. By the late summer, the sequence should be complete.

My suspicion is that you will want all of these. If you would rather be more abstemious then or would like to dip a nervous toe in the water, then go for Volumes 1 and 4 first. Watch out for the later issues, all of which I hope to review here.

Rob Barnett

For further background reading, see Jonathan Woolf’s excellent Nikolai Miaskovsky A Survey of the Chamber Works, Orchestral Music and Concertos on Record

Help us financially by purchasing from

Notes on the current availability of the complete orchestral works:

After the release of the 5 volumes reviewed above, Olympia released a further four volumes of the complete orchestral works. With the faltering of Olympia releases, Alto (in partnership with Olympia, using the Olympia master pressings) periodically released the remaining Volumes 10-17. In 2021 Alto released a refurbished 14-CD box set of all 27 symphonies (Alto ALC3141). Included were the expert music notes by Per Skans, in a 36-page booklet, from the Olympia and Alto individual CDs.

See Rob Barnett’s and Gregor Tassies’ reviews of the further releases of Symphonies and orchestral works from Alto/Olympia: ALC1021-22 ~ ALC1023 ~ ALC1024 ~ ALC1041 ~ ALC1042-43 ~ ALC3141 (RB) ~ ALC3141 (GT)

In 2008 Warner Classics France released a 16-CD box set of the complete symphonies and other symphonic works, based on the same Olympia pressings (Warner Classics 2564 69689-8). The biggest failing of this release is that it did not include the expert notes included in the Alto ALC3141 collection. The documentation that was supplied was not comprehensive.

See Rob Barnett’s review of the Warner Classics 2564 69689-8 release.

The Alto ALC3141 14-CD box set is currently available at the links provided above at extremely reasonable prices, well under £55. The Warner Classics 2564 69689-8 16-CD box set is currently available, as CDs or download, on Amazon.co.uk and Presto Music, also at well under £4 a disc.

The individual Alto/Olympia Volumes 1-17 recordings are currently all available on Amazon UK, as are some recordings of individual symphonies and orchestral and concerto works. The individual Alto/Olympia Volumes 11-14 and 16 recordings are currently available on Presto Music.

Finally, an additional note from Nick Barnard regarding availability:

The complete cycle (equivalent to 14 CDs) may be bought as a download from Classic Select for only £6 – a remarkable bargain: https://www.classicselectworld.com/products/copy-of-myaskovsky-the-complete-symphonies-russian-federation-symphony-orchestra-evgeny-svetlanov-14-cds

The bit rates (MP3 or FLAC) are not clear and I have no idea how well tagged etc. the files are; I have the hard copies of these discs so have never downloaded this. I have bought various other things from Classics Select over the years and technically etc they are absolutely fine. So no reason to expect otherwise here and at that price it is surely worth a punt even if you’re not sure whether you like Myaskovsky.