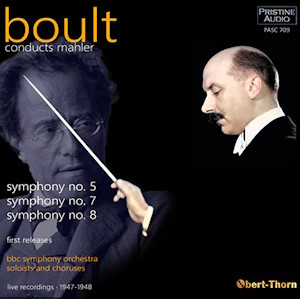

Gustav Mahler (1860-1911)

Symphony No. 5 in C-sharp minor

Symphony No. 7 in E minor

Symphony No. 8 in E-flat major, “Symphony of a Thousand”

BBC Symphony Orchestra/Sir Adrian Boult

rec. live (broadcast), 20 December 1947 (5); 31 January 1948 (7) BBC Maida Vale Studio No. 1, London; 10 February 1948, Royal Albert Hall, London (8)

Pristine Audio PASC709 [3 CDs: 228]

Between November 1947 and March 1948, in what was a very ambitious project for its time, the BBC Third Programme broadcast performances of all nine completed symphonies by Gustav Mahler. These came from a range of sources. Some were commercial recordings; one was a broadcast by an overseas radio station and five were concert performances mounted by the BBC. Of these latter, Bruno Walter conducted the London Philharmonic Orchestra in the First Symphony (not the BBC Symphony, as stated in the liner note). That performance has been available for a while on CD (Testament SBT1429); we haven’t reviewed it but it was referenced by my colleague Lee Denham in his comprehensive survey of recordings of the symphony. The remaining four performances were conducted by Sir Adrian Boult. He gave the UK premiere of the Third Symphony; that performance was issued by Testament a few years ago (review) and the other three performances are now issued by Pristine. I’m indebted to Jon Tolansky who very kindly provided me with details of all the broadcast in the series: I have appended them to the foot of this review.

Sir Adrian Boult’s name doesn’t spring immediately to mind when one thinks of Mahler interpreters. However, I looked at Michael Kennedy’s authoritative 1987 biography of the conductor and discovered that during his career Boult conducted seven of the nine symphonies (but not the Second and the Sixth) and the Adagio of the Tenth, chiefly during his years with either the City of Birmingham Orchestra or with the BBC Symphony. In addition, he led performances of Kindertotenlieder, Lieder eines fahrenden Gesellen (he also recorded both cycles with Flagstad and the Vienna Philharmonic in 1957), Das Lied von der Erde (giving the second UK performance of the work, in 1930) and even Das klagende Lied. The latter was a 1914 performance in which the accompaniment was provided not by an orchestra but by two pianos; even so Kennedy speculates, probably correctly, that this may have been the first time the cantata was played in the UK. Kennedy quotes a remark which Sir Adrian made late on in his life to his EMI producer, Christopher Bishop: he said of Mahler that it was ‘odd music, but great fun to conduct’.

Before considering the performances, I should say a word about the sources. When I reviewed the Testament release of the Third Symphony I related the provenance of that recording, as related by Jon Tolansky in his booklet essay. Edward Agate, a musicologist, made off-air recordings onto acetate discs of the broadcasts of all the Mahler performances in the 1947/48 series that were concert or live studio performances. Years later, and quite by chance, Tolansky came upon a pile of some 200 such discs, including these Mahler performances, in a Manchester record shop and, having identified what they were, bought the whole collection. This discovery was one of the factors that led to the foundation of the Music Performance Research Centre, now Music Preserved, to which Tolansky donated his Manchester treasure trove. Music Preserved have made the Mahler discs available to Mark Obert-Thorn, who has restored them. He explains in a note that Agate recorded off-air using two cutters but even so there were some gaps when sides were changed. As part of his restoration work, he has patched these small gaps. Using digital editing and other modern techniques, he has, he says, “ameliorated the problems to some degree, allowing the performances to be heard finally in something which has, hopefully, a degree of body and detail belying their AM radio/home recorded acetate origins”. The recording of the Eighth has been available in the past as an unrestored download from Music Preserved but the Fifth and Seventh have never been available until now. These two symphonies were recorded in the BBC studios and broadcast either live or ‘as live’.

Right at the start of the Fifth symphony there’s a bit of a slip by the principal trumpeter who mis-pitches the last note in his solo (0:25) – though the note he actually hits does fit harmonically. Thereafter, Boult takes the funeral march at a fairly steady pace; the effect is solemn and weighty. When the much quicker episode in B-fat minor arrives (5:41), Boult injects the right degree of urgency, making the passage suitably turbulent. Overall, I think his way with this movement is convincing. The Stürmisch bewegt second movement emerges strongly; the conductor’s conception of the music is virile. In the passages where Mahler eases back, Boult conducts stylishly and with empathy for the music; I think he demonstrates a good understanding of the idiom. When the chorale is reached (11:45) there’s grandeur in the performance, albeit the sonic limitations of the recording rather limit the effect. The huge Scherzo appears slow to burst into life; the opening pages seem rather sober. In truth, Boult’s reading is something of a mixed bag: at times his approach seems too straight-faced but in other passages he conducts with vigour and gets real lift in the rhythms. In the celebrated Adagietto the harp part is nicely prominent – by which I mean it can be clearly heard without being too obtrusive. At first, Boult’s approach is dignified but when the mood becomes more ardent (4:17) he responds very well. I think he shapes this movement well and, despite the limitations of the recording, it’s clear that the BBC Symphony members play with sensitivity. Rather as with the Scherzo, the Rondo – Finale seems a bit of a slow burn. After the little series of woodwind and horn solos, the music seems slow to take off (from 0:49); frankly, Boult’s approach is a bit cautious. Things start to look up with the string fugato (1:34); Boult injects pace, as called for by Mahler. From 6:14 the performance has no little vitality. There are times in this finale where Mahler eases off and I do have the impression that Boult takes these episodes a bit too steadily but the Rondo material itself is always presented in a lively fashion. The last couple of minutes (from 15:09) blaze satisfactorily though Boult keeps the music on a fairly tight rein, not whipping up a high-speed dash for the finish line as many conductors do nowadays. To be honest, I’ve heard many accounts of the Fifth’s last movement that are more exuberant than this one.

In the last analysis, Boult’s reading of the symphony, though disciplined and very musical, didn’t have me on the edge of my seat. That said, we’ve become very accustomed to the highly-charged interpretations of conductors such as Bernstein, Solti and Tennstedt; perhaps such performances unfairly skew our judgement of the performance of Boult, who came from an earlier tradition and who, in any case, wouldn’t have conducted the work in such an intense, heart-on-sleeve fashion. I wonder if it was his first performance of the symphony; Michael Kennedy doesn’t mention any earlier – or later – traversals in his biography. The BBC Symphony Orchestra aren’t flawless in the face of this demanding score but they do a pretty creditable job. Unfortunately, the limitations of the off-air recording mean that a lot of inner detail is lost (for example, the quiet contributions of the bass drum in the first movement) and there’s a fair degree of distortion at many of the climaxes. Nonetheless, we can get a very good idea of the overall design of Boult’s interpretation.

Some six weeks after playing the Fifth, Boult and the BBCSO presented the Seventh. No other Boult performances of this work are listed in Michael Kennedy’s biography so I presume this was the first – and probably the only time – that he conducted the work. I suspect the work was little known in the UK at the time though Jon Tolansky has told me that Sir Henry Wood conducted it in 1913 – very early in the work’s performing history – and that Anton Webern conducted the BBCSO in a performance in 1934; I bet that was a fascinating occasion. I wonder how many recordings there may be of earlier performances of the Seventh than this Boult traversal. I know of – but have not heard – recordings by Scherchen and Rosbaud from the 1950s, both of which are mentioned by Tony Duggan in his survey of recordings; but this Boult performance may be the earliest that’s available on disc. Mahler’s orchestration is especially inventive in this symphony and I wondered how much detail would be audible in this off-air recording made 76 years ago. I was surprised and delighted: in sonic terms, the Seventh fares better, I think, than the Fifth. .

Boult launches the first movement auspiciously. When the march music first appears (1:44) his tempo is surely too deliberate. However, at 3:48, as demanded by Mahler, the tempo picks up and thereafter I consistently found Boult’s pacing very convincing. The recording gives us a good impression of Maher’s scoring although not every detail is apparent, of course; what is apparent, though, is that the BBCSO has been very well prepared. I’d summarise Boult’s account of the first movement as cogent and well played. Nachtmusik I is intelligently paced and the conductor demonstrates a fine degree of attention to detail. The passages where Mahler’s scoring is particularly shadowy (for instance 7:16 to about 8:10) come over well. Boult seems to me to have an excellent feel for the idiom. The strange, phantasmagorical music of the Scherzo also fares well. Boult and his orchestra convey the unorthodox spirit of the music. Once again there’s evidence of excellent attention to detail and the playing is artfully pointed. In Nachtmusik II the important colourings provided by the guitar and, especially, the mandolin register really well. The interpretation and playing seem to me to be stylish and precise. The Rondo-Finale is quite steady at first – rather too steady, I feel – but Boult soon gets into his stride. If I’m honest, I’ve heard quite a number of conductors invest this movement with greater pace and sparkle. However, I’m wary of judging the performance through the prism of the evolution of Mahler performance over the last fifty years or so. Boult charts a steady course but it’s very important to acknowledge that he keeps a firm hand on the tiller in music that can become over-exuberant or even vulgar; he’s in control throughout. The often-uproarious scoring presents a bit more of a challenge to the orchestra than was the case in the previous movements but they cope very well and turn in a highly creditable performance. The symphony is a huge challenge for an orchestra and conductor even today. In 1948 it was much less familiar fare; Boult and his players deserve huge credit for this performance. I was impressed.

At the end, the BBC announcer tells us what we’ve just heard in clipped received pronunciation, which is very much of its time. During both the Fifth and Seventh performances I heard a few stray coughs and also some shuffling between movements. I’m guessing that no audience was present – there’s no applause – and these few extraneous noises aren’t distracting; rather, they remind us that these were live performances.

The performance of the Eighth must have been a huge undertaking. Though this wasn’t the last broadcast in the series – the symphonies were broadcast in chronological order (see below) – the Eighth was the last concert performance and must have been seen by many as the pinnacle of the series. Logistically, it was very ambitious, involving four adult choirs and two children’s choruses. Part II was sung in English – I don’t know who made the translation. It may well be that English was used for the practical reason that the amateur singers in the choirs would have quite enough to do mastering the music without also having to learn it in German. In fairness, though, I believe Boult’s 1930 performance of Das Lied von der Erde was also given in English; perhaps accessibility on the part of the audience was therefore a factor. In the track listing of Part II, Pristine have used German titles because, they say, “not all of the English translation was decipherable”. That’s indeed true.

I’ll be honest and say that I approached this recording with a little trepidation. Realistically, the Royal Albert Hall was the only feasible choice for a London venue for a work on this scale in 1948 – the Royal Festival Hall was not yet built – but it must have presented the BBC engineers with a stiff test. Not only did they have to present satisfactorily forces that were very large but also they had to accomplish that task in a building with a huge and notoriously resonant acoustic (the “flying saucer” acoustic panels, suspended from the ceiling of the hall to ameliorate the echo lay many years in the future). Only recently, I reviewed a set that included a performance of Das klagende Lied given in the Royal Festival Hall in 1956. The BBC engineers had struggled with the forces required for that work, so I wondered what the sound would be like on a broadcast given eight years earlier with much larger forces and in a much bigger acoustic. In truth, the results significantly exceeded my expectations. Of course, the sound has undeniable limitations – one would expect that – but the 1948 engineers did a commendable job.

Part One of the symphony is conducted with great urgency by Boult – he takes a mere 20:31. Just as a point of reference, a modern live performance conducted by Osmo Vänskä, which I’ve recently reviewed, takes 22:59 and I thought Vänskä was pretty swift. (Boult takes just 78:47 for the symphony as a whole.) If Boult’s interpretation has a fault, it’s that there are times when I felt he could have relaxed a bit. That said, I admire the energy and urgency, especially when you consider he was conducting a large, composite chorus of amateur singers. A round of applause, too, for the children who make a sterling contribution – they really cut through in the ‘Accende’ episode and again when they introduce the ‘Gloria Patri’. Unfortunately, in the closing pages of the movement the engineering simply couldn’t contain the vast sound; the recording is blurred and overloaded – though you can tell the point at which the extra brass join the fray. The effect must have been tremendous in the hall itself; no wonder there’s applause when the movement ends.

At the start of Part Two, we can hear how well Boult has prepared his orchestra: they give an impressive account of the long orchestral introduction. Some may feel that Boult is too deliberate in the opening pages but on the other hand, he establishes a sense of mystery and a strong atmosphere. And when the music becomes more passionate (from 4:18) he’s quick to respond. I’m afraid that the next passage, involving the male voices of the choir, is considerably less successful. The singers are very indistinct – I challenge anyone to discern their words – but worse still, they sing the music legato and their tuning is fallible. Frankly, this is a low point in the performance. Matters improve with the solo contributions of George Pizzey and Harold Williams. The former is hampered by too cautious a tempo set by Boult – as a result, the music doesn’t convey the “ecstasy” which Pizzey’s English text mentions a few times. Both singers do well, though. The third male soloist is tenor William Herbert. He is a very English-sounding tenor and, as such, not entirely ideal for the role of Doctor Marianus but he does well enough and sings with clarity. The two contraltos, Mary Jarred and Gladys Ripley make fine and very dependable contributions. I’m afraid I’m not at all impressed with the two principal sopranos, Elena Danieli and Dora van Doorn. They are clearly over-taxed at times by their roles in Part I and I don’t care for their rather light and pretty voices in Part II. Emelie Hooke is rather better; she sings the small but crucial role of Mater Gloriosa well enough. The choirs do well once we’re past that rather unfortunate first episode, though at times the quiet singing is too recessed: that may be due to the recording but I wondered if perhaps only part of the combined chorus was involved at certain points. Boult’s direction of the music is sure-footed and though I might quibble with some points of detail the overall sweep of his direction is impressive. At the very end of the symphony everyone, singers and orchestral players alike, is clearly straining to contribute to Mahler’s heaven-storming vision. Inevitably, the recording can’t cope, but one still gets a good sense of the occasion. It comes as no surprise that there’s an ovation at the end; it must have been an overwhelming experience for the audience.How many of them had ever heard Mahler’s Eighth, I wonder?

These three Mahler performances are fascinating to hear. We live in an age when we are almost saturated with Mahler’s music and opportunities to hear it, both live and through recordings, are legion; indeed, arguably, we’ve become too familiar with it. These performances take us back to an age – less than 80 years ago – when Mahler’s music was far less well known to audiences and, indeed, to musicians. It was hugely enterprising of the BBC to broadcast all nine of his symphonies over a period of some four months. The viability of the project depended greatly on the willingness of Sir Adrian Boult to rehearse and perform no less than three enormously demanding symphonies. As Michael Kennedy observed in his biography: “These Mahler performances came a decade before the British revival of interest in the composer. Many another conductor would have cried from the publicity office ‘Look what I’m doing for Mahler here!’ Boult just conducted it.” And perhaps we shouldn’t wonder at Boult’s ability to present a complex score like the Seventh symphony so cogently: after all, this was a man who had already conducted, for example, the UK premiere of Wozzeck – and who was to conduct it again in 1949 (review). So, this set stands as a fine testament to one of the many and varied strands of Boult’s work with the BBC Symphony Orchestra.

As I’ve indicated, there are limitations to the recordings. However, one can still get a very good idea of the overall sweep and structure of Boult’s interpretations. We can also hear more than enough to admire his attention to detail and his preparation of the orchestra in all three works. I noticed quite a degree of surface hiss in the Fifth symphony, especially in the first two movements but overall, the transfers are smooth. It seems to me that Mark Obert-Thorn has done a very good job with the source material.

Inevitably, this is something of a specialist issue but Mahler devotees and admirers of Sir Adrian Boult will find it fascinating.

John Quinn

Previous review: Lee Denham (February 2024)

Availability: Pristine Classical

The BBC Mahler broadcasts 1947-48

6 November 1947 Symphony No 1 London Philharmonic / Bruno Walter (Concert in Royal Albert Hall, London) (Testament SBT 1429)

17 November 1947 Symphony No 2 ‘Resurrection’ Minneapolis SO / Eugene Ormandy (Commercial recording)

29 November 1947 Symphony No 3 BBC Symphony / Boult (UK premiere) (Testament SBT2 1422 – review)

12 December 1947 Symphony No 4. New York PSO / Walter (Live commercial recording 1945 – Sony – review)

20 December 1947 Symphony No 5 BBC Symphony / Boult

31 December 1947 Symphony No 6 Orchestra of the Nordwestdeutscher-Rundfunk / Hans Schmidt-Isserstedt

31 January 1948. Symphony No 7 BBC Symphony / Boult*

10 February 1948 Symphony No 8 BBC Symphony / Boult

13 March 1948 Symphony No 9 Vienna Philharmonic / Walter (Live commercial recording, 1938 – Pristine PASC 389 – review)

*Remarkably, on 12 January 1948 the Third Programme had broadcast another performance of the Seventh, given by the BBC Northern Orchestra augmented by members of the Liverpool Philharmonic Orchestra, conducted by Karl Rankl

Soloists and choirs (Symphony 8)

Magna Peccatrix – Elena Danieli (soprano); Una Poenitentium – Dora van Doorn (soprano);

Mater Gloriosa – Emelie Hooke (soprano); Mulier Samaritana – Mary Jarred (contralto);

Maria Aegyptiaca – Gladys Ripley (contralto); Doctor Marianus – William Herbert (tenor);

Pater Ecstaticus – George Pizzey (baritone); Pater Profundus – Harold Williams (bass)

BBC Choral Society; Luton Choral Society; Wallington Choral Society; Watford and District Philharmonic Society; Lambeth Schools’ Music Association Boys’ Choir; Boys of Marylebone Grammar School