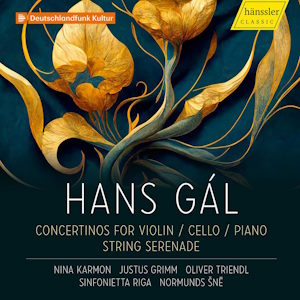

Hans Gál (1890-1987)

Concertino for Cello and Strings Op. 87 (1965)

Concertino for Piano and Strings Op. 43 (1934)

Concertino for Violin and Strings Op. 52 (1939)

Serenade for Strings Op. 46 (1937)

Nina Karmon (violin), Justus Grimm (cello), Oliver Triendl (piano)

Sinfonietta Riga/Normunds Šnē

rec. 2023, Reformation Church, Riga, Latvia

Hännsler Classic HC23049 [69]

I recently reviewed a disc of music by the German composer Joseph Suder. He was born two years after Hans Gál (article), and was almost equally long-lived. Both composers came to prominence in the 1920s, each with an opera: Suder’s Kleide macht leute (Clothes Make the Man), and Gál’s Die Heilige Ente (The Holy Duck). After 1933, their lives diverged sharply. Suder continued a successful career in Munich, while Gál, of Jewish descent, had to flee to Britain in 1938. The works on this disc encapsulate his career.

Serenade for Strings was written a year before Gál’s emigration to Britain. It easy to see why it was popular with British audiences in the 1940s, with wide intervals, intimate knowledge of writing for strings and overall geniality (one is reminded of Cecil Armstrong Gibbs, an Englishman). These qualities are especially notable in the Cavatina movement. The final Rondo is more polyphonic, with some Alt-Wien feeling.

The Concertino for Piano and Strings comes from three years earlier. The work exemplifies one of Gál’s major traits: the ability to use classical forms not in the usual Neo-classical way. The opening Intrata is typical of his naturally positive outlook. The Siciliano is notable for the use of solo piano versus a few of the strings, and for its underlying element of sadness. The Fuga combines these elements into a basically positive conclusion.

Only two years separate the composition of the String Serenade and the Concertino for Violin and Strings, but there is a stark emotional distance, likely due to Gál’s forced emigration. In two linked movements, the Concertino starts with serene pastoral music. There is especially fine writing for the soloist, but soon this is repeatedly interrupted by “march-like bass figures”, to quote Mathias Corvins’s notes, before ending with a tragic cadenza. The second movement is based on an old dance that Gál found in the British Library. It is more cheerful, but not without somber moments.

The much later Concertino for Cello and Strings is a masterwork. It shows Gál knowledge of the instrument, also demonstrated in several other pieces during his career. The work begins with a cadenza for the cello, followed by contrasting string material. Gál successfully combines these two elements in an emotional middle section. The central Adagio movement strikes even deeper, although there is a slight lightening of the texture at the end. The last movement also has an important cadenza, but humor, the primary element here, gives a satisfactory end to the Concertino.

In the past, I have discussed pianist Oliver Triendl’s talents as soloist and chamber player. The Concertino for Piano and Strings gives him a chance to demonstrate both areas of his talent in a single piece. Justus Grimm does equally well with the Cello Concertino, especially in the Adagio. Violinist Nina Karmon is also to be commended. Conductor Normunds Šnē does an excellent job with the Sinfonietta Riga. He makes them sound twice as powerful as the number of players would suggest. This is a fine addition to the ever-growing Gál discography.

William Kreindler

Help us financially by purchasing from