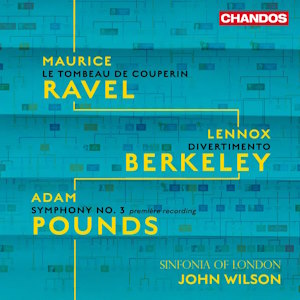

Maurice Ravel (1875-1937)

Le Tombeau de Couperin (1914-1917, 1919)

Lennox Berkeley (1903-1989)

Divertimento in B flat major, Op.18 (1943)

Adam Pounds (b. 1954)

Symphony No.3 (2021)

Sinfonia of London/John Wilson

rec. 2022, Church of St Augustine, Kilburn, London

Chandos CHSA5324 SACD [66]

This remarkable programme aims to draw a line between Maurice Ravel and Adam Pounds by way of Lennox Berkeley, with Nadia Boulanger in the background. Berkeley did not formally study with the French master, but they had “firm bonds between mentor and protégé”. Through this relationship, he was introduced to the artistic circles in pre-war Paris, and he did take lessons from Nadia Boulanger. The liner notes (from which I will quote, with thanks) say: “Ravel admired the sensuous side of Berkeley’s music when he was shown it, but felt it lacked technical finesse.”

First up is Ravel’s Le Tombeau de Couperin (The Tomb of Couperin), originally a piano suite. The composer insisted that it was “a tribute not so much to Couperin himself as to Eighteenth Century French music in general”. The movements deploy “modern French harmonies”, but their titles nod to the dances which clavecinists played in the 17th and 18th century. The work, penned during the First World War, is not depressing or even elegiac, but each movement is dedicated to one of the Ravel’s friends killed in the fighting.

Ravel orchestrated Le Tombeau in 1919, omitting the last two movements, the Fugue and the Toccata. The orchestral suite was first performed on 28 February 1920 by the Pasdeloup Orchestra conducted by Rhené-Baton. Kenneth Hesketh orchestrated the neglected movements in 2013 for the same orchestral forces as Ravel. The Sinfonia of London give a wonderful performance, and especial magic is created by the woodwind department.

Lennox Berkeley’s Divertimento for orchestra, commissioned by the BBC, is dedicated to his teacher, the redoubtable Nadia Boulanger. The piece is in four movements: Prelude, Nocturne, Scherzo and Rondo. It was premiered at the Bedford Corn Exchange on 1 October 1943 by the BBC Symphony Orchestra under Clarence Raybould. Critic Alan Frank (cited by Peter Dickinson in the sleeve notes for the Lyrita disc SRCD.226) sums the piece well. He says that Berkeley found “a light way of expressing serious thought […] illuminated by a Latin clarity”. Alec Robertson (The Year’s Work in Music, 1948-49) writes: “[The] Divertimento […] is, at least in the outer two movements, an excellent answer to the objection that the contemporary composer leaves out so many things that people enjoy and includes so many that they do not.”

There will always be a matter of dispute whether to regard this work as “light music” or something a little more serious. Certainly, the melancholy slow movement and the astringent scherzo go beyond what would have been standard on Friday Night is Music Night. The Sinfonia of London gives a powerful performance.

Between 1946 and 1968, Lennox Berkeley was Professor of Composition at the Royal Academy of Music. Adam Pounds had sent some early scores to him, including his prize-winning Oboe Quartet, by way of “self-introduction”. Berkeley retired from teaching, but was prepared to offer Pounds “a little general advice” beginning in 1976. This arrangement lasted for three years. The booklet tells us that “Berkeley constantly impressed […] the importance of always composing with the needs of performers in mind, and above all with clarity and economy: ‘write only the notes you need!’ was his defining mantra”.

I am beholden to Mervyn Cooke’s liner notes for the background of Adam Pounds’s Symphony No.3. It grew out of his reaction to the succession of national lockdowns engendered by the Covid-19 pandemic beginning early 2020. Actual composition was between February and May 2021, during the second major lockdown. Pounds notes that he has captured the “sadness, humour, determination and defiance” which was the emotional response by the public at large.

The Symphony, conceived in four contrasting movements, reflects those sentiments. The small orchestra is devoid “of vast ranks of percussion, or multiple brass instruments”. The work is tonal, with little in the way of harsh dissonances and few modernistic melodic or rhythmic devices.

The opening movement presents three ideas that are occasionally Ravelian in mood and at times echo the redoubtable “Cheltenham Symphony” – and none the worse for that. It creates a sense of “the dawning of a new, uneasy day”. There are “two interruptions by fast, powerfully dynamic music suggestive of what Pounds has termed ‘a driving force of determination’”. The second movement is a “waltz”. Cooke writes that it is in the “well-established tradition of unsettling danses macabres to which composers as diverse as Saint-Saëns, Britten and Shostakovich memorably contributed”. I am not sure just how ghoulish I found it. It is certainly a tour de force of orchestral writing, which, dare I say, could easily become excerpted on Classic FM.

The heart of the Symphony is the slow Elegy dedicated to all those who lost their lives during the pandemic. I am not a fan of Bruckner’s music, but I get Pounds’s point that it has the “strong influence” of that composer. It is quite beautiful and deeply moving. The finale, which projects “defiance”, opens with a march that nods to Shostakovich. Echoes of earlier movements emerge, bringing the symphony to a fulfilling and bold conclusion. Whatever the impact of Covid-19 on this work, it is filled with optimism and never gives in to hopelessness. It is a splendid addition to the British symphonic repertoire.

The performances, authoritative and satisfying, are complimented by an outstanding sound recording. Mervyn Cooke’s programme notes (in English, German and French) are helpful at all times. Resumes of the Sinfonia of London and John Wilson are included.

This noteworthy disc explores three fulfilling works by composers interconnected by pedagogical history.

John France

Help us financially by purchasing from