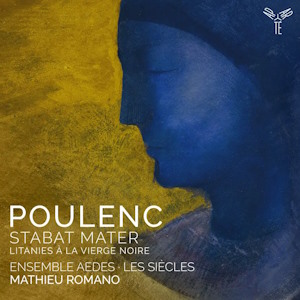

Francis Poulenc (1899-1963)

Litanies à la Vierge noire. Notre Dame de Roc-Amadour, FP 82 (1936)

Clément Janequin (1485-1558)

O doulx regard, o parler gratieuz

Francis Poulenc

Stabat Mater FP 148 (1950-51)

Marianne Croux (soprano)

Louis-Noel Bestion de Camboulas (organ)

Ensemble Aedes

Les Siècles / Mathieu Romano

rec. 2022/23, Théâtre Impériale, Compiègne; Royaumont Abbey, Val-d’Oise, France

Texts & translations included

Aparté AP323 [45]

Whilst one can’t overlook the short playing time of this disc, I hope that prospective purchasers won’t be deterred: not only are the performances very fine but there’s also a satisfying logic to the programme planning.

On the face of it, the short piece by Clément Janequin has no significant connection with the two Poulenc pieces. After all, it’s a secular chanson, probably written in the 1520s or 1530s. It is laid out for four voices and the text is one of courtly love. However, Mathieu Romano justifies its inclusion on two grounds. Firstly, he points out that Poulenc regarded the music of the Renaissance French composer highly. Secondly, Romano speculates that there may be a double meaning behind the text: “it could refer not only to a man’s love for his lady, but also to mankind’s love for the Virgin Mary, as an icon but also as a human being”. It’s a speculative argument but I certainly wouldn’t dismiss it. If one accepts Romano’s thesis then the piece fits in nicely between Poulenc’s two Marian works. In any event, the chanson is a little gem and it’s beautifully sung by the members of Ensemble Aedes. I think the juxtaposition of the Janequin and Poulenc pieces works well. (Significantly, the Janequin was recorded live in concert along with the Stabat Mater in two concerts in the Théâtre Impériale, Compiègne in October 2022; so, Romano hasn’t just dropped a studio recording of the Janequin into the programme.)

There are links between the two Poulenc works, not least the fact that both were composed in response to the sudden deaths of friends of the composer. As Nicolas Southon reminds us in his booklet essay, Poulenc had strayed from his childhood Catholic faith for many years until a cathartic event in 1936. His friend and fellow composer Pierre-Octave Ferroud (1900-1936) was killed in a road accident in August of that year. Within a matter of days, Poulenc made a visit to the town of Rocamadour and to the shrine of the Black Virgin. That very evening he began work on the Litanies à la Vierge noire, completing the score within a week. The work is scored for three-part female choir and organ, though I didn’t know until I read Southon’s note that the first performance, conducted by Nadia Boulanger, was sung by male and female voices. The present performance was recorded – under studio conditions, I think – in the refectory at Royaumont Abbey. This former Cistercian abbey was established in the thirteenth century, I believe, and is located near Asnières-sur-Oise in Val-d’Oise, just north of Paris. The abbey refectory boasts a Cavaillé-Coll organ. I leaned from the website of the Royaumont Abbey Foundation that the instrument was designed in 1864 for the villa of a rich industrialist, located on the shores of Lake Geneva; it was brought to Royaumont in 1936. It sounds terrific here.

The Litanies are sung here by eighteen singers, six to a part. The choir’s music is in many ways simple in design – though highly sophisticated at the same time – and the writing, though beautiful, is fundamentally austere in nature. The organ is used primarily for dramatic effect. The singers are disciplined and their tone is ideal for the music. Organist Louis-Noel Bestion de Camboulas makes a superb contribution and Florent Olivier’s engineering maximises the stark contrasts between the organ and the voices, which is what Poulenc intended. This is a magnificent performance, which sounds authentically French. I noticed in the “small print” of the booklet credits that the performance uses the autograph manuscript of the score, which is housed in the Bibliothèque nationale de France. I wonder if this implies that there are some discrepancies between the manuscript and the published score. Sadly, the notes are silent on this point.

The Stabat Mater was also prompted by the unexpected death of another of Poulenc’s friends, in this case the artist and designer Christian Bérard (1902-1949). I was intrigued to learn from Nicolas Southon’s notes that “possibly” Poulenc may have been inspired by the example of his friend, Lennox Berkeley. Berkeley had composed a setting of the same text in 1947 (review). After I’d finished my listening to this present recording, I found, by chance, a fascinating article by the conductor Peter Broadbent on the website of the Lennox Berkeley Society in which he compares and contrasts the settings by Poulenc and Berkeley. I’m not sure when Berkeley’s work was premiered and, therefore, whether Poulenc had heard it by 1950 when he began work on his own setting; it’s perfectly possible that Berkeley sent him a score. Berkeley’s work is scored for just six singers and an ensemble of 12 players; so, the scale is more intimate than Poulenc’s work. However, it’s noticeable that both composers produced succinct settings, each lasting just over 30 minutes; in neither work is a note wasted.

Poulenc scored his Stabat Mater for solo soprano, five-part choir (SATBarB) and orchestra. In this performance, the choir numbers 36 (7/7/7/7/8). I’ve detailed the numbers for a deliberate reason. I own a couple of earlier recordings; a very good 1984 performance conducted by Serge Baudo and an excellent 2012 version conducted by Daniel Reuss (review). The Baudo performance uses, so far as I can judge, a full-sized choir. Reuss uses 47 singers. His recording comes closer to the sense of intimacy that we can experience on this new recording by Ensemble Aedes. However, it seems to me that the newcomer has the edge in that respect, especially when you factor in the soft-grained sound of Les Siècles.

Poulenc sets the full text of the Stabat Mater, though he combines some of its twenty three-line stanzas, or tercets, so that his work has twelve movements. All of these are quite short and the result is a compressed, sometimes terse, setting. The composer sets a challenge to conductor and performers by varying the music according to the emotions expressed in each tercet. Thus, the performers need to adapt, often quite quickly, to many different modes of expression. The present performance is excellent in that respect. Indeed, it’s excellent in every respect. The singing and playing are incisive in all the biting, dynamic episodes; the bittersweet lyrical sections are equally well done. I like very much the warm, expressive singing of soprano soloist Marianne Croux; she seems ideally cast and I wouldn’t care to express a preference between her and the equally fine Carolyn Sampson who does the honours for Reuss. Poulenc’s Stabat Mater is a wonderful, eloquent work. I sometimes think it is unfairly overshadowed by his later setting of the Gloria. Mathieu Romano conducts a performance which does full justice to Poulenc’s inspiration.

At the end of the disc something very strange happens. The last track is the concluding section, ‘Quando corpus’, of the Stabat Mater. According to the booklet, this plays for 5:11; in fact, the music stops at 3:55. I was busy making a note of that and omitted to stop the disc from playing; indeed, I assumed it had stopped of its own accord. To my surprise, after a long gap, another piece of unaccompanied choral music begins at 5:12. I can’t identify the piece but it’s a polyphonic French chanson. At first, I thought that O doulx regard, o parler gratieuz had been tacked on again by mistake, but it’s not that piece. It sounds rather similar, though, and I wonder if it’s another piece by Janequin. It plays for a few seconds over two minutes, meaning that the final track lasts for 7:19. Was the inclusion of this ‘encore’ an editing error? If so, the result is very pleasing, especially as the significant gap means there’s no intrusion onto the end of the Poulenc.

This is an excellent and well-presented CD, which I enjoyed very much. As I’ve indicated, the standard of performance is extremely high. The recorded sound from both venues is excellent and the documentation is very good. Pairing together the Stabat Mater and the Litanies à la Vierge noire is very logical. If the programme appeals you can invest with confidence, despite the short playing time.

Footnote

We made an enquiry, via Aparte’s UK distributors to see if any light could be shed on the unexpected additional music which, after a gap, follows the Stabat Mater. We were told: “it’s a ‘ghost track’ of the musicians of the orchestra singing with the choir, which they did as an encore during their concert tour. It is indeed a piece [unidentified] by Janequin”.

Help us financially by purchasing from