Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart (1756-1791)

Sonatas for Piano and Violin

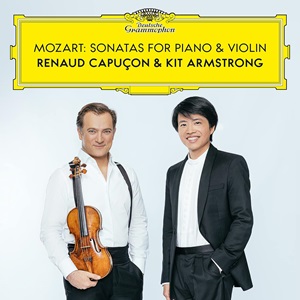

Kit Armstrong (piano), Renaud Capuçon (violin)

rec. 2022, Teldex Studio, Berlin, Germany

Deutsche Grammophon 4864463 [4 CDs: 241]

I was surprised to see the cover of this CD set read “Mozart Sonatas for Piano and Violin.” Many disgruntled pianists are well aware that this is how Mozart himself styled these pieces, so with memories of past slights in mind, it was pleasant to see a modern record company being this careful with their product. As it turns out, there are several CD sets that get it right; Radu Lupu/Szymon Goldberg; an older issue of Barenboim/Perlman (a recent re-release reverses the order, sadly), and Pappano/Sitkovetsky are three correctly titled recordings that pop up via a quick Google search.

This may seem like a petty focus with which to begin a review, but upon opening the CD booklet for this new set, I came face to face with an essay titled “Not violin sonatas” by Raoul Mörchen. The writer details the tale of Mozart and violin music, reminding us that the boy played sonatas with Papa Leopold standing over his shoulder; he wrote more violin sonatas than any other type of chamber music, and the six sonatas K. 301-306 (publ. 1778) were in fact were the composer’s “op. 1” long before Herr Köchel got any ideas about cataloguing Mozart chronologically.

For those unfamiliar with the music, the violin does in many places play a subordinate role, a situation that explains the gap in many violinist’s repertoires, which often jump directly from Bach and Handel to Beethoven. “Subordinate” in this case does not mean that the music played by the violinist is uninteresting or unimportant, but merely that the scores generally go something like this: the pianist plays a melody, the violin comments vigorously and rhythmically, usually doubling the left hand of the pianist. The violinist then gets to play the melody, but again is doubled, the pianist playing along (although occasionally, this occurs with the pianist playing harmony). When the tune returns for the pianist, the violinist will get to saw away on a bit of Alberti bass. The pianist’s part in allegro movements is usually black with 16th notes (Mozart was capable of writing some nasty arpeggiated and scale figures), while the violinist never has to tackle anything too frightening. This is why pianists generally avoid these pieces; learning and performing them is similar to learning and performing one of the solo sonatas, with the added complication of ensemble. Violinists mostly don’t ask to play them, with the occasional exception of the E Minor (K. 304) or the big B-flat Sonata K. (K. 454).

All of this is to say that Kit Armstrong and Renaud Capuçon have their work cut out for them; there are many perfunctory performances of these scores. Luckily, the duo comes through with flying colors. The clarity of Armstrong’s scales, arpeggios, trills, Alberti bass, etc. is often startling. More importantly, he plays boldly, with much color, and his phrase shaping is always elegant. There are many telling details in his performances: a burbling left-hand line suddenly brought to the fore, a melodic line after scintillating passagework played with caressing warmth. One hopes that he will record the piano sonatas or concerti next. For his part, Capuçon seems to want to deny the secondary nature of the violin parts, to good effect. Like Armstrong, he plays with great vigor, but never allows his overwhelming energy to disrupt his flowing bow arm or buttery tone. (The latter would have pleased Mozart, who as a child referred to a visitor’s violin as a Buttergeige due to its sweet sound.)

Those new to the Mozart sonatas should have no fear of starting from the top and working their way through the set. The earlier sonatas are melodically fresh, rhythmically robust, and although they may not remain in the memory as easily as Mozart’s better-known music, they contain many intriguing moments. In an unexpected way, much of the music seems to be a sort of premonition of compositions to come, and not always by Mozart. The E Minor Sonata (K. 304) possesses a melancholy unison opening that quickly suggests the music of Schubert; this impression persists when hearing the repeated thick chords in the piano part (think the beginning of the D Major Piano Sonata D. 850 transplanted into Mozart’s sound world). The later sonatas begin to present rhythmically complex themes reminiscent of Beethoven; the opening of K. 526 begins on an offbeat that is further knocked off kilter as a result of the two-note bowings/phrase markings indicated by Mozart. (It is worth noting that the muscular energy brought to the music by Armstrong and Capuçon likely emphasize this similarity to Beethoven.)

The recording sound is excellent, and the balance between the instruments is roughly equivalent, exactly as it should be.

Richard Masters

Previous review by Stephen Greenbank (August 2023)

Help us financially by purchasing from

Contents:

Sonata No 17 in C major, K296

Sonata No 18 in G major, K301

Sonata No 19 in E-flat major, K302

Sonata No 20 in C major, K303

Sonata No 21 in E minor, K304

Sonata No 22 in A major, K305

Sonata No 23 in D major, K306

Sonata No 24 in F major, K376

Sonata No 25 in F major, K377

Sonata No 26 in B-flat major, K378

Sonata No 27 in G major, K379

Sonata No 28 in E-flat major, K380

Sonata No 32 in B-flat major, K454

Sonata No 33 in E-flat major, K481

Sonata No 35 in A major, K526

Sonata No 36 in F major, K547

Variations on ‘Helas, j’ai perdu mon amant’, K360/K374b

Variations in G major on ‘La Bergere Celimene’, K359 (K374a)