Gustav Mahler (1860-1911)

Symphony No. 5 in C-sharp minor

Symphony No. 7 in E Minor ‘Song of the Night’

Symphony No. 8 in E Flat Major ‘Symphony of a Thousand’

BBC Symphony Chorus & Orchestra/Sir Adrian Boult

rec. live radio broadcasts, 1947/48

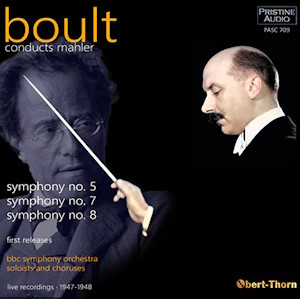

Pristine Classics PASC709 [3 CDs: 228]

If I were to ask you which conductor was responsible for the first recording, in the studio or otherwise, of Mahler’s symphony numbers 3,5,7 and 8, your first inclination might well be to think of Otto Klemperer or Bruno Walter – before then remembering that Klemperer did not conduct the Third, Fifth, or Eighth, nor Walter the Seventh and Eighth – and although he conducted the Third several times, he never recorded it (nor did he ever conduct the Sixth, as he found it too bleak). Perhaps Dimitri Mitropolous would be your next thought – he definitely conducted all of Mahler’s symphonies, but is not the answer. Nor would be Hans Rosbaud – his taped radio broadcasts with the WDR Orchestra of Baden from the mid-1950’s, do not include those symphonies with chorus, so numbers 2,3 and 8 are missing. If you then nominated John Barbirolli, you would be getting closer – but Glorious John did not start conducting Mahler until late in his career. However, if at that point I were to tell you that, actually, the answer was Sir Adrian Boult, you would be forgiven for being a little surprised.

That it is (almost – see below) Boult is something of a minor miracle. Of course, the dedicated Mahler collector would be aware of a rather fine (if not great) Mahler First that Boult recorded for Everest with the London PO in 1958, as well as his conducting of the orchestral songs of Kindertotenlieder, plus the Lieder eines fahren Gesellen for other labels on more than one occasion. However, he also took part in a rather unusual Mahler Symphony cycle for the BBC in 1947 and 1948. where studio recordings of The Resurrection (Ormandy/Minneapolis), the Fourth (Walter/NYPO) and Ninth (Walter/Vienna PO), were augmented by a radio broadcast of the First with Bruno Walter leading the London Philharmonic (wrongly attributed to the BBC SO in Pristine’s notes), and a German radio broadcast of the Sixth with Hans Schmidt-Isserstedt and the NDR Orchestra (broadcast on the evening of 31 December 1947 – one way of welcoming the New Year, I suppose); Boult and the BBC SO were entrusted with the remainder. At the time, the BBC did not make archival recordings of their broadcasts – instead what was captured for posterity was recorded from the home of a certain Edward Agate, a musicologist and translator of opera libretti, who took down every broadcast from this series (as well as much else) all captured on over two hundred acetate discs that somehow ended up in a random record shop in Manchester after his death. The miracle is that this collection was then spotted by the music writer, Jon Tolansky, who bought them all and thereafter donated them to the organization Music Preserved, the current owners of the discs, who have given permission for this release by Pristine, issued to commemorate the fortieth anniversary of the death of Sir Adrian Boult (1889-1983).

Of course, “home taped radio recordings of live performances from the 1940’s” is not a phrase to excite even the most dedicated collectors of historical recordings, all of whom would have experienced the pain of listening to the sounds of a full English with the frying pan furiously sizzling away, accompanied by vague sounds of music in the background, not least since the indefatigable Mr Agate also had to use a two-cutter setup to enable continuous recording. So not only did the original tapes contain a generous portion of snap, crackle and pop, but there were also gaps in the music, too. That the audiophile wizard at Pristine has not only somehow used his black magic to erase practically all of the background noise but has also, by using discretely patched and aged missing phrases from other recordings, managed to produce seamless whole performances, deserves much praise – you would be extremely hard-pressed to spot the corrections for the missing bars of music. Indeed, unless you are the most dedicated Blu-ray maven, with one exception right at the very end of the Eighth Symphony (which in light of the massed forces being used, is quite forgivable), what is presented on these discs is more than listenable.

That said, none of the above would be of any importance had the music-making not been worth preserving – and I am happy to say that, on the whole, it is. Most readers will already know that Testament released the Third Symphony from this series in 2008, a reading that was distinguished by a final movement where a certain honeyed warmth and restrained Elgarian nobility elevated the performance to a level that deserves the attention of every Mahler afficionado. That broadcast took place on 29 November 1947 and was performed like the others, in front of a (commendably quiet) studio audience whose presence can sometimes be detected throughout the series, with occasional applause retained as well. In this BBC cycle, after Walter’s Mahler Fourth was then broadcast on Friday 12th December, I was intrigued to note that the Fifth Symphony was then programmed for Saturday 20th and, curiously, it was the only time it was thought that a first half of music was also necessary. I mention this as it is the only time in all of Boult’s recorded Mahler when I felt that the music-making sounded slightly under-rehearsed, not least since the additional pieces were Busoni’s Berceuse élégiaque and Violin Concerto, hardly standard repertoire in the late 1940’s any more than they are today. As a result, I cannot help but wonder if too much time was taken away from the Mahler symphony when preparing for this concert. So the opening trumpet fanfare sounds rather cautious, an impression not improved when a few bars later after the cymbal clash, there is a jarring split note in the fortissimo orchestral chord (bar 14). After this is a performance where there are too many moments when the phrasing is slurred, the balances approximate and the ensemble uncertain. This is unfortunate, since Boult shapes the symphony well and is often able to generate considerable heat, especially during the more tumultuous moments in the first half, although when the clouds part in the middle of the second movement to reveal the promised lands of the finale, the harps are nowhere to be heard. Intriguingly, his Adagietto is a leisurely ten minutes and twenty seconds, which is notably slower than the flowing love songs that had gone before in recordings under Mengelberg and Walter, as well as the roughly contemporary Hans Rosbaud’s 1951 radio recording from Cologne – and Boult does it more passionately than you may have expected too. However, it is followed by a somewhat stodgy finale and as the symphony draws to a close with a rather weary plod to the finishing line, I have to register some disappointment, for this is below par for both Boult as well as other recorded performances of this symphony at the time, such as Walter/NYPO (studio, 1947), Kubélik/Concertgebouw (live,1951) and Rosbaud/Cologne RSO (radio broadcast/1951).

After the New Year’s Eve broadcast of the Sixth Symphony, Boult and his players returned at the end of January for this performance of the Seventh Symphony. Coming so soon after their somewhat underwhelming Fifth, I was astonished at how poised and intuitive they are in their execution of this score, in what is supposed to be Mahler’s most difficult and misunderstood symphony. Indeed, from the superb opening tenor horn solo onwards, this broadcast puts many modern recordings and ensembles to shame and by happy chance, is also the best sounding issue in the series – if you had told me that it was a radio broadcast from ten years later, I would have still been impressed, such is the clarity of detail with nicely prominent timpani and bass drum in the final movement too. My criticisms are few are far between, but include noting how the fanfares just before the religious vision episode in the first movement are somewhat declamatory, missing a sense of fantasy or mystery; how the orchestral skid down five octaves at the start of the first Nachtmusik is obliterated by the percussion; that the close of the second Nachtmusik is slightly brusque and matter of fact, while the opening measures of the final movement are too stodgy, as they are whenever they are subsequently repeated, a rare miscalculation on the part of the conductor. However, everything else is spot on – and often extremely good indeed. Of course, there is a touch of English reserve in the spooky central scherzo, but there is more character here than Bernard Haitink ever found with his super-refined and ultra-polite way with the music in this movement and the second Nachtmusik is a nicely flowing twelve minutes, that never sounds hurried until those aforementioned final bars. Best of all is the final movement that finds the BBC brass in imperious form, so much so that it is a slight disappointment that there is no audience applause retained at the end, replaced instead by a Boultian stiff-upper lipped BBC presenter who articulates the closing credits in a way that would make the British Royal Family proud. If in the ‘historical’ category of Mahler’s Seventh Symphony, this performance does not quite hit the heights of John Barbirolli’s live concert performance from 1960, nor matches the devil-may-care panache of van Beinum’s Concertgebouw live performance from 1958 (which, in any case, is in vastly inferior sound), then that is because few others do either; overall, though, this Mahler Seventh is an exceptional achievement.

Boult and his players are also the heroes in the next instalment of the cycle, the Eighth Symphony, barely two weeks later, switching from the BBC Maida Vale studios of the previous symphonies to London’s Royal Albert Hall – not only do they sound inspired in music that nobody in the massed forces assembled here could have been familiar with, but the orchestral parts are also executed superbly too, something that shines through in spite of the decent, if limited, sound and a wayward first soprano who habitually rushes ahead of the beat in Part I. Boult starts the great Latin hymn ‘Veni, Creator Spiritus’ excitingly and, aided by a surprisingly present organ in the opening bars, maintains the tension throughout the movement with swift tempos. Occasionally, orchestra-chorus coordination is just about hanging together by a thread and the balances can sometimes be a bit weird, not least in the leadup to the recapitulation with over-prominent organ and trombones, but as Boult broadens the tempo in final bars to bring the first part to a close with real grandeur, he is greeted by well-deserved and enthusiastic applause from the audience. Part II is, of course, very different and we get to hear more of the soloists too, all of which, with one exception, are very good indeed. If Elena Danieli is more disciplined here than in the first half, her tone and style is decidedly old-fashioned, even for the late 1940’s and is rarely pleasant- she is the one real blot on what would otherwise be a good performance, even if additional allowances also need to be made for the English text used in place of Goethe’s original German. Boult shapes the music with more rubato and affection than you might have given him credit for and, possibly/probably, much colour too, from what you can hear. He builds the final Chorus Mysticus with much skill as well and it is clear that he is inspiring his forces to storm the heavens, but unfortunately he is slightly let down by the sonics on the very final page of the score – if at the end of Part I the sound was just about all there, albeit straining the bandwith to all but bursting point, at the end of Part II all you can hear is the organ and timpani, with everything else drowned out including, critically, the offstage brass.

For those reading this who have witnessed the Royal Albert Hall organ in the flesh, it will come as no surprise to learn that such a mighty beast is both hero and villain in Boult’s performance, proud and present in Part I but overwhelming everything at the end of Part II. Eleven years later, the BBC engineers were more prepared when they broadcasted Jascha Horenstein’s LSO performance of the same work in the same hall at The Proms in 1959, so much so that Horenstein’s cautious tempos are often electrified by that organ’s entries which, in turn, lend an overwhelming grandeur to a reading that has been captured in astonishing sound for its time. From the same era, in comparison Leopold Stokowski’s live performance with the New York PO in 1951 has a Lilliputian organ that can be barely heard at all – but in compensation, all his soprano soloists are significantly better than Boult’s. Stokowski may not be renowned for his Mahler, but from all accounts he was present during the composer’s rehearsals for this symphony’s premiere in Munich, making notes into his own score that he deemed so valuable, he was prepared to risk much in returning to a Europe engulfed in war in 1914 to collect it, thus enabling him to present the symphony’s first performance in the USA with the Philadelphia Orchestra two years later. Stoki is never going to be anyone’s nomination for the go-to conductor to represent a composer’s true wishes, but on this occasion in 1951 he is on his best behaviour and even shows signs of significant insight and confidence with his interpretation, for example adopting a slightly more relaxed tempo after the opening choral salvoes of Part I when the soloists enter, which contrasts to Boult who remains strictly in a tempo. It is interesting to note as well, that whether influenced by seeing Mahler conduct the piece of not, Stokowski – like Boult – is overall both fast and fiery in Part I, unlike the steadier pulse adopted by Horenstein, as well as Eduard Flipse in his live recording from Rotterdam in 1954, featuring two orchestras and what must have been all the choruses in Holland. That recording, despite some distortion, manages to capture something of the tremendous sense of occasion of that one-off performance that did indeed have over a thousand performers and was presented as part of the Holland Mahler Festival that year and has remarkable grandeur, even if it lacks the white heat of both the Stokowski and Boult. All of these are better than Hermann Scherchen’s 1951 account live with the Vienna Symphony Orchestra, eccentrically conducted and in sound that requires the greatest tolerance. However, with its English text for the Faust-inspired second part, poor first soprano and its compromised sound at the end, I have to say that Boult’s is not ideal either, which means if you are able to secure a copy of the Stokowski recording from the New York Philharmonic’s ‘Mahler Broadcasts’ box, that performance is probably still the pick of the historic category of the Symphony of a Thousand.

If I am disappointed with the sound at the end of the Eighth Symphony, this is not to undermine what Pristine has achieved with this release and if any proof was required, a comparison at any point in this release with the Testament issue of the Third Symphony is instructive, not least since the latter has loud acetate noise running continuously throughout the performance. Even if Pristine can only do so much with the dynamic range that is a little compressed, with the soloists in the Eighth Symphony often sounding as loud as the massed choruses, the fact you can still hear so much detail, such as the mandolin for example, is something to marvel at – and in any case nobody should be investigating this issue for its (lack of) sonic glories. In this release, each symphony is contained on a single disc, presented in cardboard slipcases and the Eighth Symphony has twenty index points. Notes are restricted to the provenance of the performances and the sonic wonders needed to restore them to life, rather than anything to do with Mahler or the symphonies themselves, reinforcing that this is a release for the specialist, rather than general collector or audiophile.

At the beginning of this review, I posed a question and gave Boult as being the answer – so forgive me if I now have to disclose that I was not being wholly truthful with the facts, since Bruno Walter had recorded the Fifth Symphony earlier in 1947 with the NYPO. However, at the time of the BBC cycle, that recording had not been released yet, which is why Boult and his BBC forces were called into action for the broadcast performance. Similarly, it has long been assumed that Hans Rosbaud’s recording of the Mahler Seventh with the Berlin Radio Symphony Orchestra was set down in 1953 (it is still listed as such on the Mahler Foundation Discography), but recent archival evidence (including newspaper reviews) shows that Rosbaud conducted the work at Berlin with its radio orchestra in concert on 11 January 1948 and did not programme the same piece again until after 1953 – which verifies the earlier date of the performance and means he too pipped Boult to the first-past-the-post in the Seventh Symphony by a couple of weeks. However, I am sure everyone appreciates the point I was trying to make. Either way, this is not to take away anything from what Pristine is presenting to us – Sir Adrian Boult in repertoire that he is not associated with in dedicatedly restored recordings. I cannot think of a better way to honour the fortieth anniversary of this conductor’s death, nor the legacy of Edward Agate, to whom we now all owe so much.

Lee Denham

Availability: Pristine Classical

Details

Symphony No 5

Broadcast of 20 December 1947 from BBC Maida Vale Studio No. 1, London [72]

Symphony No 7

Broadcast of 31 January 1948 from BBC Maida Vale Studio No. 1, London [78]

Symphony No 8

Broadcast of 10 February 1948 from the Royal Albert Hall, London [79]

Magna Peccatrix – Elena Danieli (soprano)

Una Poenitentium – Dora van Doorn (soprano)

Mater Gloriosa – Emelie Hooke (soprano)

Mulier Samaritana – Mary Jarred (contralto)

Maria Aegyptiaca – Gladys Ripley (contralto)

Doctor Marianus – William Herbert (tenor)

Pater Ecstaticus – George Pizzey (baritone)

Pater Profundus – Harold Williams (bass)

BBC Choral Society (Leslie Woodgate, chorus master)

Luton Choral Society (Arthur E. Davies, chorus master)

Wallington Choral Society (Robert Noble, chorus master)

Watford and District Philharmonic Society (Leslie Regan, chorus master )

Lambeth Schools’ Music Association Boys’ Choir (Francis Steptoe, chorus master )

Boys of Marylebone Grammar School (D. H. Hedges, chorus master)