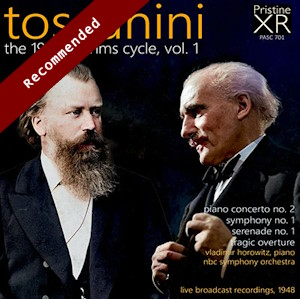

Johannes Brahms (1833-1897)

Serenade no. 1 in D major, op.11 – I. Allegro molto

Piano Concerto no. 2 in B flat major, op. 83

Tragic Overture, op. 81

Symphony no. 1 in C minor, op. 68

Vladimir Horowitz (piano)

NBC Symphony Orchestra/Arturo Toscanini

rec. Studio 8H, NBC Radio City New York, 23 October 1948 (Serenade and Concerto), 30 October 1948 (Overture and Symphony)

Includes Introductions & Conclusions to Brahms Cycle Programmes 1 & 2

Toscanini: The 1948 Brahms cycle Volume 1

Pristine Audio PASC701 [2 CDs: 118]

These historic recordings of concerts in Toscanini’s 1948 Brahms series with the NBC Symphony Orchestra were first published on CD in 2007, on the label Pristine Classical. As Andrew Rose, responsible for those issues and also this new one, explains in his note, fresh sources of these takes of live concerts in NBC Studio 8H have since become available to him, and he clearly feels that the quality of these updates to be far superior. I can’t comment, as I have not heard the earlier pressings; but there is no doubt that the sound on these new issues is, considering their age, absolutely stunning.

I very much like that the introducing and concluding radio announcements have been kept, so that the whole thing has a truly ‘live’ feel to it. The audiences are highly demonstrative, with rousing cheers at the ends of the big works. In one or two places, there is some distracting extraneous noise – coughing mostly – but it is emphatically not enough to mar these stupendous performances. By this time, Toscanini was at the height of his powers, and had built the NBC SO into a formidable musical force.

Of course his monumental tantrums and occasional victimisation of individual players became legendary, and there’s no doubt that players were wary of him. In his American years, some of that was no doubt brought about by frustration because of his sketchy knowledge of English. For many people, however, all of that was at least partially justified by the sheer brilliance of the performances he achieved, and these CDs bear that out convincingly.

After the station announcement, CD1 begins, rather surprisingly, with the first movement only of Brahms’s Serenade no. 1, Allegro molto, used as an overture. It’s a fine movement, although the opening is one of the few unsatisfactory moments in these recordings; the horn solo is indistinct and a little insecure too. Perhaps the player was not quite prepared for Toscanini’s very literal response to the ‘molto’ part of Brahms’s tempo indication – it really is very quick! But Toscanini liked fast speeds, and, as usual, this gives the music a tremendous sense of energy and impetus.

But the real meat comes next, a monumental performance of the second Piano Concerto, with Vladimir Horowitz at the keyboard. I love this concerto so very much, and I don’t think I have ever heard such a compelling overall performance on disc. Given the date, one has to say that the balance between solo and orchestra is outstandingly good; Horowitz projects the solo part with a mixture of bravura and lyricism, and Toscanini and his players respond in kind. The slow movement is mesmerising, with utterly beautiful solos from the principal ‘cellist all the way through (a pity the player is not credited, but is almost certainly Frank Miller, who played for Toscanini for fifteen years, and went on to lead sections for Reiner and Solti in Chicago). Horowitz employs the most hushed pianissimo in places; annoyingly, there are one or two volleys of coughing – must have been a cold October in New York! – which even modern technology cannot entirely banish. The whole movement is a beautiful dream, from which the Allegretto finale gently awakens us.

The second disc contains, like the first, just two works; the Tragic Overture and Symphony no. 1. The overture is, again, brisk, so that some of the quieter music feels rushed. Yet overall, this is a powerful performance, and, as so often with Toscanini, his possession of a total mental image of the work’s totality finally brushes aside – for me anyway – any reservations.

All of that applies to the symphony, even more so as we are now on a far larger scale. There is a most interesting interview available online with Sir Adrian Boult, who discusses his experiences of Toscanini when he came over in the 1930s to work with the BBC Symphony Orchestra, of whom Boult was the chief conductor of the time. Asked about Toscanini’s most important quality as a musician, Boult unhesitatingly identified his powers of concentration, which enabled him to draw exceptional playing from his orchestras, and was also responsible for his sure sense of the direction and structure of the music he was conducting.

He recorded all the Brahms symphonies in the studio a couple of years after these concerts, and the November 1951 recording on RCA is the version of this work that I first got to know, as a schoolboy in the ‘60s. It overwhelmed me then, and this performance has the same intensity that is possessed by that studio version. Yes, some of the woodwind playing is less than subtle; but Toscanini was determined that, in addition to important solos, significant details, with which Brahms’s music teems, should always be clearly heard.

The opening of the first movement sets out Toscanini’s approach immediately; no holds barred. The drums thump inexorably, the opposing lines, strings up, woodwinds down, diverge agonisingly. The Allegro that follows has such drive, such menace. Listen to the savage entry of the violas with that three-note motif – track 3, 4:40 – or the raging storm that Toscanini whips up in the coda of the same movement.

The defining passage of the whole symphony is the finale’s transition from the haunted, terrified introduction to the great Allegro non troppo. Here Toscanini shows his ability to characterise the music so strongly, with glorious horn and flute solos giving way to a broad, confident singing of the great anthem that dominates the Allegro.

This issue is more than ‘historic’; it is a valuable correction to our sometimes ‘safety first’ approach to music-making these days. We can sometimes be guilty of expecting everything to be ‘correct’ and ‘satisfactory’, words that weren’t in Toscanini’s musical vocabulary! Perhaps I wouldn’t want to listen to these recordings every day – it would be too emotionally exhausting. But every single one is an experience of a real event, and the ecstatic response of the audiences confirms that they all knew they were in the presence of greatness.

Gwyn Parry-Jones

Availability: Pristine Classical